It’s coming up to mid August on Elba, and the entire population of Tuscany, or so it seems, has decanted itself on to this tiny Mediterranean island six miles from the Italian mainland. As the 15th of the month approaches, it’s increasingly hard to see any sand on the beaches for lime-green speedos and inflatables of equally garish colours. Italy’s public holiday of Ferragosto has its roots in the feriae Augusti, introduced by Augustus in 18 BC as a day of rest and celebration after the summer’s intensive harvest period. The Catholic church later earmarked the date for the Assumption, making it a holy day of obligation; but it was Mussolini, ever keen to associate himself with the first Roman emperor, who made this particular national holiday the seaside jolly it is today. The fascist leader laid on trains at discounted prices for the days around Ferragosto, allowing those of limited financial means to escape the city heat for the country’s coasts.

This date, 15 August, has traditionally been a double celebration for Elba, however, it being the birthday of the island’s most famous one-time resident, Napoleon Bonaparte (who had Tuscan ancestors). His image, and his emblems of the eagle and the bee, crop up all over the island, perhaps most conspicuously on its flag, designed by the man himself: a white ground with three golden bees on a red diagonal stripe. At dusk in the medieval hill town of Marciana, teenagers smoke cigarettes illicitly by the 16th-century church of Santa Caterina – away from parental eyes, but watched over by the bicorn-sporting general in fresco form on the wall opposite.

In the gelateria around the corner I pick up a copy of the Corriere Elbano. On its front page, Paul Delaroche’s portrait of a paunchy, petulant-looking Bonaparte at Fontainebleau makes an appropriate illustration for the headline ‘Niente Festa di Compleanno’ (No Birthday Party); there are no significant events planned, so the article complains, for two big anniversaries this year: the 500th birthday of Cosimo I de’ Medici, founder of Elba’s main harbour town, Portoferraio, and the 250th anniversary of Napoleon’s birth.

Napoleon at Fontainebleau, 31 March 1814 (1840), Paul Delaroche. Musée de l’armée/Alamy Stock Photo

Delaroche is thought to have based his portrait of 1840 on a description in the Baron de Norvins’ Histoire de Napoleon (1828) of the emperor at Fontainebleau on 31 March 1814, just after Paris capitulated to the invading Allied armies. The painting’s morose mood was no artistic licence – some days later, having signed the Treaty of Fontainebleau (effecting his abdication and exile to Elba), Napoleon attempted suicide. The poison that had hung around his neck since his near-capture in Russia had, however, lost its potency, and face exile as ‘Sovereign of Elba’ he must. ‘Ah well, my son, prepare your cart,’ he told his valet; ‘we will go and plant our cabbages.’ Escorted by Allied commissioners, he arrived on Elba – within sight of his native Corsica – on 3 May 1814.

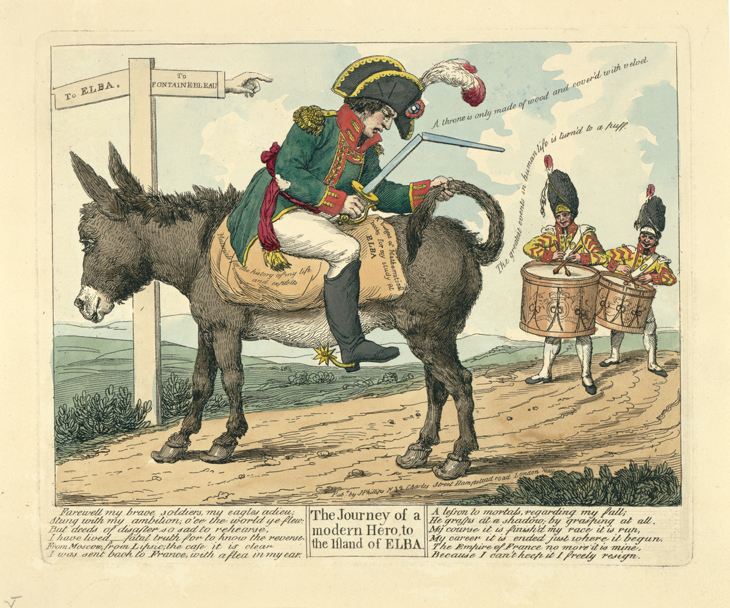

The journey of a modern hero, to the island of Elba (1814), artist unknown, published by J. Phillips. National Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

‘Able was I ere I saw Elba,’ goes the palindrome mischievously attributed to him. But in fact the Frenchman’s incorrigible competence found ample expression, even in his vastly reduced empire of 11,400 islanders. In the nine months he spent on Elba before escaping back to mainland France, Napoleon had a hospital built, improved the island’s defences, its customs and excise, and the production of its iron mines, repaired the barracks, organised a rubbish-collection system, and planted not cabbages but acres of vineyards and mulberry trees.

For his main residence, Napoleon chose the Palazzina dei Mulini in Portoferraio, built in 1724 by the Grand Duke Gian Gastone de’ Medici. To this he made alterations, including the addition of a ballroom, and installed a library of books brought with him from Fontainebleau (these are still at the house, which is now a museum). Meanwhile the Villa di San Martino, 5km out of town, served as his more private ‘summer residence’. Today a long avenue brings visitors through grand, eagle-topped iron gates to a neoclassical stone facade decorated with bees and ‘N’s. So far, so predictably palatial. Except that this isn’t Napoleonic in the truest sense at all, but a later addition designed by the architect Niccolò Matas and commissioned as a monument to Napoleon by the diplomat and art collector Anatole Demidoff, whose fandom even extended to marrying Napoleon’s niece. The building serves as a rather cavernous exhibition space for a collection of Napoleon-related engravings.

The Villa di San Martino, Elba. Photo: Mihael Grmek/Wikimedia Commons (used under Creative Commons licence [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Lying hidden behind this colossus, the relatively humble original villa houses a series of rooms now reinstalled with Empire-style furniture to evoke Napoleon’s time there. But the most delightful elements here are original, namely the different decorative schemes in each room. The most ambitious of these is a central hall painted with trompe-l’oeil Egyptian columns, hieroglyphics and vistas, perhaps drawn from the illustrations being made at the time for Napoleon’s vastly costly Description de l’Égypte. They were done by one Vincenzo Antonio Revelli from Turin, who in other rooms painted faux coffered ceilings stamped with golden bees and Légion d’honneur stars, or pearls and laurel wreaths. A dedicated Council room bears trompe-l’oeil drapery around the walls, and on the ceiling a painted ‘stretched’ canopy with a pair of doves at the centre, clasping a knotted blue ribbon in their beaks – thought to represent Napoleon and his estranged Habsburg wife Marie Louise.

The Egyptian Room at the Villa di San Martino, Elba Photo: the author

The colour scheme is surprisingly delicate and fresh for a man who all the while, surely, had his sights set on a military comeback (did his sister Pauline, who kept him company on Elba, have something to do with the decoration here?). Pastel pinks and pale yellows abound, complemented charmingly by pistachio greens – with not an arsenic-laced emerald hue in sight.

From the October 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze