Man Ray was a reluctant photographer. His career behind the camera was cash-driven and he famously claimed that ‘photography is not art’. And yet, in Paris, between 1920 and 1940, the young American expat turned his lens to the fashion industry in a way no one had done before. He paid attention to the elongated models, the way they held themselves and moved in the clothes. He toyed with lighting, proportions, perspective, and enriched images with his Surrealist themes and bold new methods. A touring exhibition currently at the Musée du Luxembourg – which is divided into four chronological sections and displays more than 200 prints of the artist’s black-and-white images alongside magazines, haute couture and film clips – explores how fashion informed his work and how he in turn influenced the industry.

Man Ray was born Emmanuel Radnitzky in 1890, to a Russian immigrant family in Philadelphia; his mother made clothes and his father worked in a garment factory. (Perhaps it should come as no surprise, then, that he flirted with the world of fashion.) As a young art student in New York he was introduced to Dada and Marcel Duchamp – whom he followed to the French capital in 1921. Man Ray was accustomed to photographing his own art and in Paris he snapped the work of his Surrealist pals to boost his income. He also developed a habit of turning his lens on each artist at the end of a shoot – and so began his foray into commercial portraiture. Where the artistic avant-garde went, society figures followed, and he soon found himself shooting worldly women for whom the wearing of haute couture was integral to their social standing. It was while photographing these private clients, from the Countess Edith de Beaumont to the Egyptian beauty Nimet Eloui Bey, that he subtly shifted his attention to fashion. Encouraged by the couturier Paul Poiret, he began to shoot for magazines. He abandoned his formal compositions and instead focused on capturing feminine silhouettes, fantastical clothes and a dreamlike sense of glamour.

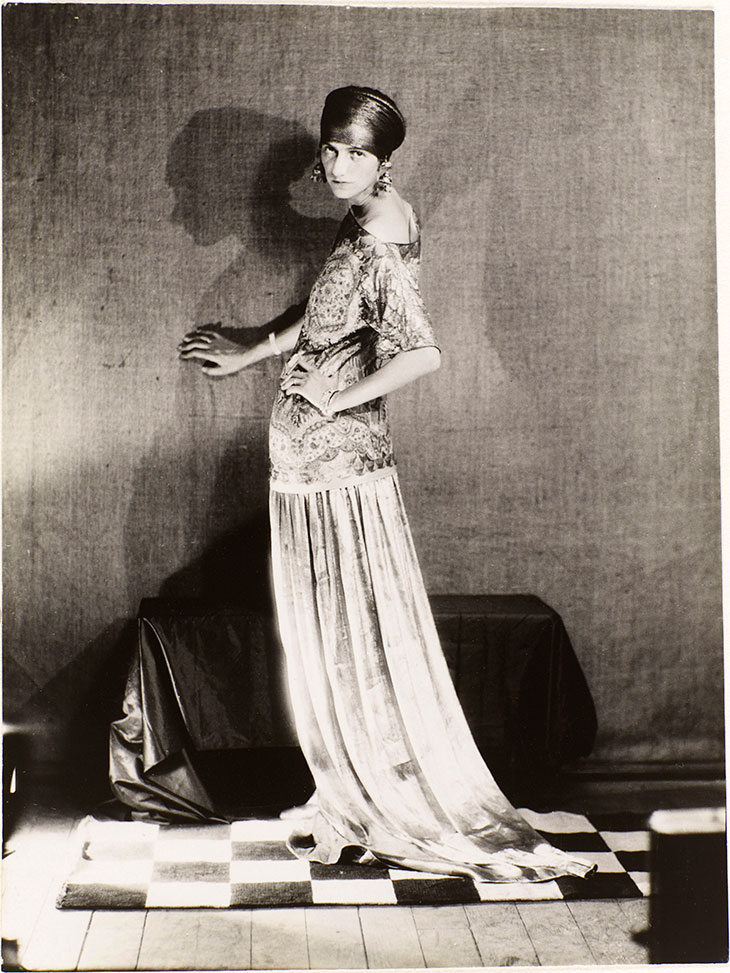

Peggy Guggenheim dans un robe de Poiret (1924), Man Ray. Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, dist. Rmn-Grand Palais/Guy Carrard; © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Adagp, Paris 2020

At the Musée du Luxembourg, two full-length portraits show Peggy Guggenheim in a Poiret gown, her satin tunic and gold lamé skirt glistening in the light before an almost-black backdrop. Man Ray captured on camera the height of the Roaring Twenties. The outré characters, too: a double portrait taken at the Beaumonts’ masked ball in 1924 shows the heiress Nancy Cunard leaning against a pillar dressed as a man and her partner, the high priest of Dada Tristan Tzara, kneeling and kissing her hand. These images are interspersed with a medley of the haute-couture items photographed by Man Ray. A pair of cream-coloured Coco Chanel evening dresses typify the early-1920s trend for loose, lightweight fabrics, while an Elsa Schiaparelli black woollen coat with pink velvet pockets sewn on with golden thread shows ornamentation enjoying a comeback in the late 1930s.

As the fashions changed, so did Man Ray’s photographs – which from 1924–28 featured regularly in Vogue. Women became walking sculptures in long, fitted dresses inspired by classical antiquity and the artist further merged femininity and art in his work. Noire et blanche (1926) shows Alice Prin, otherwise known as Kiki de Montparnasse, posing with a ceremonial mask from the Ivory Coast. Man Ray had long been captivated by non-Western art and here he compares its allure to that of the celebrated model by capturing a likeness between the two oval faces, with their pursed lips and heavy lids.

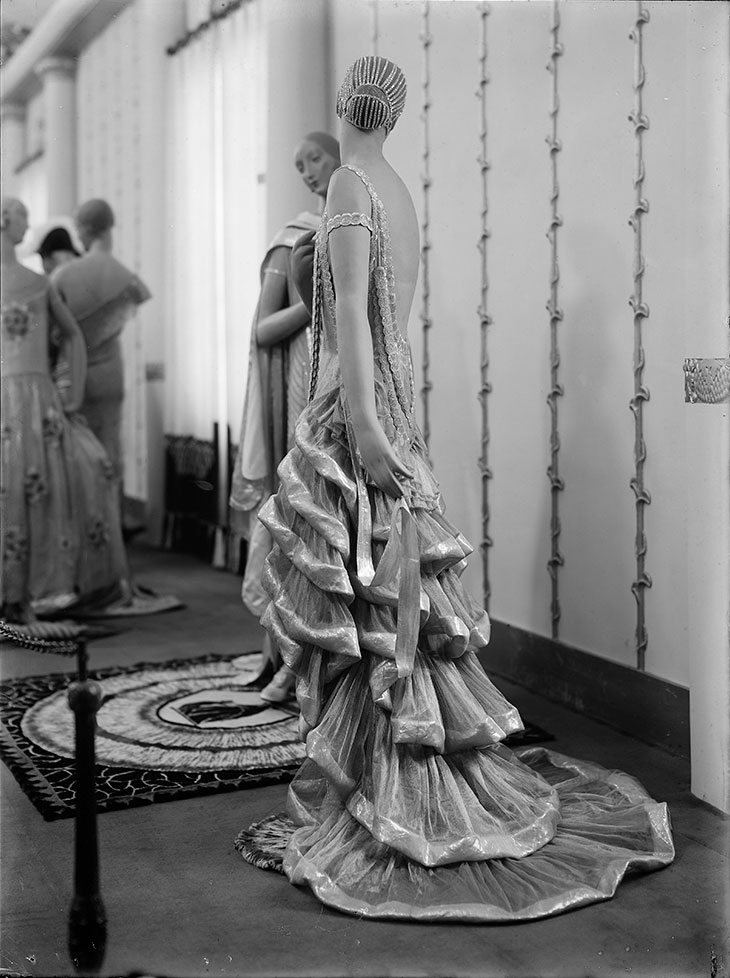

‘Apollo’ evening gown designed by Jeanne Lanvin, modelled on a mannequin at the Pavillon de l’Élegance of the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels, photographed by Man Ray in 1925. Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, dist. RMN-Grand Palais/image Centre Pompidou; © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Adagp, Paris 2020

In Man Ray’s hands, fashion photography was no longer about reproducing reality; instead, it was a way of exploring Surrealist themes, which crop up across the exhibition in the form of curious pairings, dramatic lighting, double exposures and illusory imagery. The eerie shots he took in the Pavillon de l’Élégance at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes concentrate on the uncanny mannequins made by André Vigneau, their hair and glass eyes curiously human. No surprise that they were later reproduced in the Surrealist journal Minotaure.

Some works openly promote the aesthetics of Surrealism – take En pleine occultation de vénus (c. 1930), which juxtaposes the head of a classical statue with the scroll of a violin and a sculptural pear on a plinth. Others, such as the shrewdly named Photographie publicitaire (1925), which shows a slender foot in a high-heeled shoe stepping onto a tiny ladder, deliberately blur the line between advertising and fine art by skewing the proportions. When detached from its commercial context, Les larmes (1932) – a tightly cropped image of a mannequin with long lashes and glass tears that was originally created as an ad for Cosmécil mascara – remains a powerful and memorable image in its own right.

During the time he spent working for Harper’s Bazaar between 1934 and 1939, surely keen to publicise his artistic prowess, Man Ray became even more daring. He experimented with innovative techniques such as solarisation, a process that involved exposing negatives to light in the darkroom; he mastered it together with Lee Miller, his assistant at the time, who prematurely switched on the lights while helping him develop some film one day. Sans titre (c. 1935) superimposes two images of a young woman twirling in a transparent dress blooming with flowers, giving the final picture a sense of movement; overexposure, in this photograph and elsewhere, is used to ramp up the contrast between light and dark. In Modèle dans une robe de Madeleine Vionnet dans une brouette d’Oscar Dominguez (1937) he adopts a bird’s-eye view characteristic of modern photography to highlight Sonia Colmer’s languid pose as, dressed in a pleated silver gown, she lounges in a wheelbarrow upholstered in pink satin.

Evening dress in printed black crepe, Elsa Schiaparelli, February 1936 collection n ° 104 (1936), Man Ray. Published in Harper’s Bazaar, March 1936. Palais Galliera, Musée de la Mode de la Ville de Paris. Photo: © Galliera/Parisienne de Photographie; © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Adagp, Paris 2020

In 1939, Man Ray left Paris for Los Angeles and gradually abandoned the medium that had made him famous. He returned to painting and maintained that he’d merely dabbled in photography, though occasionally he’d revisit it in the form of hybrid portraits: a picture of his soon-to-be wife Juliet, taken in around 1945, has been scratched over to the point that she looks like a cut-out paper doll. What the exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg shows, though, is that Man Ray’s photos were in fact hybrids from the start. They’re as much about the setting, the model, the lighting as they are about the clothes. These are images of desire, drama, dreams, and they were taken by Man Ray the fashion photographer – and artist.

‘Man Ray and Fashion’ is at the Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, until 17 January 2021.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)