From the April 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

On 28 May 1672, in the early days of the Third Anglo-Dutch War, a joint English and French fleet was moored off Southwold in Suffolk when it was surprised by 75 Dutch warships. Among those present at the Battle of Solebay were the Duke of York – the brother of Charles II, Lord High Admiral of the Fleet and future James II – and, on the Dutch side, the artist Willem van de Velde the Elder, who sat in a small boat on the edge of the smoke and flames busily sketching.

Within a year, Van de Velde (1611–93) was domiciled in England along with his son and painting partner Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633–1707). War had brought about the collapse of the Dutch economy and the Van de Veldes had been enticed to England by the King’s offer of a stipend of £100 each – and a further £50 from the Duke of York – and a studio in the Queen’s House at Greenwich. The sum was the same amount Charles paid to a fellow countryman, his Principal Painter, Peter Lely.

The Van de Veldes’ first major commission was a rude introduction to their new home: they were asked to design a set of cartoons for six tapestries depicting the Battle of Solebay as a de facto English victory rather than the reality – a bloody but inconclusive encounter that amounted to a winning draw for the Dutch. They had to swallow any national pride: business trumped patriotism. Only one of the hangings now survives and it is the centrepiece of ‘The Van de Veldes: Greenwich, Art and the Sea’, a thoroughly stimulating exhibition running at the Queen’s House at the National Maritime Museum to mark the 350th anniversary of the pair’s arrival in England.

The Burning of the Royal James at the Battle of Solebay, 28 May 1672 (1672), designed by Willem Van de Velde the Elder, made by Thomas Poyntz. Photo: © National Maritime Museum, London

Famous across Europe, the Van de Veldes were a prize for Charles II: when Cosimo III de’ Medici visited Amsterdam in 1667, he sought out just two artists – Rembrandt and Van de Velde the Elder. But the value Charles placed on them reflected not just the lustre of their names but the importance the Stuarts attached to seafaring. They saw Solebay as their Armada moment and wanted it memorialised as such by the most accomplished marine artists of the age. The message was straightforward: under the restored monarchy, England, master of the seas in both battle and trade, would be great again.

The Burning of the ‘Royal James’ at the Battle of Solebay, 28 May 1672 (1672), Willem van de Velde the Younger. Photo: © National Maritime Museum, London

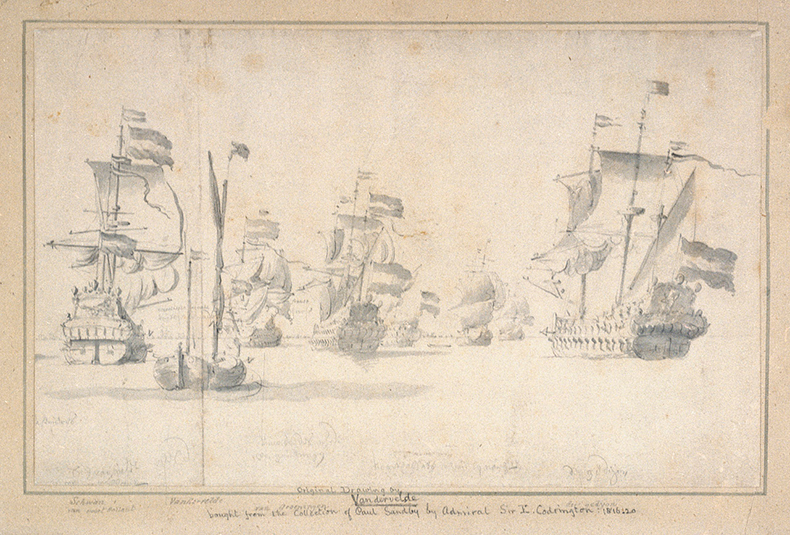

The exhibition, evocatively held in the building in which the Van de Veldes worked for much of their careers, includes not just the Solebay tapestry but Willem the Elder’s sketch made during the encounter of the burning of the ship Royal James, as well as the painting developed from it by his son. The grouping nicely encapsulates the way they worked: father sketched out on the water, son turned the drawings into paintings in the studio. The show also includes two other drawings of the battle, in one of which the elder Willem depicted himself as a war reporter at work. It was a perilous business and he noted with a degree of understatement that: ‘My galliot [a small merchant ship] had difficulty getting out of the way.’ And there is a diagram too of the battle as things stood at ‘two after none [noon]’, made by the Duke of York with the ships’ names annotated by Willem the Elder – an extraordinary record of collaboration.

Over the next 20 years the Van de Veldes produced a stream of vivid maritime works for their royal masters. It was, ironically, William III, another Dutchman, who ended their sojourn at Greenwich when he and his consort Mary became joint sovereigns. Father and son then took their business upriver to private patrons in central London.

The National Maritime Museum holds 1,400 Van de Velde drawings; 35 of them are hung here alongside 40 paintings to give an account of both their abilities and their practice. The pictures are handsomely dispersed throughout the Queen’s House, augmented by assorted nauticalia – carvings, scale-model ships and works by other marine painters.

The hanging makes clear how intertwined the Van de Veldes were with the monarchy they served. Both men had been among the crowds on the beach at Scheveningen in 1660: ‘Never had more people been seen together in Holland,’ said a contemporary – to witness Charles II’s embarkation to England after nine years in exile. Willem the Elder was on board the boat that carried Prince William and Princess Mary back to Holland after their marriage in Whitehall in 1677, and Willem the Younger was at Gravesend in 1689 to witness the return of Mary from Holland to join her husband and take up the English crown. The painters were both witnesses to and recorders of key moments in royal history.

The ‘Resolution’ in a Gale (c. 1678), Willem van de Velde the Younger. National Maritime Museum, London

There is necessarily a degree of repetition in the pictures on show, a shuffling of ships with magnificently carved sterns at anchor or firing cannon in battle or running under lowering skies and toppling waves – while the Dutch preferred paintings of calm seas, the English liked theirs stormy. Individually, however, the pictures show both how refined were the skills of each man and the transformation that happened when they pooled their complementary abilities.

Willem the Elder’s gifts are nowhere better seen than in a series of penschilderijen – large pen-and-ink drawings on canvas laboriously prepared with a white ground – which mimic oversized etchings and in which sailors, ships, rigging and the staffage of ports are rendered in mesmerising miniaturist detail. His son’s great ability was to enlarge and aggrandise his father’s rapid sketches, so that these often cursory notations became full-fledged paintings, executed with fijnschilder finesse. Willem the Younger’s most bravura work, A Royal Visit to the Fleet in the Thames Estuary, 1672 (c. 1674–c. 94), fully three metres wide, commemorates the occasion of Charles II boarding his brother’s flagship for a council of war. Every inch is alive with incident – scudding clouds, agitated water and teeming ships.

A Royal Visit to the Fleet in the Thames Estuary, 1672 (c. 1674–c. 94), Willem Van de Velde the Younger. © National Maritime Museum, London

It was paintings such as these that started England’s own tradition of maritime art, a point explicitly acknowledged by J.M.W. Turner when he said of a Van de Velde sea-piece: ‘This made me a painter.’

‘The Van de Veldes: Greenwich, Art and the Sea’ is at the Queen’s House, London, until 14 January 2024.

From the April 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)