From the February 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Even after decades of collecting Chinese antiquities and early 20th-century photography at the very highest level, and despite coming from a family of connoisseurs, Michael Feng confides, some time into our interview at his apartment in Manhattan, that he had been ‘so apprehensive’ beforehand. He had wondered whether there was enough art in his collection for Apollo to feature. He had no reason to worry; I could easily devote this piece to just one of his treasures in bronze, jade or turquoise, or to one of his thousands of paintings and photographs depicting figures, including his own ancestors, posing in tumultuous times.

A bronze Han dynasty horse, cast about 2,000 years ago, rears in the dining room overlooking Central Park. Its forelock and nostrils are flared, one hoof is raised and, as Michael says, its ‘mouth’s agape, ears are perked, tail’s flying – he looks like he’s ready to take off.’ Its posture resembles few others of its contemporaries: ‘Most are static, looking like farm horses, standing on all four legs,’ he adds.

A bronze Han dynasty horse stands in the middle of the dining room with a 17th-century woven silk depicting a pheasant on a branch (left) and an 18th-century painting of a falcon by Giuseppe Castiglione (right). Photo: Blaine Davis

With a little black flashlight, Michael shows me the faint lines of the joints between the nine sections of the creature’s original casting moulds – a tiny nail hole is visible along one haunch. Ghosts of harness straps can be seen in the crusty patina of the torso. As I walk around the sculpture, Michael points out bands of delicate feathering incised along the eyes and flakes of cinnabar pigment surviving inside the ears and mouth.

After a 40-year career on Wall Street, Michael Feng is now a private-equity investor specialising in health care. He has been building his collection for 30 years in consultation with his wife Winnie, a philanthropist, schoolteacher, librarian and archivist who has earned degrees in nursing and information science. The couple have served on the boards and committees of numerous institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Michael recently joined Christie’s Americas Advisory Board, and Winnie focuses on women’s empowerment as a trustee at the Asia Foun- dation. Michael and Winnie acquired the bronze horse two decades ago from a private collection in Beijing, when they made one of their first trips to China.

They are both descendants of Chinese immigrants, and many members of Michael’s family had been driven out of China by the Communist takeover in 1949. His paternal grandfather Kenneth Feng (a descendant of a tutor to the Qianlong emperor) served as an ambassador for Chiang-Kai shek’s Nationalist government before the Communists took power. Michael’s maternal grandfather T.V. Soong, who served as Chinese premier before 1949, helped found the United Nations and negotiated with Stalin. One of Michael’s great-aunts, May-ling Soong, married Chiang Kai-shek, became a political force in her own right and ended up in Taiwan and then New York. Another great-aunt, Ching-ling Soong, married Sun Yat-sen and stayed in Communist China, where she was celebrated as a stateswoman and bitterly estranged from relatives in the West.

There is no clutter in the Fengs’ home, where customised cabinetry and lighting were installed for the collection a decade ago. Shelves around the dining table are dedicated to archaic bronze vessels, which originally held foodstuffs or water for rituals. The surfaces of these vessels teem with tigers, dragons and phoenixes and are flecked with gold and iridescent mineral deposits. In the couple’s sunny bedroom, a 14th-century gilded Guanyin is relaxing in a wall niche. ‘It was built for her,’ Winnie explains, then points above the bed to one remaining expanse of blank wall, which awaits the couple’s choice of just the right artwork that will tolerate the light.

Over green tea, the Fengs and I discuss the traditions and innovations of different dynasties and the couple’s own changing acquisition habits. Winnie says that Michael is the main driver of the collection. ‘Every piece is “the last piece”,’ she says, ‘but then something else great comes up and you have to be ready to grab the opportunity.’ They originally focused on Chinese scroll paintings, but prices soared as mainland Chinese tycoons entered the market. The Fengs then embraced an increasingly multimedia, multicultural range of artworks, which echo and complement each other. Tina Zonars, co-chair of Asian Art at Christie’s, describes the Fengs as ‘true connoisseurs: passionate, knowledgeable, insightful, and discreet’. She praises the collection which has been gathered with ‘an unwavering eye for quality and condition as well as a disciplined approach to provenance.’

The Fengs have hung a black woodcarving by the contemporary artist Xu Bing, which represents the word ‘monkey’ in Korean, next to an Edo-period scroll paint- ing of a gibbon grasping at the reflection of the moon in a pool. (Michael and Winnie were both born in a monkey year, according to the Chinese zodiac.) In the painting – acquired at a Christie’s auction of the estate of the Asian art dealer Robert Ellsworth – the gibbon dangles from spindly tree branches. These in turn play off the snow- laden pine needles in a nearby photograph by Ansel Adams from the 1930s. And in a photo from 1926 by André Kertész (bought at the recent Paul Allen sale), the crosshatchings of a cello’s bow and strings recall the Han royal inventory markings etched into the rim of a jade rhinoceros. (The latter once belonged to the Hong Kong philanthropist and collector Joseph Hotung.)

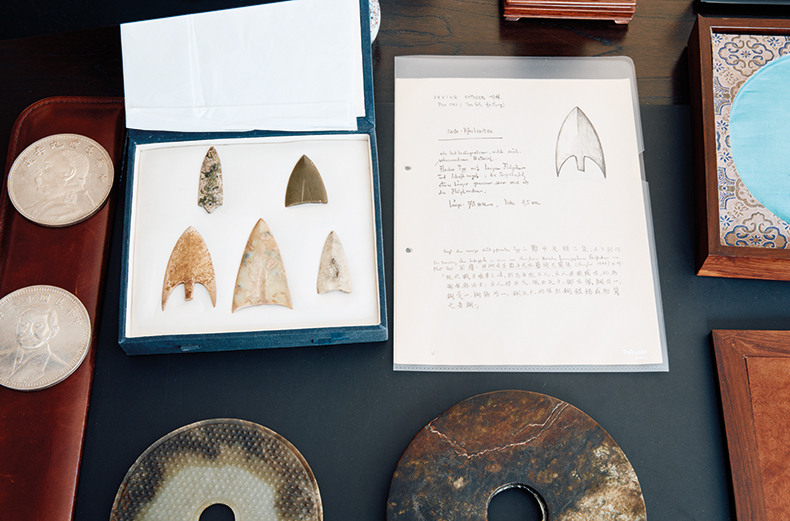

Five stone arrowheads from the Shang dynasty that were once in the collection of the art historian Max Loehr (1903–88), with the scholar’s notes. Photo: Blaine Davis

These visual connections reflect Michael’s view that ‘All art is related – it’s about light and form.’ Bringing out a recent arrival of five jade arrowheads fitted into a silk box, he adds, ‘I’m a stickler for documentation and provenance.’ They came with the German scholar Max Loehr’s sketches and handwritten notations about their contours and provenance. Loehr had acquired the pieces in the 1940s at a store in Beijing and then brought them westward, after Chinese Communists forced him out of his scholarly posts.

Michael shines a flashlight on the lids and underbellies of his bronze vessels and lets me feel their heft. He points out the chemical interaction of minerals in the earth with ancient buried bronze, forming shimmery dots of cuprite, malachite and azurite. He shows me custom- made padded fabric boxes for his jades and explains how Neolithic artisans drilled and abraded chunks of jade into buttery smooth ornaments designed to be hung from belts on elite clothing.

On the bases of the jades and bronzes, there are labels from past connoisseurial owners, such as Giuseppe Eske- nazi and Carl Kempe, and from being shown in museums. Michael brings out exhibition catalogues and other schol- arly tomes in which the objects are illustrated and their cross-continental journeys mapped over the centuries. Scholarship keeps changing, Michael notes. A turquoise mosaic plaque, made about 3,700 years ago, was long thought to have served as part of a horse’s burial regalia, but it may actually have been worn on the arm of a shaman.

Winnie scrolls through her phone to bring up a photograph of Jackie Kennedy visiting Cambodia in 1967, around the time that the former First Lady received an armless sandstone carving of the goddess Uma as a gift from Prince Norodom Sihanouk. The sculpture now occupies a window niche in the Feng’s library. ‘It brings a lot of joy and serenity to our lives,’ Michael says.

The core ingredients for any collection, according to Michael, can be summed up in the acronym PORK. ‘P is for passion; O is for opportunity – what happens to come on the market, who happens to divorce or die, at the time in your decades of collecting when you have maximum spending power and time; R is for resources; and K is for knowledge.’ (Perhaps SS, for ‘supportive spouse,’ can be tacked on to the acronym.)

Winnie, with her training in information science, often reminds Michael that he needs to create a formal database of his purchases, recording what he paid and where, and whether he has an eventual institutional home in mind. But he keeps being distracted by the next acquisition, while hosting scholars and fielding loan requests from curators. ‘Those jades are off to the Cleveland Museum of Art,’ he says, pointing to a russet bi disc and a cong – the latter is a hollow pillar, its square exterior representing earth and its cylindrical void symbolising heaven. (They will appear in ‘China’s Southern Paradise: Treasures from the Lower Yangzi Delta’ at the museum this autumn.)

Michael unboxes a 14th-century scroll painting that will soon be loaned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He unrolls a fraction of its 30-foot-long expanse on his dining table and reveals a waterfront tree grove, which the artist Wang Meng based on scenery in his nephew’s home- town. ‘The wind is rustling, you can feel it,’ Michael says. ‘Those reeds,’ he adds, pointing to some feathery clusters along the shore, ‘those were done with one or two hairs on the brush.’ The scroll is stamped with 136 seals from collectors, in varying shades of crimson. Panel after panel of colophons have calligraphy essays from past owners, discussing the artist’s skill and technique, among other topics. Michael asks me to imagine any Western equivalent, perhaps a Vermeer painting, attached to centuries of rolled-up manuscripts, with reminiscences of what it was like to be a temporary custodian of canvas.

A few of the Fengs’ dozens of scroll paintings are framed for display. Near the dining table, a mid 18th-century depiction of an imperial snow falcon, by the Italian Jesuit missionary Giuseppe Castiglione, keeps company with the rearing horse. Among the few other works by Castiglione in the United States, Michael notes, are the Qianlong emperor’s family portraits at the Cleveland Museum and the Met’s tableau of horse-populated landscapes spanning 25 feet. Along the perimeter of the snow falcon’s portrait, past owners, including the Qianlong emperor, emblazoned their seals. The bird has a fierce racing stripe along its face and is secured to its palace perch by a tiny leather leg strap – I try to imagine how little time the artist would have had to sketch the restless captive.

Family photographs include T.V. Soong with FDR and Churchill (top row; centre) Madame Sun photographed by Cecil Beaton in 1944 (middle row; centre left) and Madame Chiang with Eleanor Roosevelt (bottom row, right). Photo: Blaine Davis

In Michael’s library, photographs and memorabilia document the émigré relatives who, during his childhood in New York, spoke little about their painful past. A number of them had studied at American universities and then returned to their homeland, hoping to help it modernise and democratise, before the Communist takeover. T.V. Soong, for example, studied at Harvard and his father Charlie Soong, who had earned a degree at Vanderbilt University in the 1880s, helped Sun Yat-sen overthrow China’s imperial government in 1911. Madame Chiang was a Wellesley graduate, and her sister Madame Sun studied at Wesleyan College in Georgia.

On the library wall, a portrait from 1939 of Madame Chiang in a black satiny outfit studded with metal- lic dots, is hung near Cecil Beaton’s photo of Madame Sun in a flowered dress, taken in 1944 when Beaton was travel- ling on assignment for Britain’s Ministry of Information. Images of T.V. Soong on Michael’s walls and shelves record meetings with Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt and an appearance on the cover of Time magazine in 1944. Michael explains that in 1945, the photographer Yousuf Karsh was given three minutes at a hotel in San

Francisco to take a portrait of T.V. Soong, who paused in a doorway, wearing a tweedy overcoat, managing an intense half-smile as smoke plumed from his cigarette. There is also a photo taken by Winnie in 1995 of an exiled Madame Chiang and her great-nephew Michael admiring and deciphering the colophon of a scroll painting.

The family has donated ‘trunks and trunks of documents’ to Stanford’s Hoover Institution, Michael says. Researchers have been poring through the correspondence with world leaders, and there are many pages that the American military declassified only recently. The Fengs have hung on to other memorabilia, including dealers’ receipts for T.V. Soong’s diplomatic gifts. A sheet of US postage stamps from the 1940s, which portray Abraham Lincoln and Sun Yat-sen as heroes of democracy, is on view near the snow falcon. The inscription along one edge – ‘For my old friend “T.V.”’ – is from Franklin Roosevelt.

Just as the Fengs keep making new acquisitions, more discoveries keep being made about the collection. Within days of my visit, a dragon-encrusted, lidded bronze vessel was delivered, with documentation of its being shown at a London museum in the 1960s. Groups of scholars have made appointments to analyse, for instance, the royal inventory markings on the jades, to determine what was carved where and which pieces were stored next to each other a few millennia ago. And how fitting that these relics of the ancient past sit alongside these remembrances of family members, so many of whom ended up so far from home.

From the February 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)