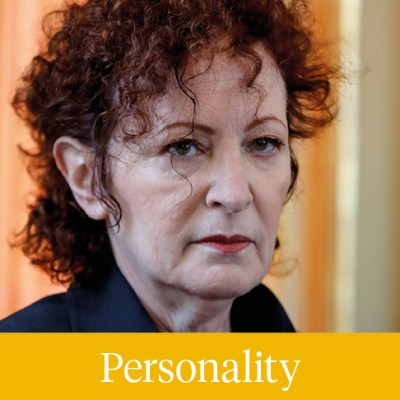

Near the end of Laura Poitras’ documentary All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, Nan Goldin says that ‘The worst things are kept secret, and it destroys people.’ The photographer is talking about her older sister, Barbara, who committed suicide at the age of 19 after their parents, struggling to deal with her rebellion against her middle-class life, put her into various institutions. But she has also been talking about her campaign to persuade the art world to stop taking money from the Sackler family – owners of Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin, the opioid painkiller to which she and hundreds of thousands of Americans have become addicted, often fatally – and to remove its name from the walls of the world’s most prestigious museums. A film containing both strands could have been made at cross-purposes – it began with Goldin wanting to make a documentary about her campaign against the Sacklers, before Poitras also became drawn to telling the story of the artist’s life and career. At times, the viewer can see the joins, but the narrative just about comes together. A mixture of archive footage, talking-head interviews with Goldin and others, and documentary footage of her campaigns, the film provides a fascinating insight into how the difficulty and sadness of Goldin’s childhood drove her work, equipping her with the determination to continue in the face of physical abuse, sex work, poverty, institutional misogyny and homophobia, censorship, and the devastation of the HIV/AIDS epidemic – and then to risk taking on the might and wealth of the Sacklers.

Self-portrait with scratched back after sex, London (1978). Courtesy Nan Goldin

Goldin remains best known for her ongoing photo-series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, featuring images of her friends – actors, artists, queer and trans people, sex workers – and first published as a book in 1986. Poitras presents Goldin’s process as simple: she portrayed her subjects as they wanted to be seen, aware that they lived in a world that often refused to acknowledge who they were and that was indifferent (at best) to a disease that seemed to target them specifically. Along with Barbara, the ghosts here are all the artists, activists and friends lost to AIDS, most notably actor/writer Cookie Mueller, the subject of Goldin’s photographs from 1976, when they met, until Mueller’s death in 1989. Poitras captures Goldin’s understanding that AIDS may have been a force majeure, but the people who chose to ignore its impact – or even celebrate its effects – were using their positions and means in a war against the LGBT+ community.

Goldin developed an addiction to OxyContin after wrist surgery in 2014. She founded PAIN (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) after a recovery programme in 2017. Having fought to retain National Endowmen for the Arts (NEA) funding for several exhibitions of works made by queer artists at the height of the AIDS epidemic, now Goldin was campaigning to make museums reject the funds of those who profiting from the opioid crisis. At a time when the art world’s sources of funding have come under greater scrutiny, Goldin focused on the Sackler family, who, she explains, have made billions from the aggressive marketing and sale of OxyContin since 1996, and prominent ‘artwashers’, salving their consciences by donating to major museums – including plenty that hold her work. The legacy of 80s’ direct activism (and ACT-UP, in particular) comes across in PAIN’s focused, well-coordinated and visually effective interventions – such as dropping a ‘blizzard’ of prescriptions from the balconies at the Guggenheim Museum in New York and staging a ‘die-in’ on the ground floor. The conversations about how Goldin’s visibility as an activist might affect her career are especially striking: Goldin decides that it is better to be excluded for being vocal than to stay on the inside and keep silent. It’s a decision that carries extra weight after we learn that Goldin barely spoke for years after her sister’s death

Nan Goldin in a protest with family members of people who have died during the opioid epidemic, protesting against a bankruptcy deal with Purdue Pharmaceuticals outside the Federal courthouse in White Plains, NY. Photo: Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images

Poster for All the Beauty and the Bloodshed

Heard only as an off-camera voice supporting Goldin through some of her hardest recollections, Poitras keeps her presence to a minimum, but it feels as if a friendship develops during the making of the film, strengthening its emotional core. And All the Beauty and the Bloodshed is an emotive film, reminding the viewer that behind every statistic about HIV/AIDS or the opioid crisis, is a life, often lived in adversity – even if, as is often the case with Goldin’s friends and acquaintances, that adversity is met with creative defiance. We can see joy in the incredible successes of PAIN’s campaigns, and defiance in a Zoom meeting with the Sacklers, in which they are confronted with the human cost of their greed. The story of Goldin’s life and of her campaigning should inspire others should be an inspiration for people to make art, to become involved in activism, and to keep finding ways to combine the two.

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (dir. Laura Poitras) is released in UK cinemas on 27 January.