Neanderthals went fishing, cooked over hearths, ground paints, explored deep caves, and sometimes buried their dead. They made complex stone tools, pendant jewellery, and chemical adhesives. Their species thrived for 250,000 years, through multiple ice ages, across diverse ecosystems, from Britain to Gibraltar to Uzbekistan. They are our extinct cousins, whose DNA lives on in modern humans due to interbreeding. Still, the old trope persists: Neanderthals as poor, stooped brutes communicating with simple guttural sounds, eking out a violent life in the margins of survival. It’s unfortunate, when the details actually point to an intelligent, resourceful, adventurous and emotional species.

And now once again, a new discovery, this time the oldest evidence of fibre technology, has made us examine what Neanderthal life was really like. (The study was published on 9 April in Scientific Reports.) Twisted plant fibres were found adhered to a stone tool from an excavation at Abri du Maras in southern France. ‘Abri’ is the French word for ‘shelter’, and rock shelters have been inhabited by people for hundreds of thousands of years and into modern times. Thousands of stone artefacts as well as evidence of fire were revealed, in layers showing Neanderthal occupation. The stone tool with the fibres was found in these layers, dated to between 41,000 and 52,000 years ago.

Excavation of Abri du Maras. Photo: M-H. Moncel

A simple string is not so simple. Under reflected light microscopy, which allowed an extremely high-resolution image, pictures show a 6.2mm-long, 0.5mm-thick three-ply string, with each ply twisted counter-clockwise, and then the three twisted together in a clockwise direction. Doing this locks the fibres together and prevents it from unravelling, creating an exponentially stronger material. It’s the same engineering you find with metal cables holding up suspension bridges, or rope on sailing ships.

This discovery is exciting enough, as organic technologies are usually long rotted away, and archaeologists are left with only stones and bones except in rare circumstances. But impressive technology like this also gives us gratifying glimpses into Neanderthals’ minds. Making strong string is unlikely to have been invented just in that instance by one individual. It’s more likely that community knowledge of the technique was acquired and passed on through imitation or direct instruction from generation to generation. Learning through imitation is rarer in the animal kingdom than one would think. In fact, non-human apes don’t often ‘ape’ each other. Humans are particularly skilled at it – though anyone who has been to a beginners’ dance class knows that copying the bodily movements of another is very challenging without motivation and practice. This ability – which is intrinsically related to understanding the thoughts of others, and developing language – is cultivated from birth in an environment that rewards ‘do as I do’ behaviour.

The tool that the twisted fibres of Abri du Maras were found on is called a Levallois flake. Levallois is a technique that modern flintknappers find extremely difficult to learn, as it involves shaping a stone before striking off one expertly planned flake. It is robust, thin, and perfect for attaching to a spear – and classic Neanderthal technology. It is possible that the fibres found on the Levallois flake’s underside were part of cord wound around its base to attach it to a shaft. Although, it could equally have been from a bag, or something unrelated to the tool. Recently examined eagle talons, which Neanderthals have been known to collect, show evidence of being strung. Could this have been on plant fibres similar to those found at Abri du Maras?

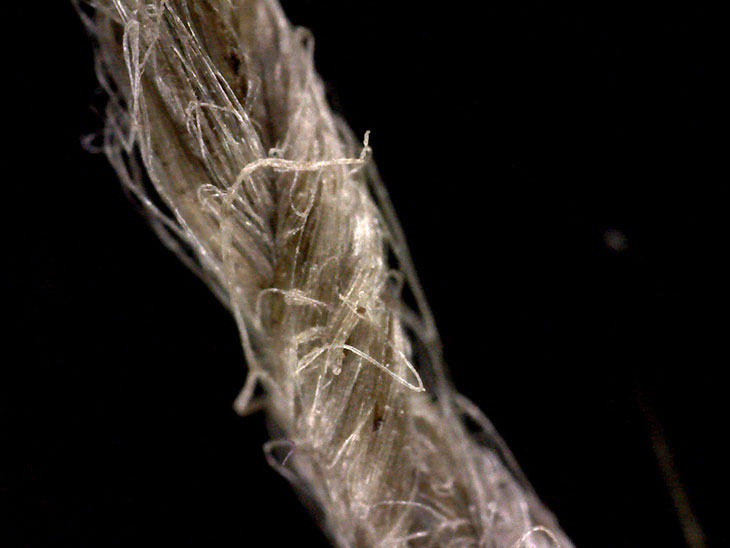

Close-up of modern flax cordage showing twisted fibre construction. Photo: S. Deryck

The fibres themselves appear to specialists to be from the bark of a coniferous tree. Today, groups around the world – such as the First Nations communities of the Pacific Northwest – use the inner bark from trees such as lime or cedar, for use in bags and mats, baskets and even detailed woven garments. People harvest these plant materials in particular seasons, and may treat fibres by soaking them in water beforehand, a process called retting. This improves their durability and strength, as the fibres may splinter when twisting otherwise. If Neanderthal technology included this level of knowledge, forward planning and detail, we owe it to them to remember this species as they were – engineers, craftspeople, and artists on a par with their close relatives.

Cory Stade is a Visiting Fellow at the Centre for the Archaeology of Human Origins at the University of Southampton.

String theory – what an ancient cord fragment reveals about the Neanderthal mind

A scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of the cord fragment found at Abri du Maras. Photo: M-H. Moncel

Share

Neanderthals went fishing, cooked over hearths, ground paints, explored deep caves, and sometimes buried their dead. They made complex stone tools, pendant jewellery, and chemical adhesives. Their species thrived for 250,000 years, through multiple ice ages, across diverse ecosystems, from Britain to Gibraltar to Uzbekistan. They are our extinct cousins, whose DNA lives on in modern humans due to interbreeding. Still, the old trope persists: Neanderthals as poor, stooped brutes communicating with simple guttural sounds, eking out a violent life in the margins of survival. It’s unfortunate, when the details actually point to an intelligent, resourceful, adventurous and emotional species.

And now once again, a new discovery, this time the oldest evidence of fibre technology, has made us examine what Neanderthal life was really like. (The study was published on 9 April in Scientific Reports.) Twisted plant fibres were found adhered to a stone tool from an excavation at Abri du Maras in southern France. ‘Abri’ is the French word for ‘shelter’, and rock shelters have been inhabited by people for hundreds of thousands of years and into modern times. Thousands of stone artefacts as well as evidence of fire were revealed, in layers showing Neanderthal occupation. The stone tool with the fibres was found in these layers, dated to between 41,000 and 52,000 years ago.

Excavation of Abri du Maras. Photo: M-H. Moncel

A simple string is not so simple. Under reflected light microscopy, which allowed an extremely high-resolution image, pictures show a 6.2mm-long, 0.5mm-thick three-ply string, with each ply twisted counter-clockwise, and then the three twisted together in a clockwise direction. Doing this locks the fibres together and prevents it from unravelling, creating an exponentially stronger material. It’s the same engineering you find with metal cables holding up suspension bridges, or rope on sailing ships.

This discovery is exciting enough, as organic technologies are usually long rotted away, and archaeologists are left with only stones and bones except in rare circumstances. But impressive technology like this also gives us gratifying glimpses into Neanderthals’ minds. Making strong string is unlikely to have been invented just in that instance by one individual. It’s more likely that community knowledge of the technique was acquired and passed on through imitation or direct instruction from generation to generation. Learning through imitation is rarer in the animal kingdom than one would think. In fact, non-human apes don’t often ‘ape’ each other. Humans are particularly skilled at it – though anyone who has been to a beginners’ dance class knows that copying the bodily movements of another is very challenging without motivation and practice. This ability – which is intrinsically related to understanding the thoughts of others, and developing language – is cultivated from birth in an environment that rewards ‘do as I do’ behaviour.

The tool that the twisted fibres of Abri du Maras were found on is called a Levallois flake. Levallois is a technique that modern flintknappers find extremely difficult to learn, as it involves shaping a stone before striking off one expertly planned flake. It is robust, thin, and perfect for attaching to a spear – and classic Neanderthal technology. It is possible that the fibres found on the Levallois flake’s underside were part of cord wound around its base to attach it to a shaft. Although, it could equally have been from a bag, or something unrelated to the tool. Recently examined eagle talons, which Neanderthals have been known to collect, show evidence of being strung. Could this have been on plant fibres similar to those found at Abri du Maras?

Close-up of modern flax cordage showing twisted fibre construction. Photo: S. Deryck

The fibres themselves appear to specialists to be from the bark of a coniferous tree. Today, groups around the world – such as the First Nations communities of the Pacific Northwest – use the inner bark from trees such as lime or cedar, for use in bags and mats, baskets and even detailed woven garments. People harvest these plant materials in particular seasons, and may treat fibres by soaking them in water beforehand, a process called retting. This improves their durability and strength, as the fibres may splinter when twisting otherwise. If Neanderthal technology included this level of knowledge, forward planning and detail, we owe it to them to remember this species as they were – engineers, craftspeople, and artists on a par with their close relatives.

Cory Stade is a Visiting Fellow at the Centre for the Archaeology of Human Origins at the University of Southampton.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

The oldest drawing in the world has been discovered – but is it art?

A 73,000-year-old fragment of stone marked with red lines raises questions about the nature of aesthetic experience

Unearthing the secrets of the Anglo-Saxon world

Paganism and Christianity are intertwined in the hoard of rare artefacts found in a princely burial site in Essex

Has the tomb of Romulus really been found – or is someone crying wolf?

Claims that the resting place of the legendary founder of Rome has been discovered cause Rakewell to raise an eyebrow