This month, Christie’s and Sotheby’s are selling artworks from the 20th and 21st centuries to create what they will hope will be record-breaking auctions – Andy Warhol’s 1964 silk-screen portrait of Marilyn Monroe has already broken one record by fetching the cool sum of $195 million, the highest price ever paid for an American artwork at auction. It is against this backdrop that the state of New York has eliminated some of the protections that govern auctions in that jurisdiction (as revealed by recent article in the The New York Times), effectively creating a free-for-all in the largest art market in the world. Unlike the banking industry, the art trade has few rules that govern its dynamics, but for Americans it seems that even these are too many.

Thinking of art auctions, one imagines nattily-dressed elites bidding on masterpieces to set new auction records. It seems like the market mechanism at its finest, with plenty of well-funded participants who gather to set the established prices for publicly-traded merchandise which is very tricky to value otherwise. For all of their publicity and flair, however, auctions are hard to follow: the slightest gesture might be interpreted as a bid and change the dynamic in the room, driving a price for a work of art far beyond expectations. This is why auctioneers create fake bids, a practice commonly known as “chandelier bidding” in the art world. In order to get a work of art to its price floor (the reserve price the seller has agreed to), auctioneers are allowed to ‘find’ bids that do not exist in order to liven up the room and push the bidding into a competitive environment. Until last week, this activity was not allowed once the price floor had been breached so that any competition between bidders from that point onwards was real. Now, auction houses can juice the bids as far as they like without breaking any rules and to add further fuel to the fire, they no longer have to disclose to consumers when the auction house itself has a financial stake in the outcome of the sale.

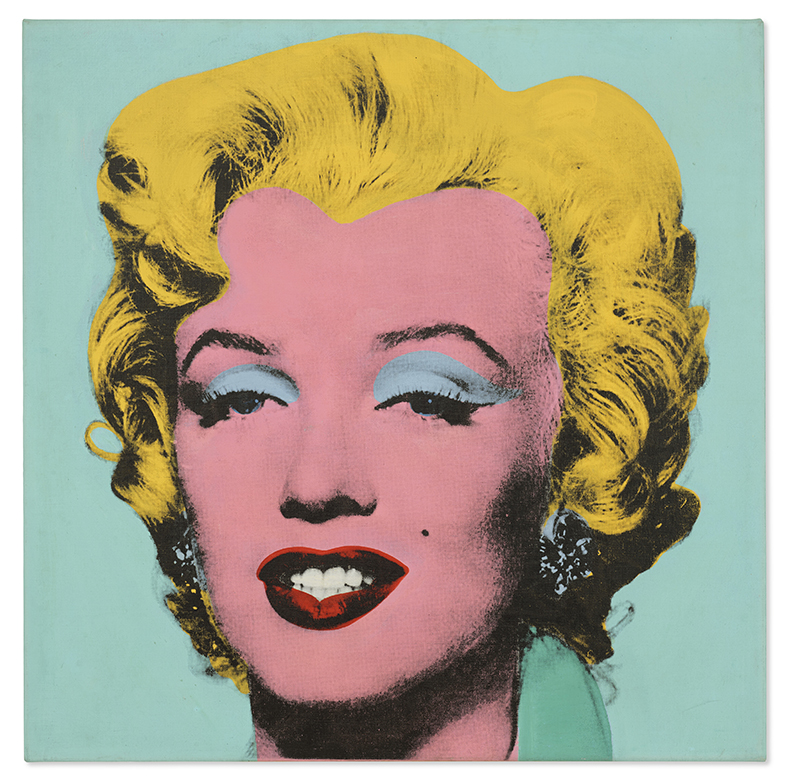

Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (1964), Andy Warhol. Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd. 2022.

In their defence, art auction houses have stated that their customers are not only well-heeled, but also well informed. In other words, they know what kind of business they are getting into and consumer protections such as these recently reversed rules are not necessary. This logic – rich people don’t get snookered – ignores plenty of evidence but who is going to go to the mat to protect a bunch of champagne-sipping art collectors?

But why get rid of consumer protection rules meant to minimise fraud? The city claims that it is simply updating ordinances to create a more consumer-friendly environment. Some auction houses, who seem to have been genuinely surprised by this decision, have announced that they are not planning to shift practices (though, notably, Sotheby’s would not comment publicly on how it will respond). Experts interviewed by Graham Bowley and Robin Pogrebin in The New York Times suggested that the main issue is one of trust and that, if the art market participants do not trust the auction houses, it would be bad for business. This bears repeating: if governments are determined to slash their oversight on some of the lightest regulated industries, they may gain market share but what they lose in the bargain is legitimacy.

A bidder at an auction at Christie’s New York. Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Another example of lax regulation in the United States will help to demonstrate this point. Recent rules introduced to eliminate money laundering in Europe (AMLD5) target art buyers who obscure their identity through trusts and shell companies. It may be that almost all of the people who employ these devices to avoid identification are legitimate business people who simply wish to remain discrete – but we will never know until someone leaks the documents. What has been revealed through the Panama Papers and other leaks, is the use of offshore secrecy jurisdictions to prevent regulatory authorities from knowing who owns what and where it is stored. It is not illegal to hide money in a secrecy jurisdiction, but most folks (and companies) who do so are saving taxes and that means fewer revenues for governments to do their work. When governments slash regulations to cultivate a more desirable business environment, they undermine themselves. If all countries get on board with anti-money laundering directives, they will have teeth. Yet offshore jurisdictions will allow those with the means to continue to flout the law.

As the birthplace of neoliberalism, America has long sought to pursue economic goals in a regulation-free environment. The U.S. Treasury Department put out a report on money laundering and the art market in February 2022 which stated that there was no need to impose anti-money laundering regulations in the art market because there is not ample enough evidence to suggest its taking place. Could that be because the perpetrators are succeeding in hiding it? To say that there is no cheating because we have not seen it begs the question of whether the speaker is conveniently ignoring it. By cutting regulations and refusing to impose anti-money laundering directives adopted by Europe and the United Kingdom, the United States is effectively telling us that no one cheats in the art market. Who among us is gullible enough to believe that?

Risky business – why is New York getting rid of auction regulations?

Photo: Malcolm Park/Alamy Stock Photo

Share

This month, Christie’s and Sotheby’s are selling artworks from the 20th and 21st centuries to create what they will hope will be record-breaking auctions – Andy Warhol’s 1964 silk-screen portrait of Marilyn Monroe has already broken one record by fetching the cool sum of $195 million, the highest price ever paid for an American artwork at auction. It is against this backdrop that the state of New York has eliminated some of the protections that govern auctions in that jurisdiction (as revealed by recent article in the The New York Times), effectively creating a free-for-all in the largest art market in the world. Unlike the banking industry, the art trade has few rules that govern its dynamics, but for Americans it seems that even these are too many.

Thinking of art auctions, one imagines nattily-dressed elites bidding on masterpieces to set new auction records. It seems like the market mechanism at its finest, with plenty of well-funded participants who gather to set the established prices for publicly-traded merchandise which is very tricky to value otherwise. For all of their publicity and flair, however, auctions are hard to follow: the slightest gesture might be interpreted as a bid and change the dynamic in the room, driving a price for a work of art far beyond expectations. This is why auctioneers create fake bids, a practice commonly known as “chandelier bidding” in the art world. In order to get a work of art to its price floor (the reserve price the seller has agreed to), auctioneers are allowed to ‘find’ bids that do not exist in order to liven up the room and push the bidding into a competitive environment. Until last week, this activity was not allowed once the price floor had been breached so that any competition between bidders from that point onwards was real. Now, auction houses can juice the bids as far as they like without breaking any rules and to add further fuel to the fire, they no longer have to disclose to consumers when the auction house itself has a financial stake in the outcome of the sale.

Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (1964), Andy Warhol. Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd. 2022.

In their defence, art auction houses have stated that their customers are not only well-heeled, but also well informed. In other words, they know what kind of business they are getting into and consumer protections such as these recently reversed rules are not necessary. This logic – rich people don’t get snookered – ignores plenty of evidence but who is going to go to the mat to protect a bunch of champagne-sipping art collectors?

But why get rid of consumer protection rules meant to minimise fraud? The city claims that it is simply updating ordinances to create a more consumer-friendly environment. Some auction houses, who seem to have been genuinely surprised by this decision, have announced that they are not planning to shift practices (though, notably, Sotheby’s would not comment publicly on how it will respond). Experts interviewed by Graham Bowley and Robin Pogrebin in The New York Times suggested that the main issue is one of trust and that, if the art market participants do not trust the auction houses, it would be bad for business. This bears repeating: if governments are determined to slash their oversight on some of the lightest regulated industries, they may gain market share but what they lose in the bargain is legitimacy.

A bidder at an auction at Christie’s New York. Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Another example of lax regulation in the United States will help to demonstrate this point. Recent rules introduced to eliminate money laundering in Europe (AMLD5) target art buyers who obscure their identity through trusts and shell companies. It may be that almost all of the people who employ these devices to avoid identification are legitimate business people who simply wish to remain discrete – but we will never know until someone leaks the documents. What has been revealed through the Panama Papers and other leaks, is the use of offshore secrecy jurisdictions to prevent regulatory authorities from knowing who owns what and where it is stored. It is not illegal to hide money in a secrecy jurisdiction, but most folks (and companies) who do so are saving taxes and that means fewer revenues for governments to do their work. When governments slash regulations to cultivate a more desirable business environment, they undermine themselves. If all countries get on board with anti-money laundering directives, they will have teeth. Yet offshore jurisdictions will allow those with the means to continue to flout the law.

As the birthplace of neoliberalism, America has long sought to pursue economic goals in a regulation-free environment. The U.S. Treasury Department put out a report on money laundering and the art market in February 2022 which stated that there was no need to impose anti-money laundering regulations in the art market because there is not ample enough evidence to suggest its taking place. Could that be because the perpetrators are succeeding in hiding it? To say that there is no cheating because we have not seen it begs the question of whether the speaker is conveniently ignoring it. By cutting regulations and refusing to impose anti-money laundering directives adopted by Europe and the United Kingdom, the United States is effectively telling us that no one cheats in the art market. Who among us is gullible enough to believe that?

Share

Recommended for you

Sterling efforts – what to make of the London art market’s resurgence?

Recent auction results suggest a return to pre-pandemic levels – but with turmoil engulfing Europe, this raises some difficult questions

Around the galleries – Frieze hits New York, plus other highlights

A more local, intimate Frieze returns to the Shed – and Apollo picks out four of the best shows at London Gallery Weekend

The art world’s problem with Russian money

As the number of global billionaires has ballooned, the art world has become increasingly reliable on questionable funds from Russia and elsewhere