In Georgia, feasting is a national pastime. ‘If a neighbour’s cousin’s dog had a puppy,’ the London-based restaurateur Tiko Tuskadze writes, ‘we would laugh and celebrate with a feast until dawn.’ In her Georgian cookbook, Tuskadze describes a typical banquet, or supra, as a choreographed but cheerfully ramshackle affair: a ‘procession of dishes’ laid on the table, a series of toasts by a designated tamada (toastmaster), music and a liberal supply of Georgian wine. If you’re feasting in Kakheti, the principal wine-growing region, the booze might be drawn directly from a qvevri, an earthenware vessel so vast that Diogenes would mistake it for a luxury apartment.

The writer Wendell Steavenson, who spent a couple of years as a foreign correspondent in Tbilisi, is more sceptical about the supra. It’s not that she doubts Georgian hospitality, but in its performance she senses a type of nostalgia, tinged with exceptionalism, for a golden age that probably never was. ‘Thirty years the same idiots sit around a table and repeat the same toasts,’ a Georgian friend tells Steavenson in Stories I Stole (2002), her memoir of life in the Caucasus. ‘They are only words and insincere.’ Still, we’re three months into lockdown, so any company sounds like good company at this point.

Tatar Fruiterer (n.d.), Niko Pirosmani. Georgian National Museum, Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi. © Infinitart Foundation

One of the conduits of supra nostalgia, no doubt, is the work of Niko Pirosmani (Nikala Pirosmanashvili; 1862?–1918), who has taken on the guise of Georgia’s national painter in the century since he died in poverty and relative obscurity. Pirosmani’s surviving works include numerous images of feasts, along with all manner of beasts, individual figures at work and scenes of rural life. The banquet paintings, in particular, have becomes touchstones of Georgian conviviality, widely reproduced in Tbilisi and beyond. ‘There is probably not a single Georgian restaurant […] around the world,’ the scholar Régis Gayraud writes, ‘that doesn’t feature on one of its walls a reproduction of a painting by this man who so often went hungry.’

Little is known about Pirosmani’s life (which rather adds to his myth), beyond that he spent several decades as a jobbing painter, making signs and probably distemper murals for shops and taverns in Tbilisi and trading his art for meals and a roof over his head. Successful sign painting demands graphic clarity, an obligation that must have contributed to Pirosmani’s distinctive style, with its bold forms, sparing palette and frugal use of detail. His facility in handling oil paint was entirely his own, as was his use of black wax cloth as his preferred support. He often let the fabric show through to create emphatic outlines or, in works such as Fisherman in a Red Shirt, a beguiling night-for-day atmosphere. (The self-taught Pirosmani is often described as a ‘naive’ painter, but as the catalogue for an exhibition of his work in Vienna and Arles in 2018–19 makes clear, unlike, say, Alfred Wallis, he never simply improvised with whatever materials were at hand.)

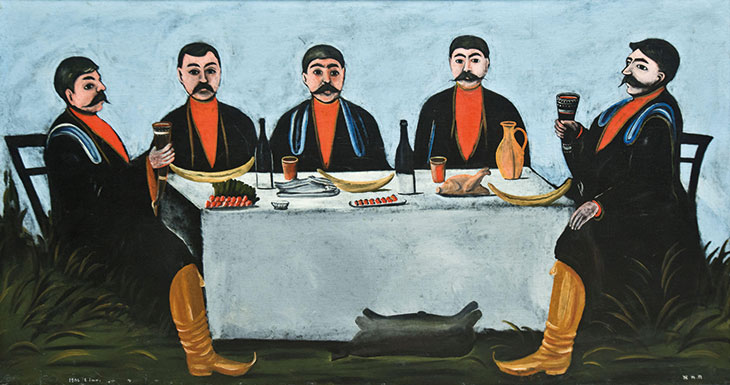

The Banquet of Five Princes (1906), Niko Pirosmani. Photo: Mariano Garcia/Alamy Stock Photo

Pirosmani favoured a frontal composition for his figures, perhaps drawing on the precepts of Byzantine icon painting or even Qajar portraiture. This gives his banqueting scenes a confident directness: his diners are usually mid toast, gesturing to the world beyond the painting and forever inviting the viewer to raise a glass with them. Perhaps ironically, given their subject, but in keeping with Pirosmani’s parsimonious approach, these feast paintings show tables more spartan than one might expect. Most are laid with a few fish, a chicken and perhaps a plate of radishes, although there is often a waiter carrying more food or wine into view.

Detail of The Banquet of Five Princes (1906), Niko Pirosmani. Photo: the author

All the same, Pirosmani evidently took pleasure in the forms of food. In The Banquet of Five Princes, the boat-shaped bread (khachapuri) rhymes with the curling toes of the princes’ boots, as though the assembled company might be about to gorge on itself. From a distance, his piles of radishes appear to have a coherent volume; up close, you can see how quickly he painted them, alla prima, the paint rippled red and white like a squirt of stripy toothpaste.

‘We ought to buy a big table and a big samovar and drink a lot of tea, and talk about painting and art.’ So Pirosmani told his fellow artists in 1916, when – having attracted the notice of the Russian avant-garde – he was invited to a meeting of the newly formed Georgian Art Society. Painting tavern signs, decorating the walls of dining rooms, looking to make a crust from his art: in his mind Pirosmani was never far from the Georgian table, even if he never had a fixed place at it.

Feast with Datiko Zemel, the Organ Grinder (n.d.), Niko Pirosmani. Georgian National Museum, Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi. Photo: the author

From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)