As we approach ICOMOS’s International Day for Monuments and Sites (18 April) it is worth celebrating that Syrian government forces have retaken the ancient city of Palmyra from ISIS. Over the past year this World Heritage Site has become a cultural battleground for Islamist extremists who reject alternative ideologies. The potent symbol of the destruction of the 2,000-year-old Temple of Bel last September was made more shocking by the knowledge that this ancient city was built on its trading links. A dispiriting moment for a place that flourished on tolerance and diversity – a place where Greek, Roman, Persian, Arab, Phoenician and local traditions combined and prospered.

Now, with ISIS gone, there will be an opportunity to review what Syria and the world has lost. Our first reaction is horror and offence. These are globally significant remains that have been destroyed on the grounds of ideology and, frankly, in order to loot and grab headlines.

ISIS can try to redact Palmyra from our collective memory. But they will fail. The genie flew out of the bottle in the 18th century, when a series of beautiful drawings were published that inspired the neoclassical movement and influenced hundreds of buildings in Britain, continental Europe and America.

In 1751, Robert Wood and James ‘Jamaica’ Dawkins, with the Italian architect Giovanni Battista Borra, travelled to Palmyra in Syria and Baalbek in Lebanon, via Italy and Turkey.

James Dawkins and Robert Wood Discovering the Ruins of Palmyra (1758), Gavin Hamilton.

They spent five days in the ancient city recording the wonderfully preserved ruins, and subsequently published The ruins of Palmyra, otherwise Tedmore in the desart (sic) in both English and French in 1753. Back home a burgeoning interest in the classical world, fuelled by the tradition of the Grand Tour, created a thirst for authentic and original classical styles. Wood’s book, with its accurate illustrations, was the first of a handful of source manuals that fed the new architectural movement (others included James Stuart and Nicholas Revett’s Antiquities of Athens, 1762, and Robert Adam’s Palace of Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia, 1764).

Plate from The Ruins of Palmyra (1753), by Robert Wood.

Walk through the piano nobile at Stowe House in Buckinghamshire to the Garter Room or State Bedroom at the end of the western enfilade. Look up. There is a precise copy of the coffered ceiling from the Great Temple of Bel. Go outside to the Temple of Concord and Victory, and there it is again.

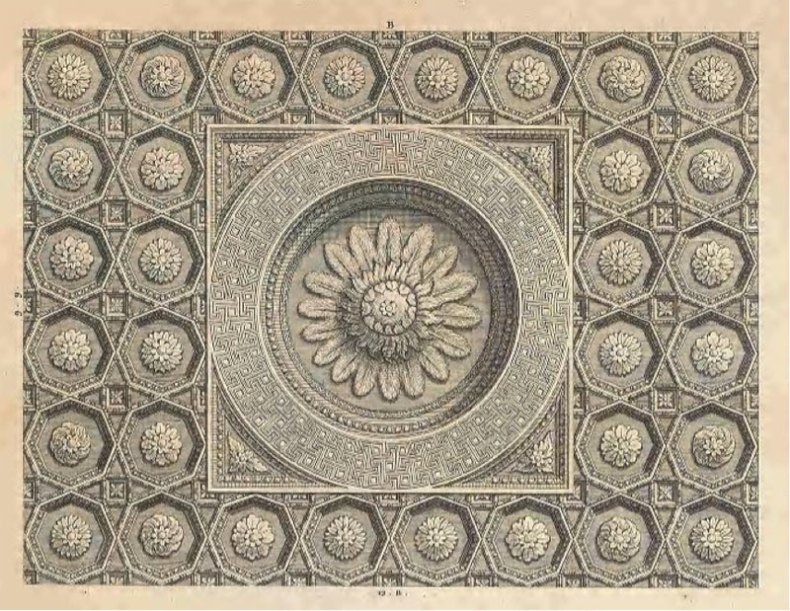

Palmyrene ceiling in the Garter Room, Stowe House, Buckinghamshire

Ceiling detail from Wood’s The Ruins of Palmyra (1753)

And who was the architect advising Lord Cobham at Stowe in the 1750s? None other than our friend Giovanni Battista Borra, who worked there on his return from Syria, making Stowe’s garter room ceiling ‘the first room in the modern world’ to be based on the now destroyed temple.

Ceiling from the Temple of Concord and Victory, Stowe. © Emma Galvin

Ceiling from the Temple of Concord and Victory, Stowe. © Emma Galvin

Repeat the exercise in some of the great chambers of the UK’s greatest houses – the State Bedroom at Woburn Abbey, the dining room at Stratfield Saye, the church at West Wycombe, the study at Harewood House, Chiswick House, Kensington Palace – and again, you will find a small piece of Syria.

The Ruins of Palmyra was a hit, moving artists such as Gavin Hamilton, the poets Browning and Diderot and an exuberant Horace Walpole, who wrote ‘of all the works that distinguish this age, none perhaps excel those beautiful editions of Balbek and Palmyra’. The descriptions and 57 plates taken from Borra’s drawings inspired more than a fleeting fad for coffered Palmyrene ceilings. They became templates for architectural details and entire façades – the entrance front at Osterley Park, for instance, takes its inspiration from the Temple of the Sun.

The entrance front at Osterley

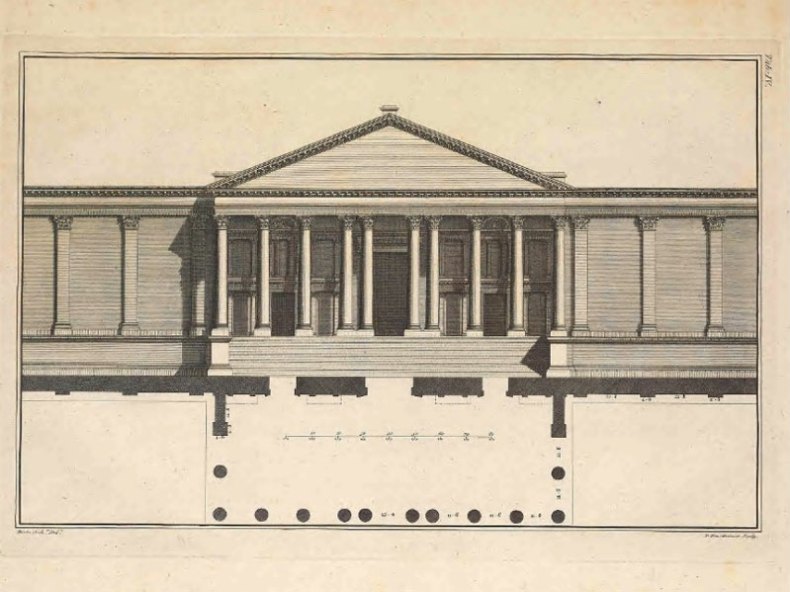

Elevation of the great temple from The Ruins of Palmyra

I applaud my friend Professor Maamoun Abdulkarim, Syria’s Director General of Antiquities, for his recent promise at a WMFB talk to ‘rebuild’ Palmyra, and I support efforts to conserve, record and even reconstruct these and other cultural icons so that they cannot be removed from history. It is proposed that a version of Palmyra’s arch will be recreated in Trafalgar Square on 19 April.

These things need to happen. But Palmyra has already spawned a thousand imitations – the legacy of this extraordinary place is very much alive and much closer to home than most people think.

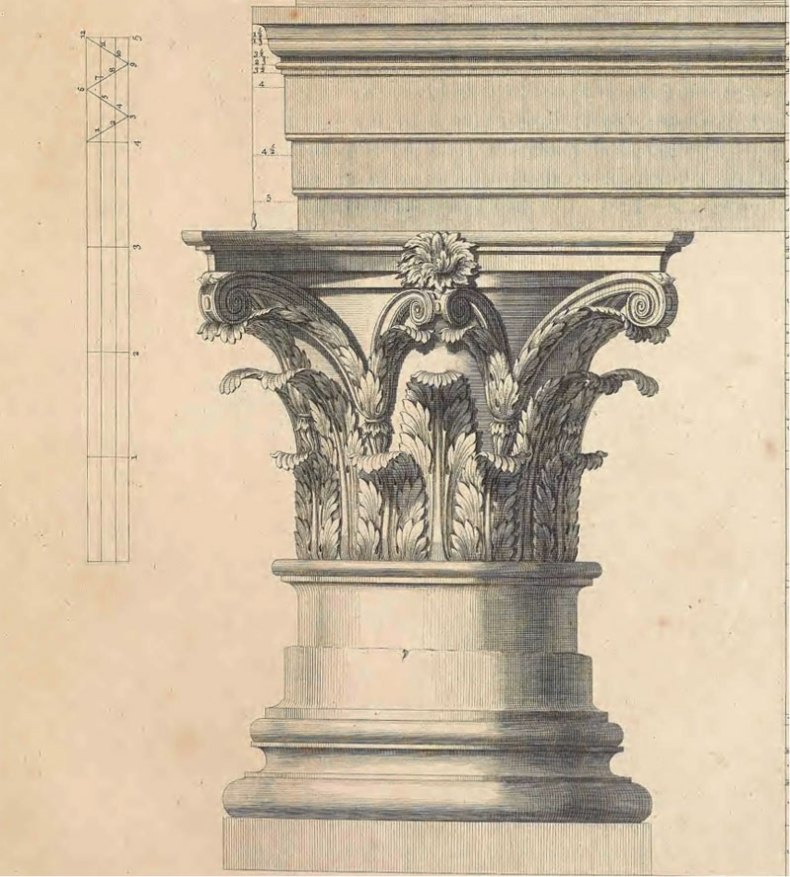

One of Borra’s beautiful and accurate drawings from Palmyra

Palmyra’s legacy is everywhere – and ISIS could never have erased it

Plate from The Ruins of Palmyra (1753), by Robert Wood.

Share

As we approach ICOMOS’s International Day for Monuments and Sites (18 April) it is worth celebrating that Syrian government forces have retaken the ancient city of Palmyra from ISIS. Over the past year this World Heritage Site has become a cultural battleground for Islamist extremists who reject alternative ideologies. The potent symbol of the destruction of the 2,000-year-old Temple of Bel last September was made more shocking by the knowledge that this ancient city was built on its trading links. A dispiriting moment for a place that flourished on tolerance and diversity – a place where Greek, Roman, Persian, Arab, Phoenician and local traditions combined and prospered.

Now, with ISIS gone, there will be an opportunity to review what Syria and the world has lost. Our first reaction is horror and offence. These are globally significant remains that have been destroyed on the grounds of ideology and, frankly, in order to loot and grab headlines.

ISIS can try to redact Palmyra from our collective memory. But they will fail. The genie flew out of the bottle in the 18th century, when a series of beautiful drawings were published that inspired the neoclassical movement and influenced hundreds of buildings in Britain, continental Europe and America.

In 1751, Robert Wood and James ‘Jamaica’ Dawkins, with the Italian architect Giovanni Battista Borra, travelled to Palmyra in Syria and Baalbek in Lebanon, via Italy and Turkey.

James Dawkins and Robert Wood Discovering the Ruins of Palmyra (1758), Gavin Hamilton.

They spent five days in the ancient city recording the wonderfully preserved ruins, and subsequently published The ruins of Palmyra, otherwise Tedmore in the desart (sic) in both English and French in 1753. Back home a burgeoning interest in the classical world, fuelled by the tradition of the Grand Tour, created a thirst for authentic and original classical styles. Wood’s book, with its accurate illustrations, was the first of a handful of source manuals that fed the new architectural movement (others included James Stuart and Nicholas Revett’s Antiquities of Athens, 1762, and Robert Adam’s Palace of Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia, 1764).

Plate from The Ruins of Palmyra (1753), by Robert Wood.

Walk through the piano nobile at Stowe House in Buckinghamshire to the Garter Room or State Bedroom at the end of the western enfilade. Look up. There is a precise copy of the coffered ceiling from the Great Temple of Bel. Go outside to the Temple of Concord and Victory, and there it is again.

Palmyrene ceiling in the Garter Room, Stowe House, Buckinghamshire

Ceiling detail from Wood’s The Ruins of Palmyra (1753)

And who was the architect advising Lord Cobham at Stowe in the 1750s? None other than our friend Giovanni Battista Borra, who worked there on his return from Syria, making Stowe’s garter room ceiling ‘the first room in the modern world’ to be based on the now destroyed temple.

Ceiling from the Temple of Concord and Victory, Stowe. © Emma Galvin

Ceiling from the Temple of Concord and Victory, Stowe. © Emma Galvin

Repeat the exercise in some of the great chambers of the UK’s greatest houses – the State Bedroom at Woburn Abbey, the dining room at Stratfield Saye, the church at West Wycombe, the study at Harewood House, Chiswick House, Kensington Palace – and again, you will find a small piece of Syria.

The Ruins of Palmyra was a hit, moving artists such as Gavin Hamilton, the poets Browning and Diderot and an exuberant Horace Walpole, who wrote ‘of all the works that distinguish this age, none perhaps excel those beautiful editions of Balbek and Palmyra’. The descriptions and 57 plates taken from Borra’s drawings inspired more than a fleeting fad for coffered Palmyrene ceilings. They became templates for architectural details and entire façades – the entrance front at Osterley Park, for instance, takes its inspiration from the Temple of the Sun.

The entrance front at Osterley

Elevation of the great temple from The Ruins of Palmyra

I applaud my friend Professor Maamoun Abdulkarim, Syria’s Director General of Antiquities, for his recent promise at a WMFB talk to ‘rebuild’ Palmyra, and I support efforts to conserve, record and even reconstruct these and other cultural icons so that they cannot be removed from history. It is proposed that a version of Palmyra’s arch will be recreated in Trafalgar Square on 19 April.

These things need to happen. But Palmyra has already spawned a thousand imitations – the legacy of this extraordinary place is very much alive and much closer to home than most people think.

One of Borra’s beautiful and accurate drawings from Palmyra

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

‘We have one heritage.’ Syria’s chief of antiquities calls on Europe for help

‘The dangers surrounding the Syrian archaeological heritage are growing beyond our capabilities’

One museum’s tribute to the murdered Syrian archaeologist, Khaled al-Asaad

How the MFA Boston is paying tribute to a respected scholar and humanist

Treasures from Palmyra preserved in the world’s museums

As ISIS destroys the site, these items are more important than ever