‘Paris Noir’ is the final exhibition in the Centre Pompidou’s top-floor gallery spaces before it closes for a five-year renovation this autumn. It shows the works of 150 African, American and Caribbean artists who lived and worked in Paris between the 1950s and the end of the ’90s, illustrating how the French capital became an important meeting place for artists of the African diaspora after the Second World War.

One of these artists was the American writer William Gardner Smith, who moved to Paris in 1951, joining a community of other expatriate Black writers such as James Baldwin and Chester Himes. A video in the first room of the exhibition shows him telling an interviewer in French, ‘For us Black people, there is a lot less racism here.’ For anyone familiar with contemporary French society that sentiment feels almost laughable, but it reflects the sense of liberation that Black Americans felt in the streets of Paris compared to the segregation and oppression they endured back home. It was a different experience for those artists who had come from France’s colonies and overseas départements, and the show also tracks the rise of the Négritude movement, which came about as a protest against French society’s demands of assimilation.

Umbral (1950), Wifredo Lam. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Photo: © Georges Meguerditchian/Centre Pompidou, MNAM- CCI/Dist. Grand Palais Rmn; © Succession Wifredo Lam, Adagp, Paris, 2025

The exhibition cycles rapidly through different movements in the visual arts, from Afro-Atlantic Surrealism (Wifredo Lam) to compositions inspired by free jazz (Romare Bearden) and new forms of abstraction (Ed Clark and Guido Llinás). Many of the artists haven’t been shown in France before – particularly those who lived there or came from French colonies or overseas territories – and curator Alicia Knock has described the difficulty of tracking down their work in galleries and private collections across the world. Diversity is both the exhibition’s strength and its weakness: the visitor is confronted with the astonishing richness and variety of the production of Black artists in those few decades, but each movement is presented too sparingly. Sometimes one room can be hard to distinguish from another. The painter Beauford Delaney, a close friend of James Baldwin’s (about whom the latter wrote, ‘I learned about light from […] Delaney, the light contained in everything, in every surface, in every face’), seems to be represented in almost every room, several times. His mustard-yellow, paint-thick canvases are undeniably striking, but it’s not easy to understand the point the exhibition is making with each work.

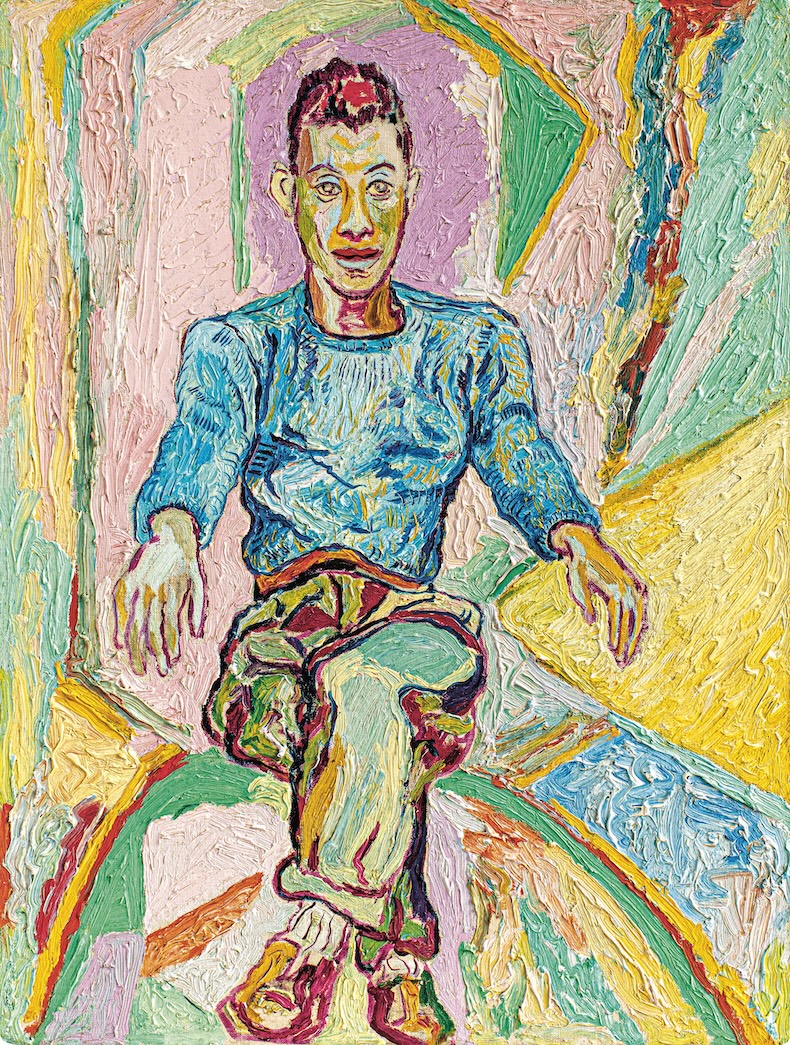

James Baldwin (c, 1945–50), Beauford Delaney. Collection of halley k harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld, New York. Photo: courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York; © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator

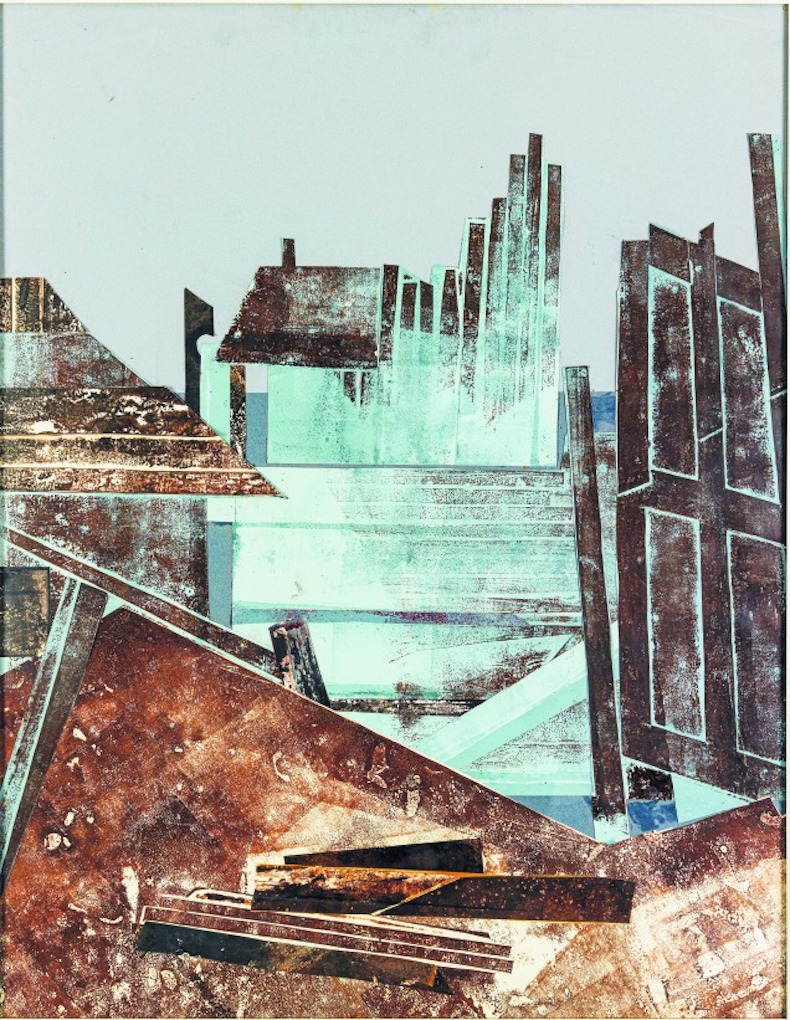

The show is much more successful in introducing Paris audiences to artists they may not have known before. I was delighted to discover the Haitian artist Luce Turnier, who used the photocopier at her secretarial job to create modernist, abstract collages. In the Senegalese artist Iba N’Diaye’s monumental Tabaski, la ronde à qui le tour? (1970), a crowd of sheep wait to be sacrificed for Eid al-Adha, with one animal that has already had its throat cut in the centre of the painting, the blood dripping so realistically to the bottom of the canvas that you almost expect to see a puddle on the floor of the gallery. It is absolutely riveting, containing both the drama of baroque religious painting and the casual messiness of an artist’s sketchbook, with its bubbles of paint and visible brushmarks. Such a challenging, layered piece deserves more space than it has here.

The different rooms orbit around a circular space at the heart of the exhibition, representing the Martinican writer and philosopher Édouard Glissant’s ‘Tout-Monde’ theory, which is never properly explained. I found myself reading Wikipedia pages on Négritude and Maroon art (created by formerly enslaved Africans who had escaped) while walking around the exhibition, wanting to understand in greater detail the cultural thought that ties these works together.

Cabane de chantier (c. 1970), Luce Turnier. Jézabel Turnier-Traube Collection. Photo: © Janeth Rodriguez-Garcia/Centre Pompidou; © Luce Turnier

By the 1970s, the perception of France as a welcoming place for Black artists had largely dissipated. In the febrile atmosphere that followed the student protests of ’68, large-scale strikes over immigrant workers’ living conditions took place. This newfound militancy among the Black diaspora comes through in the art, with protest banners and photos of demonstrations marking this period. This revolutionary spirit was compounded by France’s celebration of the bicentenary of the French Revolution in 1989, which prompted artists to commemorate events such as the Haitian Revolution, when slaves overthrew the French regime at the end of the 18th century. The Senegalese artist Fodé Camara created Parcours n°1 for the ‘French Revolution in the Tropics’ exhibition at the Musée des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie that year, a painting that tells a story from right to left, showing a blur of Black bodies that shed manacles to walk freely, albeit in a red wash of ongoing struggle. One of the contemporary pieces commissioned for the Pompidou exhibition is Regeneration (2025), a four-metre high and 10-metre-wide installation by the French graffiti artist and activist Shuck One, which superimposes Paris street maps on to a huge outline of the African continent, studded with illustrations of Black figures such as Joséphine Baker and Aimé Césaire and newspaper extracts about the May 1967 riots in the artist’s native Guadeloupe. The artist said he wanted to ‘retrace […] a memory of the Black figures who created Paris Noir’ and ‘honour’ them as pioneers.

Untitled (Vétheuil) (1967), Ed Clark. Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer; courtesy Estate of Ed Clark/Hauser & Wirth; © Estate of Ed Clark

‘Paris Noir’ redraws the familiar map of the city, presenting it as a place that has been home to African, American and Caribbean artists for decades. But that is, ironically, also its downfall: the influence of these artists is just too great to be condensed into one exhibition. Hopefully, it will inspire deeper and more precise portrayals of the Paris these figures knew and created in their image.

‘Paris Noir: Artistic circulations and anti-colonial resistance, 1950–2000’ is at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, until 30 June.

Citizen Guillaume – the painter whose fortunes followed the French Revolution’s

Citizen Guillaume – the painter whose fortunes followed the French Revolution’s

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)