From the June 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Patrick Caulfield (1936–2005) was at home in bars and restaurants. More than any other British painter of the post-war period, perhaps, he took up public dining rooms and their attributes – the menu cards, the fondue sets, the companionable wine bottles – and made them his own. After Lunch (1975), that most familiar of Caulfield’s paintings, depicts a waiter surveying a restaurant interior, all pastiche Swiss hostelry, in the stillness following a busy service. It is a cool, calm haven, cut through by a beam of afternoon sunlight.

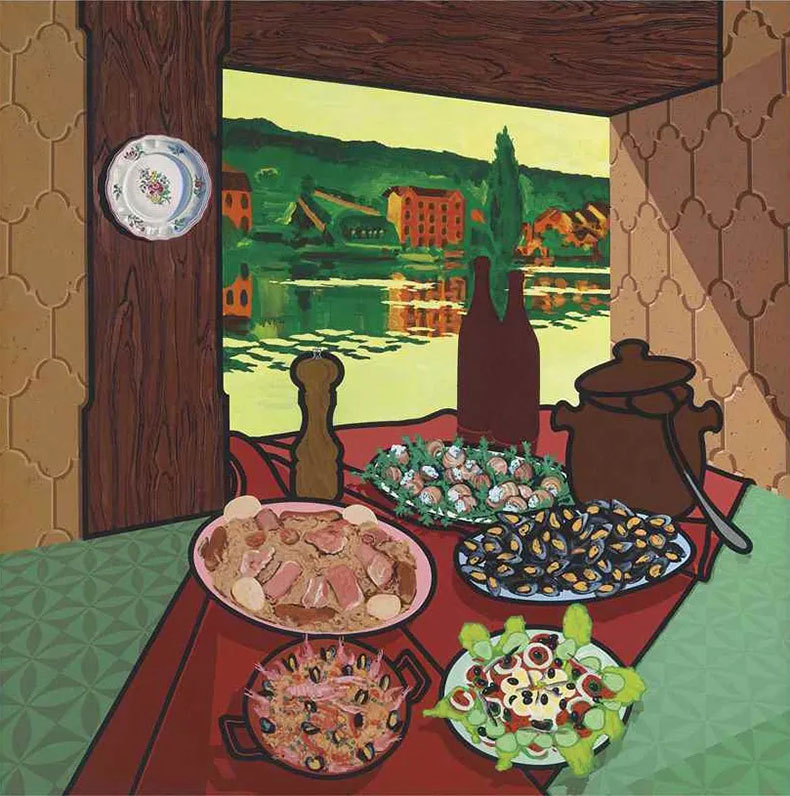

Caulfield and his peers were habitual restaurant-goers, who from the 1960s onwards exchanged their artworks for credit at some of the most fashionable establishments in London. ‘We could have our luxury without paying for it,’ says Pauline Caulfield, the artist’s first wife, recalling how such arrangements allowed for regular meals at Mr Chow’s, Langan’s Brasserie and the Cavendish Hotel, among others. In the 1980s Caulfield ate regularly at Terence Conran’s Neal Street Restaurant, then managed by the Italian chef Antonio Carluccio. For one celebratory dinner Carluccio prepared the array of dishes represented by Caulfield in Still Life: Maroochydore (1980–81) – its fanciful banquet of moules, escargots, choucroute, paella and salade niçoise made to materialise in honour of the artist.

Still Life: Maroochydore (1980–81), Patrick Caulfield. Offer Waterman

The allure of such spaces to Caulfield, not least as prompts for his art, derived perhaps in part from how their convivial glamour contrasted so sharply with the world of his upbringing. Born in East Acton, London, Caulfield moved north with his parents as a boy to the industrial town of Bolton, where his father worked in the De Havilland aircraft factory. ‘The fish and chip shops were the thing,’ he later said. After leaving school at 15, his jobs included a stint in the design department at the food manufacturers Crosse and Blackwell, where his seniors set him boondoggling with tasks that included varnishing chocolates for display.

Restaurants also encapsulated the ordinariness and orderliness, and the coincidence of the mundane and the urbane, that Caulfield came to dwell on in his paintings. ‘One reason I choose restaurant interiors,’ he told the critic Marco Livingstone, ‘is that they give one more scope to introduce space and objects than in a normal domestic setting.’ His restaurants are not actual spaces but imagined rooms, which borrow elements of the observed world to achieve their distinctive atmospheres or moods. They are capriccios of the everyday. In Tandoori Restaurant (1971) the painter expends as much care in rendering the utilitarian ceiling as he does on the room’s ersatz decor and its inviting if implausible depth. Bistro (1970) positions the viewer across a restaurant from a solitary diner, as though proposing that we share his congenial isolation.

It is perhaps surprising to learn, given his attention to restaurants, that Caulfield had little interest in gastronomy – and even more so if we consider the prevalence of food in his paintings. The artist, Livingstone notes, had a ‘famously small appetite’. Caulfield’s wry contribution to SPACE Cooks (2002), an artists’ cookery book, was a recipe for ‘Manhattan Tophat’: a series of bathetic diagrams giving the reader instructions on how to cut a disc from a slice of bread and fry an egg in the cavity.

Instead, food for Caulfield was a means to further his painting. As he began to disrupt his linear style, with its signature black outlines, in the mid 1970s, the depiction of food seemed to pose welcome challenges. In Still Life: Autumn Fashion (1978), for instance, a plate of oysters combines the schematic representation of four shells with a second mode – finely painted, almost photorealistic – for two others. Unfinished Painting (1978) is a well-crafted joke about style and finish. An arm serves a meticulously rendered slice of quiche on to a plate that has been set for the viewer; beyond it the room is represented in Caulfield’s familiar graphic style, and beyond that the painter leaves exposed margins of white primer and unprimed canvas. (‘Patrick really didn’t like quiche,’ says Pauline Caulfield.)

Wine Glasses (1969), Patrick Caulfield. Photo: Ben Westoby Photography; courtesy Josh Lilley, London; © the Estate of Patrick Caulfield. All rights reserved, DACS 2023

Caulfield’s methods of constructing paintings, and how food enabled those processes, are evident in ‘Pass the Peas’, an exhibition of paintings and drawings by the artist at Josh Lilley gallery in London (until 20 June). Caulfield, sympathetic to the condensing strategies of touristic imagery, sometimes painted food from recipe cards that he bought at souvenir shops in the south of France (the dishes in Still Life: Maroochydore derive from such sources). But he also worked on individual objects from life, bringing them into the studio to sketch before wrangling them into paintings – as with the studies of beetroots, potatoes, a steak and a lobster displayed here.

These sketches have an almost ascetic quality, in their abbreviations of forms and volumes. So too does the stylised precision of the study from 1977 for Selected Grapes, an exercise in how far forms might be flattened on the page without crushing them entirely. Here is Caulfield quelling his hunger – but discovering sustenance nonetheless.

From the June 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why it’s time to stop rediscovering Eileen Gray