This show is not just about a single piece of art that combines clarity, wit and profundity – though that would be enough to draw the crowds. The message of ‘One-Way Ticket’, at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, should also humble every visitor with its shocking contemporariness.

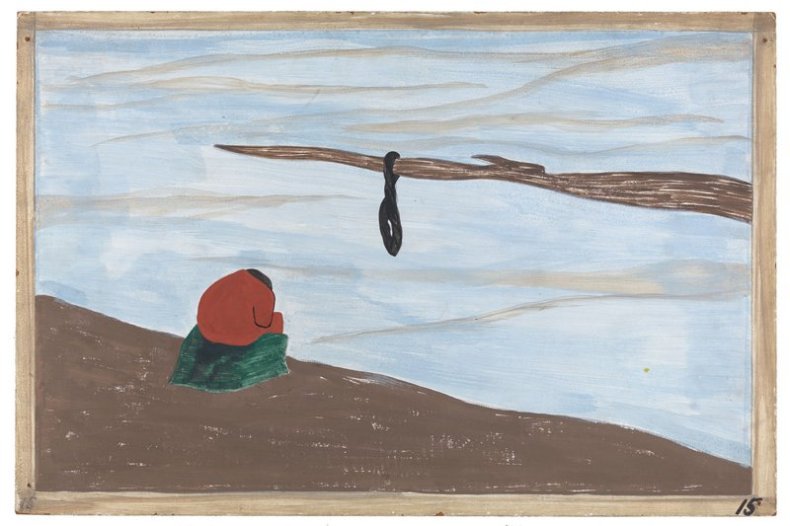

Another cause was lynching. It was found that where there had been a lynching, the people who were reluctant to leave at first left immediately after this. Panel 15 from ‘The Migration Series’ (1940–41), Jacob Lawrence © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph courtesy The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.

This is a rare chance to see the full 60-panel set of Jacob Lawrence’s astoundingly powerful ‘Migration Series’ completed in 1941 when he was just 23 years old. It tells the story of the Great Movement North, when millions of African Americans living in the southern states of the US left for northern ones. Fleeing flood, famine, poverty and injustice, they went to find work (better justice and education were bonuses) in the industrialised cities of Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St Louis and, above all, New York. In 1910 just 92,000 African Americans lived in New York; by 1940 there were 458,000; by 1970 1.7 million. It was one of the largest demographic events of the 20th century.

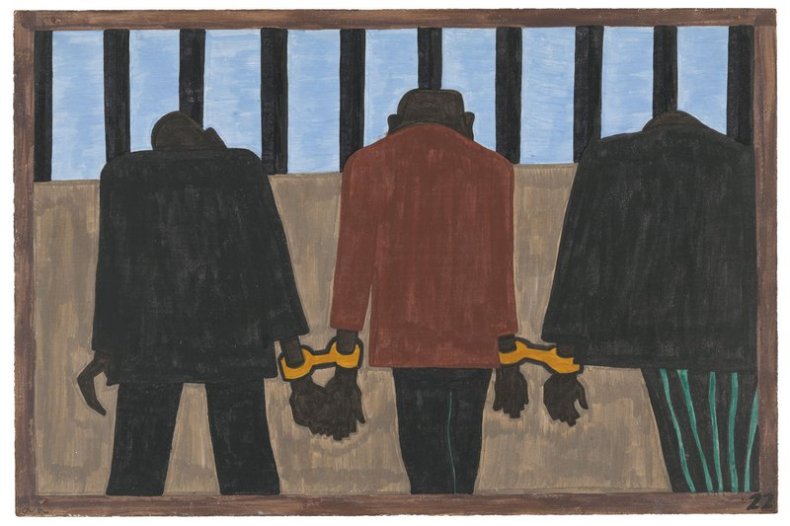

Another of the social causes of the migrants’ leaving was that at times they did not feel safe, or it was not the best thing to be found on the streets late at night. They were arrested on the slightest provocation. Panel 22 from ‘The Migration Series’ (1940–41), Jacob Lawrence © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

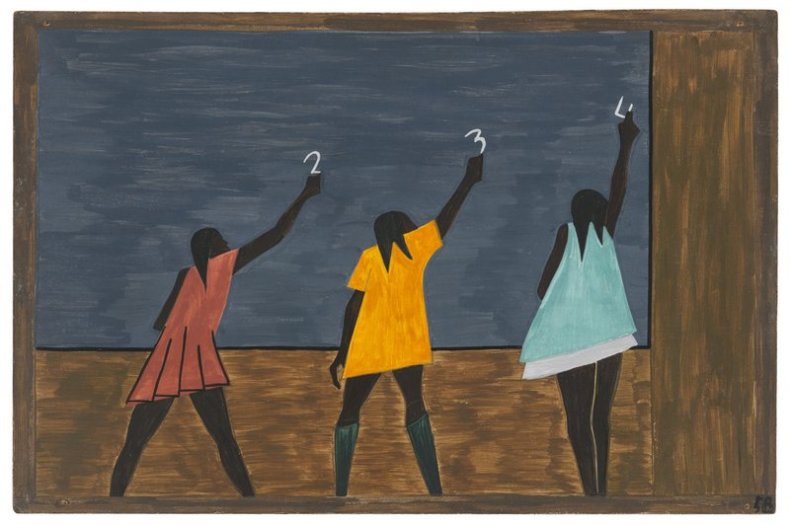

Lawrence depicts the insults, injustices, hardships and hope. He shows with indisputable directness what people left behind – the flooded crops, the lynchings. He shows how they travelled north – the crowded trains, the thousands of miles walked by many families. And he shows what they found when they got there – yes, more food, better education and housing, employment in the steel industry, the freedom to vote, but also prejudice and race riots, a different kind of discrimination. It is this discrimination that will resonate with every person looking at these images today, in light of recent events across the US.

People who had not yet come North received letters from their relatives telling them of the better conditions that existed in the North. Panel 33 from ‘The Migration Series’ (1940–41), Jacob Lawrence © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph courtesy The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.

The paintings have unusual power because they are simple compositions, often seen from unusual viewpoints, painted in areas of flat colour. For coherence, Lawrence worked on all 60 pieces of hardboard at once in a big studio and kept to a narrow palette of Casein tempera paint – a deep green, a bubblegum pink, a saffron yellow, a rusty red. A great storyteller, Lawrence sums up the essence of each event in a bold picture with a one-line caption, doubtless inspired by the news reports he studied at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library: born in the North, Lawrence never made the migration himself.

One of the largest race riots occurred in East St. Louis. Panel 52 from ‘The Migration Series’ (1940–41), Jacob Lawrence © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

When the newly completed series was exhibited at the Downtown Gallery in Manhattan in 1941, the Phillips Collection and MoMA raced to buy it. Neither would give in, so they split it: one got the even numbers, the other the odd ones. Now, all 60 panels and their captions are displayed together in order, strung around one gallery. Adjoining galleries enrich the argument with related literature, music, photography, history and politics. Voices of blues and jazz singers waft into the central gallery; Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs tell of the miserable conditions in the South that stimulated the train ride or walk north; poems by Langston Hughes add poignancy – ‘I pick up my life/And take it away/On a one-way ticket –/Gone up North, /Gone out West,/Gone!’

In the North the Negro had better educational facilities. Panel 58 from ‘The Migration Series’ (1940–41), Jacob Lawrence © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Lawrence told one story with his pictures. Today, they are a loud call to remind us that there is unfinished work to be done for civil rights in the US.

‘One-Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and Other Visions of the Great Movement North’ is at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, until 7 September.

Related Articles

12 Days: Louise Nicholson’s highlights of 2015

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

When the Nazis pilloried modern art