Poring over Basquiat’s notebooks at the Brooklyn Museum feels like flicking through his brain. It’s almost voyeuristic, until you realise that it was always his intention to be famous, to have these very pages displayed, as they are now, as finished works of art.

The 160 pages that make up ‘Basquiat; The Unknown Notebooks’ are not ‘unknown’ in a literal sense: similar pages have been shown in the past. It is the significance of these notebooks that is the real revelation here. The exhibition is not about notes, doodles, or even sketches, but art pieces in their own right.

Basquiat only wrote on the right side of each page, allowing (perhaps hoping) for these notebooks to be taken apart and framed, as they have for this show. However, the exhibition still preserves the rhythm and materiality of the notebooks, with pages placed in low glass cases, encouraging visitors to hunch over the paper, as the artist did. Other works are framed in white and hung along a curved wall to allow for the same sort of sequential view that you might get turning the pages of a notebook.

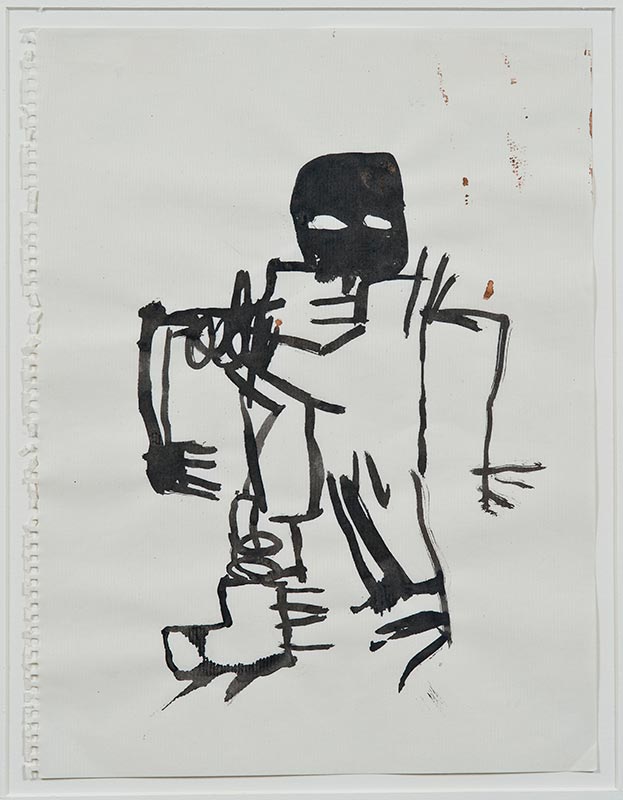

Untitled (Ink Drawing) (1981), Jean-Michel Basquiat © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, all rights reserved. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo: Gavin Ashworth

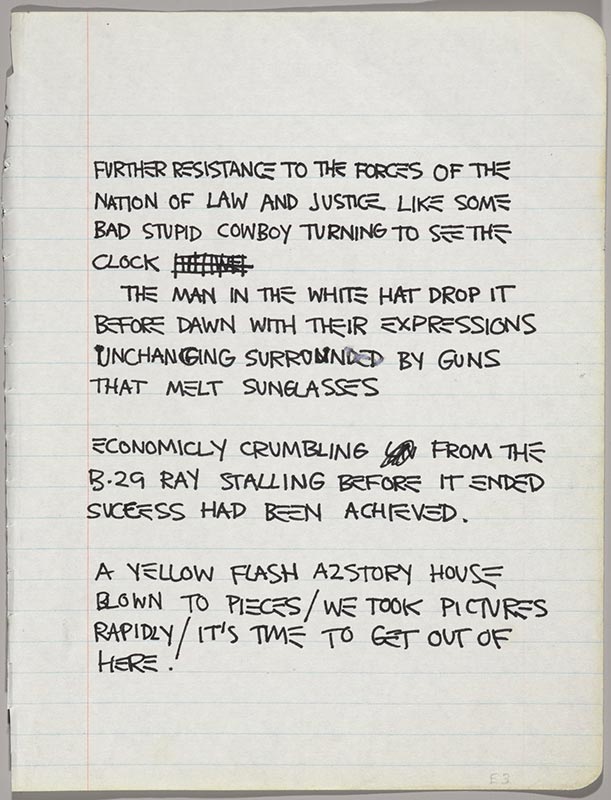

Language was Basquiat’s first medium. At 17 he left home and began spray-painting the streets of Manhattan with critical messages and disjointed poetry. He signed his wordplays ‘SAMO©’, as in ‘same old shit’. The exhibition opens with film clips of the artist making this graffiti; proposing that if Basquiat can paint words onto a wall, shouldn’t he be able to ‘paint’ words in a notebook too? As you watch him spraying phrases like ‘SAMO© AS AN END TO MINDWASH RELIGION, NOWHERE POLITICS, AND BOGUS PHILOSOPHY’ you get the sense that you are watching mark-making, not writing.

Basquiat used words ‘like brushstrokes’, painting with all his senses, not just for their meaning but also for their sound and look. He developed a sort of personal hieroglyph, which persisted throughout his works. He reduced the letter ‘E’ to three horizontal lines and always used block capitals, beginning each letter anew. He would repeat letters for a rhythmic, ornamental effect, often embellishing words with purposeful misspellings or crossing them out.

The graphic element of these phrases by no means suggests that they are without meaning. They illustrate Basquiat’s restless originality, irony, playfulness and bite. It was this youthful vitality that propelled him onto the art scene in 1981 and fuelled his short career until he passed away from an overdose in 1988 at only 27.

Untitled Notebook Page (1980–81), Jean-Michel Basquiat © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, all rights reserved. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo: Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum

Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition encourages you to ‘get to know’ Basquiat by picking at every detail. Curators Dieter Buchhart and Tricia Laughlin Bloom almost challenge you to a game of ‘Where’s Waldo’, using laminated maps of the marks on large painted works such as Untitled (1986) to point out references to pop culture, literature, celebrity, and music. However, this ‘de-coding’ of long stretches of small pieces of paper can become tedious, making the show feel like a diehard Basquiat fan club, fetishising his every scrawl and scribble.

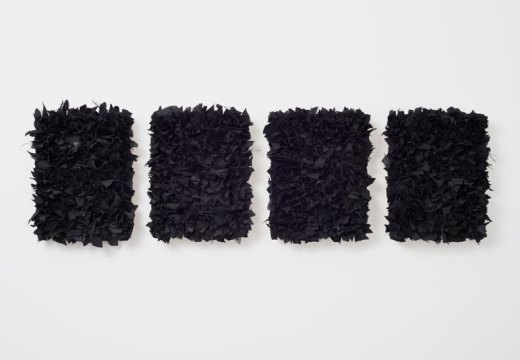

The format of the ‘composition book’, which Basquiat used exclusively for his notebook series, became his own golden ratio. To transfer its aesthetics to his other works, Basquiat went so far as to directly Xerox and collage its pages onto his pieces. He consistently returned to its proportions in larger works, such as his painting, Untitled (Ideal) of 1988, and his wood box, also Untitled, of 1985 – both of which sit opposite the pages, inviting comparison.

As you muddle through the joyful chaos of these notebooks, Basquiat’s daily life and thoughts become tangible. It is easy to imagine him filling these pages, consuming, discarding, binding and recombining the conversations, images and slogans he gleaned from the city. Throughout the exhibition, as letters morph into motifs, it becomes clear that these are not sketches – they are drawn words.

‘Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks’ is on view at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, until 23 August.

Related Articles

‘Now’s the Time’: Basquiat’s work at the Art Gallery of Ontario is still relevant

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)