From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

This year began with the announcement of another artefact from a UK museum being returned to its country of origin. After detailed provenance research, pointing to the object being looted from a temple in Tamil Nadu in 1957, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford received permission from the Charity Commission to repatriate the 16th-century bronze statue of Saint Tirumankai Alvar to India. The successful transfer highlights the contradictory state of the restitution debate in Great Britain: on the one hand, a quickening rhythm of returns from university and regional museums and on the other, continued confusion around deaccessioning contested objects from national collections such as the V&A and British Museum. It is going to take a clear, political decision to end what, for national museums, is debilitating stasis.

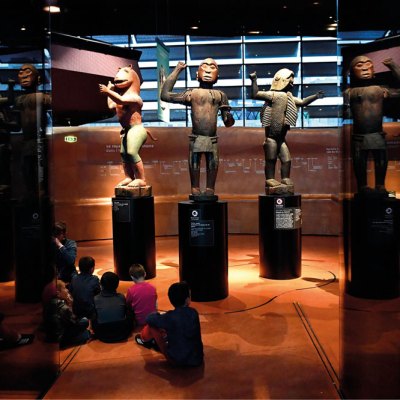

An increasing number of museums, which are not encumbered by prescriptive legislation on restitution, are engaging in creative ways with source communities around the world. Among the returns of recent years, one could highlight the successful transfer in 2022 of the ownership of 12 Benin Bronzes, along with other items looted by British forces in 1897, from the Horniman Museum and Gardens in London to Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments. Six of the bronzes were physically relocated to Edo state, while the rest remain in the same vitrine but, crucially, are now on loan to the south London museum.

A 16th-century bronze depicting Oba Orhogbua that was owned by the Horniman Museum in London until November 2022, when it was restituted to Benin City. Photo: © National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria

In Edinburgh, the National Museum of Scotland has permanently ‘rematriated’ a memorial pole to the Nisga’a Nation of Canada. Trinity College, Cambridge has returned a set of spears, taken by sailors during Captain Cook’s landing at Botany Bay, to La Perouse and Gweagal Aboriginal communities. Manchester Museum has returned 174 objects to the Anindilyakwa community in northern Australia. The Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery in Exeter has restituted a ceremonial headdress, bequeathed by a former Lieutenant Governor of the Northwest Territories, to the Siksika Nation in an official handover in 2024.

In a scholarly and professional manner, UK museums are leading much European practice when it comes to repatriation. Some clearer policy guidance around restitution from Arts Council England (ACE), as well as a more sympathetic stance from the Charity Commission – which often has to sign off the trustees’ decision to transfer collections – has certainly helped.

Even those museums unable to deaccession are finding innovative ways to share collections more equitably. At the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), we have pursued renewable cultural partnerships with museums across source nations, allowing for the long-term loan of materials. In Turkey, the V&A has collaborated with the Istanbul Archaeology Museum to reattach the head to a baby Eros sculpture, from the 3rd-century Sidamara sarcophagus, which had lain in the South Kensington stores for 90 years. In Ghana, we partnered with the British Museum to return significant Asanti treasures looted from the Royal Palace during the storming of Kumasi in 1874. These partnerships form the basis for long-term relationships involving scholarship, curatorial and conservation exchange, as well as education programmes.

King Osei Tutu II leads a ceremony in Kumasi, Ghana, in May 2024, celebrating the return of gold regalia to the Asante kingdom. Photo: Ernest Ankomah/Getty Images

But the retort, from understandably indignant politicians in source countries, often comes back: ‘Why should we borrow from you the stuff you stole from us?’ The answer is the 1983 National Heritage Act (an updated version of the 1963 British Museum Act), which prevents deaccessioning from certain national museums. In strict legal terms, the Act permits trustees to dispose of an object only if it is a duplicate; has become ‘unsuitable’ for the collections; if it is transferred to another national museum; or it has become irreparably damaged.

The two exceptions to this law are objects covered by either the 2004 Human Tissue Act – which concerns human remains less than 1,000 years old – or the 2009 Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act. Under the latter, on a case by case basis, after the judgement of the Spoliation Advisory Panel, UK museums are obliged to return artefacts lost by their rightful owners (and heirs) due to Nazi persecution. In 2014, the V&A, for example, complied with a ruling to return a set of Meissen figures to the heirs of the Hamburg-based Jewish collector Emma Budge, whose art holdings were ‘auctioned off under duress’ by the Nazis in 1937. Increasingly, however, the question is being asked: what is the moral difference between Nazi and colonial looting, and should there not be a commensurate process of returns?

Last year the UK Charity Commission authorised the return to India of this 16th-century bronze in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Photo: Ashmolean Museum

For this and other reasons, the 1983 Act is outdated and infantilising: trustees should have autonomy over their collections, which includes the right to deaccession (especially as the financial and carbon costs of storage grow ever larger). The original intention of the Act – to prevent wilful museum directors jettisoning ‘unfashionable’ holdings – now fails to take account of the ethical context in which historical collections have accumulated, and the moral framework that informs international partnerships.

None of this is to disavow the purpose of the global museum – most especially at a time when the forces of nativism and chauvinism are so gruesomely on the ascendant. In multicultural European cities with large diasporic populations, it is vital that galleries display the rich culture of different peoples and communities, and work to explore commonalities with any perceived ‘Other’. In this context, the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah has rightly warned of the dangers posed by those counter-cosmopolitan critics to the encyclopaedic museum, ‘conflating universality with imperialism’, who ‘would make these institutions more parochial, less humanly expansive, less diverse – and all in the name of an incoherent and parochial concept of cultural property’.

Balancing equity with the Enlightenment purpose of museums, there is a pathway forward focused on provenance research, respectful collaboration and institutional humility. There is also now an obvious legal solution. Sections 15 and 16 of the Charities Act 2022 – stay with me – authorise museums to undertake ‘ex-gratia’ disposals where trustees conclude a ‘moral obligation’ exists. This technical legalese, hidden away in an obscure act, could finally cut the Gordian knot of the British restitution debate and free trustees to deaccession highly contested objects.

Realising its implications, the previous Conservative government, fearing a row during a general election over the loss of the Parthenon Marbles to Greece, specifically excluded national museums from this provision. But under a new government with a more internationalist outlook, there is an obvious opportunity to enact these laws. As Alexander Herman, director of the Institute of Art & Law, puts it: ‘this small and straightforward step would help museums build bridges with countries and communities of origin, an important part of their ethical best practice today.’

It would also be wise to follow the best practice of our European colleagues in establishing some legislative oversight (beyond the Charity Commission) for restitution cases. In Holland, the Colonial Collections Committee advises on requests for the return of cultural goods ‘which were brought to the Netherlands in a colonial context.’ In Ireland, there is a new expert committee on the restitution of ‘historically and culturally sensitive objects’. Even Switzerland has inaugurated an ‘Independent Commission for Historically Contaminated Cultural Heritage’, looking at both Nazi and colonial-era objects. In the UK, our own Spoliation Advisory Panel provides an excellent precedent for overseeing decisions on the return of objects.

Such a significant change to UK museum policy should not take place without a public debate. Thus far the Labour government has been fairly silent on the question of restitution, apart from the traditional Downing Street refusal to countenance any change to the law, and culture secretary Lisa Nandy’s rather gnomic desire for a ‘consistent’ policy across museums. But now is the time for political leadership: the international community expects it, the legal tools are available and a decision needs to be made.

Tristram Hunt is the director of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.