From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The Spoliation Advisory Panel (SAP) deals with claims for the restitution of works of art looted by the Nazis between 1933–45 and held in public collections in the UK. Would a similar body be suitable for assessing artefacts that are said to have been looted during Britain’s colonial past? I do not come at the subject with specialist expertise, but my experience as a claimant before the SAP has set me thinking. What follows is not meant to be prescriptive, but an outline in principle of how such a process might work, and what lessons can be learned from the work of the SAP.

‘Looted’ is a contested term: it covers a spectrum from out-and-out pillage to ostensibly legal transfers of title that may have occurred under coercion or under rigged laws. Britain’s art and ethnographic museums hold items that may fall into either category: not just West African artefacts or the Parthenon friezes, but a host of precious or sacred objects collected during the colonial era from across the globe. More attention than before is now given to whether they should be retained or returned: the proposal here is for a method to evaluate claims that has legitimacy in the eyes of claimants, institutions and the public.

The SAP was set up in 2000, and is now governed by the Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act 2009. It recommends to the UK culture secretary (or Scottish ministers) whether to order restitution of objects in the possession of a UK national collection or another UK museum or gallery established for the public benefit. The Act permits 17 institutions, including the Tate, the British Museum and the National Gallery, to override bans on deaccessioning when the minister approves the SAP’s recommendation. For example, in 2014 the SAP recommended that the British Library return the Biccherna Panel (a 15th-century painted wooden panel that was used to encase tax records in the treasury of the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena) to the descendants of its Jewish owners, who had been forced by the Nazis to sell it in 1936 (in the event, the claimants accepted compensation in lieu of restitution). The SAP may also recommend monetary compensation, ex gratia payments, or merely that the history and provenance of the object is publicly displayed alongside it. The SAP has reported on some 20 applications since its foundation. To date, the secretary of state has accepted all of them.

As an ‘advisory non-departmental public body’, the SAP is independent from government, though its members are appointed by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). They have backgrounds in law, the civil service, academia, the art world and cultural institutions. Each is distinguished in their own field. Their recommendations have no legal force (the SAP is not a court), but it considers both the legal and – more problematically – the moral aspects of restitution claims. The proceeding is similar to a court case, with the panel scrutinising evidence and weighing up the arguments on each side before it makes its decision and final recommendation on the balance of probabilities. The relatively straightforward legal aspect includes issues of title and ownership, though these can still be difficult where provenance records are lacking or are disputed.

The claimants to the SAP have been the heirs and descendants of the original owners. The concept of ‘restitution’ may be less straightforward in the colonial context. There may be no readily ascertainable line of ownership. A community from which a precious artefact was taken may have broken up; borders may have been redrawn so that its place of origin is another, even a hostile jurisdiction; communities may have complex relationships to current national governments or nation states. Who has standing to claim it in such circumstances, and what would ‘restitution’ mean? The consideration of such questions would necessarily bear on the establishment of any new panel.

In deciding the moral weight of a claim, the SAP’s terms of reference require it to ‘take into account non-legal obligations, such as the moral strength of the claimant’s case’. This, in my view, is where the real difficulties begin.

My family made a claim to the SAP in 2009, for a painting which belonged to my German grandfather. He sold it at an auction in 1934, together with the rest of his art collection. He had been the object of anti-Semitic propaganda before the Nazis took power in January 1933, after which the bank of which he had been a director was rapidly ‘Aryanised’. He soon lost his remaining positions and income. We maintain that the Nazis who took over the bank abused due legal process to make him personally liable for debts owed by the bank, and in an act of financial persecution forced him to raise the money by selling his collection. In its report, however, the panel found that, despite evidence that he was targeted for persecution as a Jew, the debt was a normal commercial debt, not tainted or not sufficiently tainted to make a moral case for restitution.

The SAP’s approach has not been followed by institutions in Germany and Austria, which have voluntarily returned items auctioned in the same sale; and in 2020 the SAP’s equivalent restitution committee in the Netherlands found in our favour in respect of a collection of porcelain, also from the 1934 sale, now held in several private and public Dutch museums.

The difference in approach shows up the difficulty in determining what constitutes a sufficient moral case. It may be that countries that have experienced Nazi rule have a more sensitive moral compass than the UK. The SAP’s strength is its close forensic attention to the evidence, but arguably at the expense of an underlying principle as to what constitutes a strong moral case. For example, in a claim brought against the British Museum for the restitution of items auctioned in Berlin in 1939, it found in a 2012 report that:

Having concluded on balance that this was a forced sale, the Panel, nonetheless, considers that the sale is at the lower end of any scale of gravity for such sales. It is very different from those cases where valuable paintings were sold, for example, in occupied Belgium to pay for food or where all assets had to be sold in Germany in the late 1930s to pay extortionate taxes. The sale was not compelled by any need to purchase freedom or to sustain the necessities of life. Furthermore, the sale was arranged by a prominent English auction house with (so far as we can tell) no cause to question the seller’s reasons for selling.

So the sale was forced, but not forced enough for restitution. It seems to me that this approach is too narrow and legalistic, and fails fully to recognise the reality of existence for Jews in Hitler’s Germany, where destitution, violence, imprisonment and death were a constant, immediate threat. Two months after he sold his art collection, my grandfather was arrested by the Gestapo on the Night of the Long Knives in June 1934, and was lucky to be released after a few days. He fled Germany for the UK, a broken man, two years later.

However, the existence of an independent panel to make recommendations, and all but in name to adjudicate these claims, has distinct advantages. It relieves the institutions themselves from being judges in their own cause, making controversial decisions about issues in which they have a protective interest. As a disappointed claimant I may have complaints about a decision, and criticism of the opacity of the ‘moral case’ dimension of the process, but in general the SAP is capable of producing fair decisions. The process has credibility.

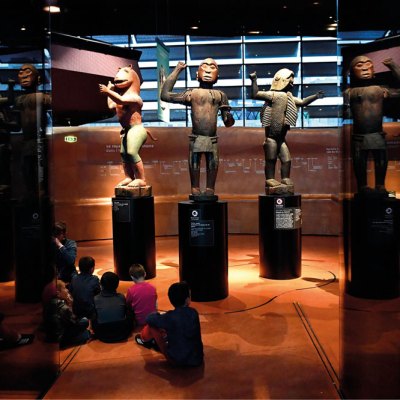

Can a version of the process be used in other restitutions, outside the Nazi era? As institutions have become more attuned to the violent or coercive provenance of some colonial-era artefacts, the question of what to do with such items becomes more urgent. Circumstances vary, from the ostensibly legal purchase by Lord Elgin of the Parthenon marbles in the early 19th century to the shameless plunder of the Benin Bronzes in 1897.

The SAP’s remit is historical, and limited to a single period. The UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property 1970, by contrast, requires states to take action against the ‘illicit import, export and transfer of ownership of cultural property’ (broadly defined) that may have occurred since the convention came into force. It recognises that this ‘is one of the main causes of the impoverishment of the cultural heritage of the countries of origin of such property’. The actions required are prevention, restitution and international cooperation. An intergovernmental committee ‘seeks ways and means of facilitating bilateral negotiations, promoting bilateral and multilateral cooperation, with a view to the restitution or return of cultural property, as well as fostering public information campaigns on the issue, and promoting exchanges of cultural property’.

There is no equivalent international convention for the identification and return of ‘cultural property’ that was wrongfully removed before 1970, or in the colonial era. The historical removal of such artefacts generates deep emotion and anger, as the curator Dan Hicks expresses in The Brutish Museums (2020), in which he examines the murderous looting by British soldiers of Benin City in 1897, and its aftermath. Hicks gives less attention, however, to the process to be adopted in deciding whether and how to make restitution – the nuts and bolts. He argues that no museum is entitled to keep the Bronzes; doing so is itself a perpetuation of the violence done by the soldiers. More broadly, he believes that ethnographic museums were and still are complicit in acts of brutality. Benin may well be an egregious case that demands no answer other than restitution. Nonetheless, there must be a credible and principled process by which the desire for a particular restitution is given effect in each national jurisdiction. Righteous, justified anger alone does not answer all questions that arise in all cases. The process must be fair and must be seen to be fair.

Institutions in Europe have been active in re-evaluating their holdings, but not consistently. The Dutch ethnographic museums (collectively the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen) have appointed an independent panel of advisers to consider restitution issues. In France, following the Sarr-Savoy report of 2018, Emmanuel Macron has advocated restitution of objects taken from former colonies, some of which the Musée du Quai Branly is now in the process of returning – in the face of vocal opposition, including from its longstanding former director. The Humboldt Forum in Berlin has removed its Benin treasures from its yet to be unveiled public display and intends to return them. An independent panel of experts in Belgium, however, has criticised the government for failing to deal with items looted from its empire in central Africa. In the UK, the Horniman Museum has set out a procedure through which it would voluntarily part with its Benin pieces.

A museum-by-museum approach is one way forward. The risk is that if separate museums make their own decisions or have their own panels, they may give inconsistent decisions when dealing with comparable issues. If that happens, the process will lose credibility. I would suggest that a commission of experts is established in the UK, empowered to consider restitution claims relating to objects removed from their place of origin during the colonial era. An institution could refer itself to it, or it could hear claims from interested parties. If its structure was based on the SAP, the decision whether to act on its recommendation would be made by the secretary of state, so legislation would be required to set it up. (An institution would not necessarily be prevented from offering voluntary restitution, but something equivalent to the provision in the 2009 Act would be needed to override the ban on deaccessioning, with exceptions for duplicates and damaged works, that applies to the big national institutions.) But independence from government, museums and claimants should be its priority. It would draw on a wide range of skills and experience in the UK and internationally. It would need to draw on specialists who are knowledgeable about each case: and its decisions would be highly case-specific. It might face the charge that it represents a new form of colonialism, in that it would be constituted and consider claims in the UK: it could refute that by being impartial, evidence-based, independent and fair to all concerned. One way to do this is to refine the ‘moral case’ aspect of restitution claims, by for example introducing a rebuttable presumption that items removed by force, or purchased at a significant undervalue, or under coercion, ought to be restituted.

It will take time and patience for the full investigation and evaluation of a claim. Decisions should not be reactive. There should be no rush to judgement. There may be no universally acceptable method of resolving grievances over this aspect of the UK’s colonial past, but one that relies on evidence, reason and expertise should command respect.

Francis FitzGibbon is a QC. He is a regular contributor to the London Review of Books.

From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.