From the December 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

These days The Americans by Robert Frank (1924–2019) is hailed as a classic photography book. But when it came out in the United States in 1959, a year after its initial publication in France, it met with suspicion and scorn. The texts that accompanied it – by the likes of Simone de Beauvoir and Henry Miller – were deemed too downbeat and were left out of the new edition; no doubt the introduction by Jack Kerouac – ‘He sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world’ – added to the suspicion that this was an anti-patriotic project. Visually too it attracted brickbats: Popular Photography complained it was a ‘meaningless blur’, little more than ‘muddy exposures, drunken horizons and general sloppiness’.

Over time The Americans began to exert a gravitational pull. Ed Ruscha, who chanced upon a copy in a college bookshop, liked to recall the effect it had upon him: ‘I realized this man’s achievement could not be mined or imitated in any way, because he had already done it, sewn it up and gone home.’ Another admirer was the young Jeff Wall and he too felt that Frank’s photographs, though ‘awesomely perfect’, represented a kind of terminus: ‘I realized that I couldn’t do anything that they hadn’t done. It was just pointless.’ Famously – and, to some, confoundingly – Frank himself was eager to move in other directions. What, he began to ask himself, could single images achieve in an ever more media-saturated culture? Wasn’t the decisiveness they sought to capture out of step with the speed and flow of modern life?

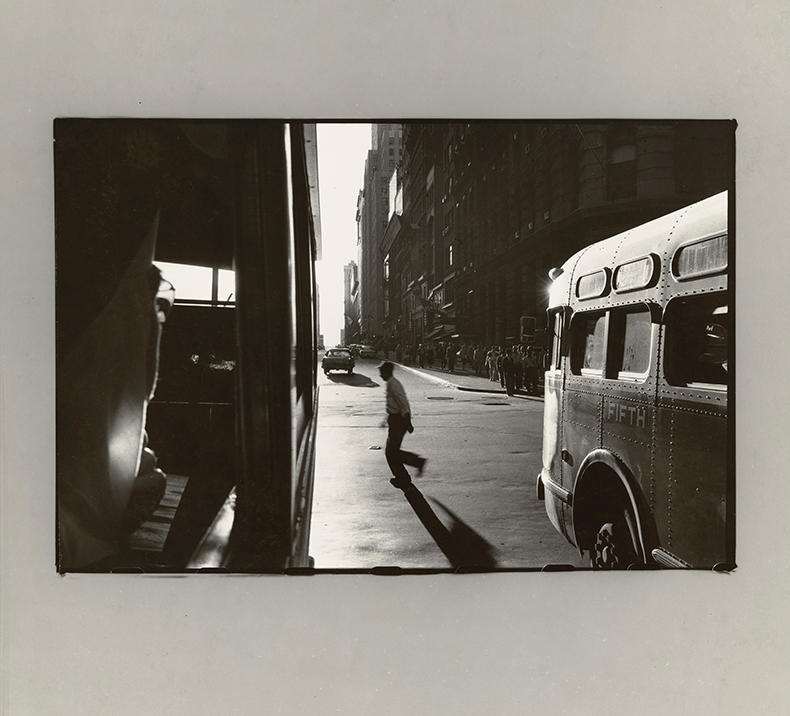

From the Bus, New York (1958; detail), Robert Frank. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

‘Life Dances On’, the first exhibition devoted to Frank’s work at MoMA, and staged to mark the centenary of the Swiss-born photographer’s birth, tracks the directions he pursued in the wake of those doubts. At first, there is continuity rather than change. In the series From the Bus, New York (1958) Frank peers out at the streets of pre-downturn Manhattan, singling out a pedestrian who is strikingly isolated as he crosses an intersection. He is faceless, casts a long shadow, wears a cap that could be that of a janitor. Though his shirt is tucked in, he looks enfeebled, barely present. Beyond him, a sidewalk: it’s busy but far from teeming; the men seem to have been stunned. Other images show a hand hanging out of a window, a tired removal-company worker leaning against a van, a moody toy vendor.

Another series – Fourth of July, Coney Island (1958) – is also an exercise in brooding detachment. This is far from the thronged pleasure grounds of Weegee – midday sun, tens of thousands of half-clad revellers, so busy the sand can barely be seen. Frank’s photos speak of dawn, twilight, darkness. Couples lie on the floor, surrounded by bottles and loose clothing, their bodies coiled and contorted so that they themselves resemble abandoned goods, human flotsam. In one black-and-white image, the sleeping bodies look stricken, irradiated – not least because the Parachute Jump amusement ride behind them looms ominously, like nothing so much as a mushroom cloud.

Frank found new possibilities by hanging out with beatniks and the emerging downtown New York scene. The MoMA exhibition includes clips from Pull My Daisy (1959), a jazzy, chaotic film he made with Alfred Leslie, which featured a motley bunch of bohemians (among them Gregory Corso, Larry Rivers and Delphine Seyrig) falling about a Bowery loft while a voiceover by Jack Kerouac asks ‘Who are poets? Are we all we poets?’ There are photos of a happening initiated by Claes Oldenburg, a script for an (unrealised) film version of the poem Kaddish on which he and Allen Ginsberg collaborated, cover art for the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street LP. It’s a long way from his Picture Post-redolent portrait, taken in 1951 and also featured in the show, of a Welsh miner drinking a cup of tea.

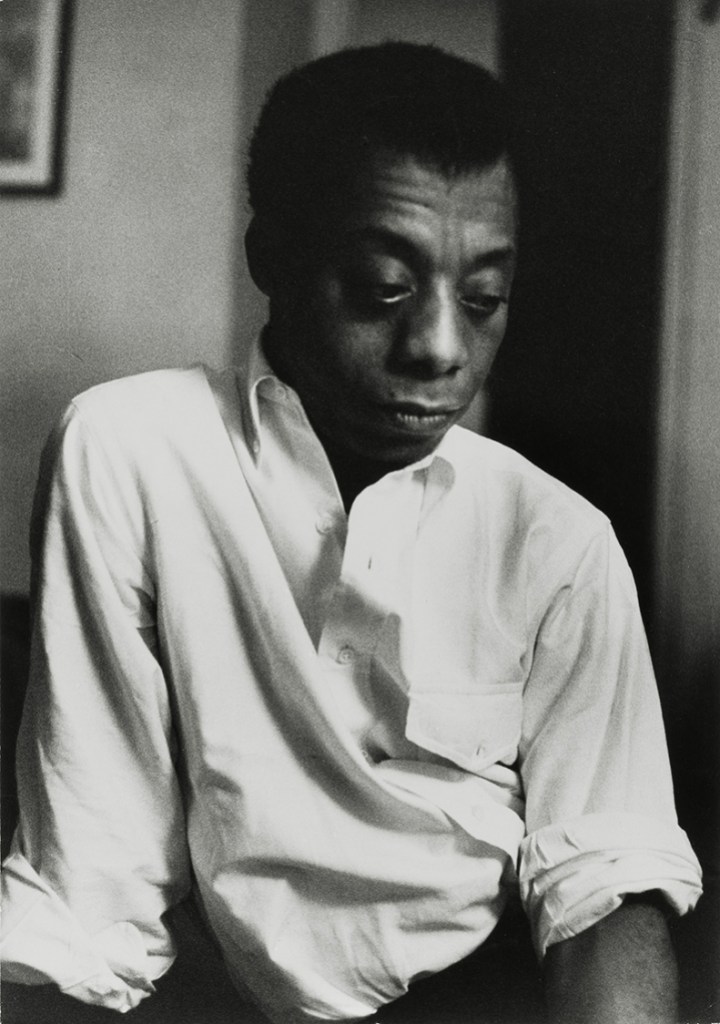

James Baldwin (c.1963), Robert Frank. Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

These artists – their energy, their impulse to abstraction – gave him a licence to roam, to trust his own intuition. Through the 1960s he still accepted commissions for magazines such as Mademoiselle and Harper’s Bazaar, shooting public figures such as James Baldwin and Norman Mailer, but his main focus was film-making – most notably Me and My Brother (1965–68) and Life-raft Earth (1969). This latter short, featuring Whole Earth Catalog founder Stewart Brand, provides evidence of his growing environmental consciousness.

In 1971 Frank moved to Mabou in Nova Scotia and many of the show’s most powerful images are of this wet, often snow-sealed terrain. They are smudged, aching. Grey seas, cloud-streaked skies, scant vegetation. Life is not dancing here: it is stilled, exilic, posthumous even. It’s impossible to look at them without thinking about the savage bereavements he experienced – in 1974 his daughter Andrea was killed in a plane crash; his son Pablo died in 1994 after a long struggle with schizophrenia. ‘So many things in life, if life is ended and it’s never going to be there again, it makes you strong to remember,’ Frank said. ‘Especially in Mabou. I think a lot about a life ended like that.’

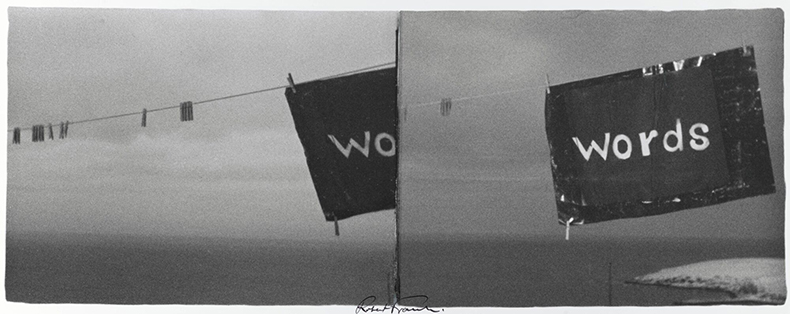

Andrea (1975). Museum of Modern Art, New York

On his 30-state road trip across America in the 1950s, Frank had captured isolation, semi-detached citizens, a benumbed alienation that ran counter to the feel-good stories peddled by ad-men and master planners. Twenty years later, with the economy floundering and the atrocities in Vietnam weighing heavily on the nation, that melancholic iconography appeared prescient. At MoMA the walls become increasingly grief-wrecked: photos are stitched together to create unstable landscapes; images are scratched and scribbled upon (‘time and tide waits for no man’; the word ‘fear’ above a shot of a typewriter perched by a window overlooking a shingly beach); the maquettes for his many artist books (which he called ‘visual diaries’) are hushed, haunting. Now, at the end of 2024, after an election that has left half of America feeling estranged and disconsolate, ‘Life Dances On’ is profoundly englooming, a slow wake.

Mabou (1977), Robert Frank. Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2023 June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

‘Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue’ is at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 11 January 2025.

From the December 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze