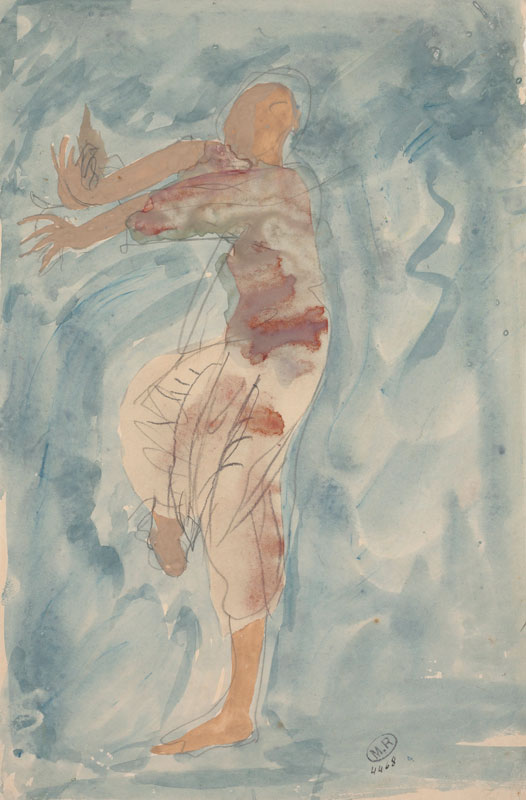

The focus of this perfectly realised exhibition is a collection of small terracotta and plaster figures, created by French sculptor Auguste Rodin around 1911, at the very end of his career. These figures were never exhibited in his life time and were only cast in bronze posthumously. They were made using a small set of moulds for the different parts of the body, the casts of which Rodin would arrange together (differently each time) and roughly finish by hand. Each dancer is shown in a particular extreme but graceful dance posture, at the edge of human flexibility and just before acrobatic virtuosity becomes grotesque. Separately, the bits of limb and torso look like so many spare parts from a toy workshop. Put together, however, the individual figures have an exhilarating humanity about them. They are known collectively as Mouvements de Danse.

Dance Movement C (1911), August Rodin. Musée Rodin, Paris, France

In the words of the great American critic Leo Steinberg (quoted in the excellent catalogue), despite the figures being ‘so frankly made of crude rolls of clay of nearly uniform thickness…they dance. Accepting perfunctory surfaces and awkward limbs, they are oblivious of self and body, of style and beauty – to be only what the dance is.’ They seem to express the revelation that we are our bodies – and that through dance, liberated from the constraints of conventional ballet, we can discover new possibilities of both body and spirit.

Cambodian Dancer in Profile (1906/07), Auguste Rodin. Musée Rodin, Paris, France

The show pivots neatly around a single moment. In 1906, in his mid sixties, Rodin witnessed a performance by the Royal Ballet of Cambodia in Paris. A major figure by now, he was quoted by journalists saying ‘The Cambodian dancers have revealed movements to me that I have never found anywhere before, either in the art of sculpture or in nature.’ He added, ‘For my own part, I know that in watching them my vision has expanded: I have seen higher and further; I have learned something.’ So inspired was he, that he negotiated to travel with the dancers to their next stopping place in Marseille. In the first room, we see the delicate ink, pencil and gouache drawings he made of the dancers, capturing with fleeting and fluid gestures the precise energy of their movements – the ripple from the end of one arm, along the shoulders to the other, which he so admired, or their hyperextended wrists and hands. As he said at the time, ‘all the movements of the body, if they are harmonious and right, can be inscribed within a geometric pattern whose lines are simple and few.’ These drawings, although not conceived in relation to any new work, laid the foundation for the Mouvements.

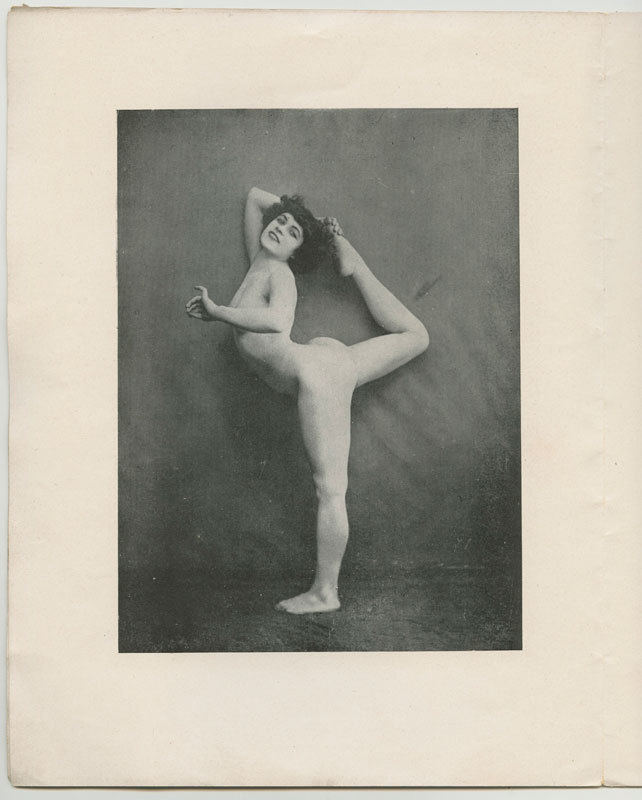

Le nu académique journal of 1905 showing the newly discovered photos of Alda Moreno in the pose of ‘Dance Movement A’ (30 June 1905). © Agence photographique du musée Rodin – Pauline Hisbacq

Rodin’s interest in dance was not new. Since the 1890s he had focused – like Stéphane Mallarmé and other friends and colleagues – on its potential as a language akin to poetry. Photographs in the Rodin archive of avant-garde luminaries such as Loïe Fuller, Isadora Duncan and Ruth St Denis, and groups of drawings of Japanese actress Hanako and the acrobatic dancer Alda Moreno testify to Rodin’s continuing fascination with the expressive potential of dance movements. Exotic and experimental contemporary dance was a major cultural phenomenon in France, and a significant thread within modernism which gave birth to Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes (1909–1929). Indeed, the only additional sculpture on show here is the extraordinarily potent, tiny leaping figure Rodin made of Vaslav Nijinsky, after seeing him perform his scandalous masterpiece, L’après-midi d’un faune, in May 1912. Rodin’s fascination with dance opened new possibilities for his sculpture. As Juliet Bellow expresses it in her groundbreaking catalogue essay, Rodin’s interest extended beyond movement to a fascination with ‘the body’s relation to its spatial envelope, to the pull of gravity, and to the enactment of stillness’. The innovations he so admired in dance dovetailed, she suggests, ‘with the most radical dimensions of Rodin’s sculptural practice.’

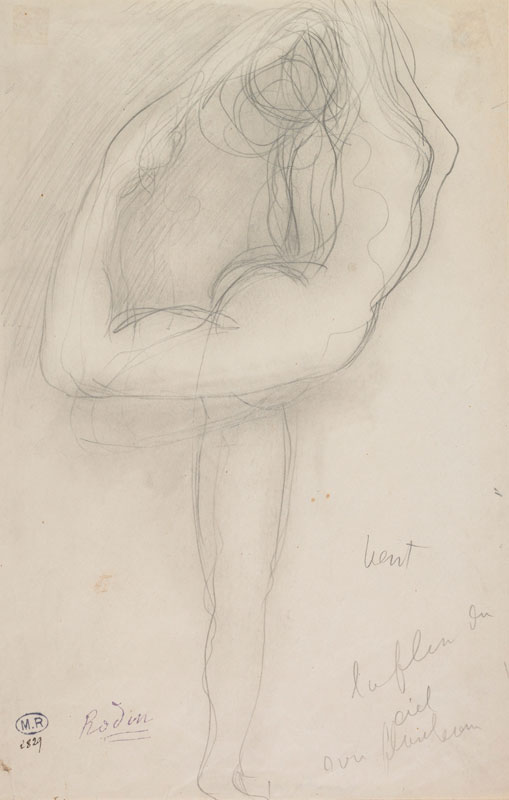

Standing Nude Holding Her Right Leg (c. 1903), August Rodin. Musée Rodin, Paris, France

In the main room of the exhibition, the models at the centre are ringed by a selection from the hundreds of drawings Rodin made from 1900 onwards of dancers in a variety of extreme poses. There is a thrill of analytical precision about these works. Count Harry Kessler, a German collector and patron who was allowed to see a portfolio of them in 1912, remarked: ‘…it’s almost pure mathematics. It’s not driven by passion, or rather, it looks like the movements of unknown passions, which we can’t imagine but might be possible – passions that are not human.’ But the drawings do have a passionate, even erotic urgency, often featuring the genitalia of his nude models in the middle of the sheets. It is as if, through these drawn and modelled movements, Rodin felt he could grasp at something essentially human. For as he put it himself, years later, writing about Cambodian and Javanese dancers: ‘[Their dances] are ordered like architecture: mathematical laws govern them. What profound emotion in the dances of the little Javanese!’

‘Rodin and Dance: The Essence of Movement’ is at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until 22 January 2017.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)