Roger Moore’s most accomplished performance was undoubtedly playing himself. As a lavish new documentary makes clear, ‘Roger Moore’ was an invented persona, one developed by the actor as he progressed from a childhood in south London to Hollywood A-list status, an army of celebrity friends and an international brood of children from his four marriages.

From Roger Moore with Love is narrated by the beyond-the-grave voice of Moore himself, which is in fact Steve Coogan doing his best impression of the actor – almost as good as the real thing. It is Moore’s children – particularly his fabulously louche-looking son Geoffrey – who provide most of the insights in this trip through the family archives.

It starts with his early work modelling knitwear and runs through to playing James Bond and pool parties with Joan Collins and David Niven. Moore was never a great actor, but he was almost impossibly good looking and absurdly charming. He became famous through a mix of good fortune and judicious social climbing. In a neat reversal of his later role as Bond, where he cavorted on screen with an ever younger series of female co-stars, Moore’s first two marriages were to older women. His second wife – Welsh singer Dorothy Squires – was 12 years his senior and instrumental in developing his career. She instigated a move to Hollywood and promoted him tirelessly.

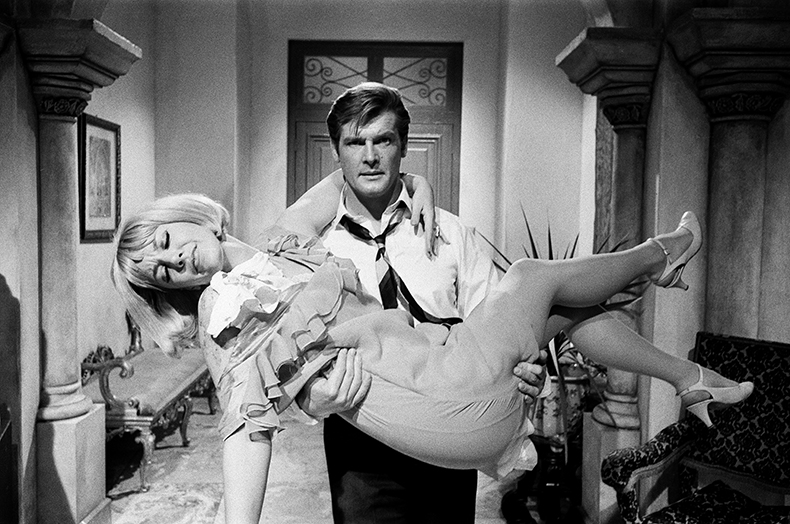

Roger Moore as Leslie Charteris’s debonair hero, Simon Templar, in The Saint, with Aimi MacDonald, in 1968. Photo: Kent Gavin/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Moore graduated from a series of successful TV series including Ivanhoe – adapted from the novel by Sir Walter Scott – to playing Leslie Charteris’s suave, international sleuth, Simon Templar, in The Saint. It was the perfect set-up for Bond, helping him perfect his smooth on-screen persona. Moore’s epic seven Bond-movie run saw a switch in the character from Connery’s super-cool spy with a hint of inner thug to Roger’s foppish parody of a secret agent. Moore had little physical presence beyond his good looks, so he played Bond for laughs, dispatching villains with increasingly strained quips as the films went on. His tenure also coincided with one of the camper periods of men’s fashions, so he appeared decked out in vast flairs, jaunty cravats and powder-blue safari suits.

His first Bond film was Live and Let Die (1973), a critically-panned effort mostly distinguished by an attempt to hitch a ride on the back of the success of the ‘blaxploitation’ films of the early Seventies. It was Moore’s third film, The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), that catapulted the actor and the franchise to superstardom. The film was huge in every sense, a wide-screen blockbuster that nailed the Bond formula: an opening scene – largely unconnected to the main plot – in which Bond has sex before evading almost certain death via an unlikely but highly cinematic escape strategy. After the Maurice Binder-directed title sequence, in which silhouetted naked women perform an erotic gymnastic routine, Bond visits his boss M to receive his ‘mission’. From here he is dispatched around the globe where villainous henchmen lie in wait for him to instigate ever more elaborate chase sequences involving gondolas, powerboats, tanks, rickshaws and – memorably – a Citroën 2CV. It all ends with the destruction of the villain’s Ken Adam-designed evil lair followed by an appalling double entendre as Moore makes out with the one Bond girl still alive.

Moore’s Bond can be seen as either dragging the character into a slow death of bad Dad jokes or reaching new heights of camp brilliance, depending on your point of view. Eventually even Moore realised he was too old to play the role, his thinning hair and leathery skin giving him the appearance of a lecherous uncle at a wedding. No amount of winks to camera could alleviate the sense that Roger Moore was now playing a character called Roger Moore who was under the sad delusion that he was a spy.

From here, the documentary has little more to offer. Moore had a reasonably classy final act as a UNICEF ambassador where his ironic aversion to guns and bombs gave him a new sense of moral purpose. He seems to have been a gentle, good-natured soul, a man who if not exactly overly troubled by moral considerations, appeared to have been consistently generous and kind.

Seemingly, he had few demons or vices beyond cigars and multiple marriages. Fame changed him, but largely on his own terms. One detail reveals the artifice involved in being Roger Moore. Despite filming numerous Alpine chase sequences, Moore didn’t learn to ski until he was in his late fifties. In The Spy Who Loved Me, he performed an audacious ski chase – dispatching scores of evil henchmen, mostly while skiing backwards – several years before he ever set foot on an actual snow slope. It didn’t matter. Being believable in a role was never a problem for Roger Moore, because he always played himself. And, despite his limitations as an actor, he was always brilliant at that.