In one of the first rooms of ‘The Rossettis’, Tate Britain’s current blockbuster, there is a small photogravure reproduction of a sketch by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Elizabeth Siddal with Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1853) shows the artist sitting for a portrait by Elizabeth Siddal. He lounges with his legs up, while she leans forward in observational extremis. Documenting a moment near the beginning of both artists’ careers, this picture hints at the thematic strands threaded through this show: what Jan Marsh calls in the catalogue ‘the longstanding myth of Elizabeth Siddal’ as a timid victim, but also the self-consciousness with which the artists on display pursued their aims, as well as the forms of personal and aesthetic interconnectivity that shaped their work.

The exhibition focuses on Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Elizabeth Rossetti née Siddal, and Christina Rossetti – referred to as Gabriel, Elizabeth, and Christina in the exhibition and this review due to the personal entanglements just mentioned – but touches on work by numerous others. Throughout, the curators – Carol Jacobi and James Finch – seek to show that the paintings, poems, magazines, sketches and even home furnishings of the Rossettis (all of which are abundantly in evidence) are best viewed as the products of reciprocal influence. Gallery-goers, that is to say, should view the Rossettis viewing each other.

One advantage that the curators have in pursuing this aim is the sheer scale and comprehensiveness of the exhibition. Those wishing to see a lock of Elizabeth’s hair, a stunning reproduction of Gabriel-designed wallpaper, a full run of The Germ, manuscript poems, Christina’s original illustrations to her children’s books, photographs of Jane Morris and much more besides will be able to do so. While the Tate has one of the finest collections of work by the Rossettis, this is the first time the gallery has devoted a show to them. The curators have done extraordinary work bringing its holdings together with material from other collections – notably from the Delaware Art Museum.

The Lady of Shalott (1853), Elizabeth Siddal. Photo: © Maas Gallery

Such scale means that exhibition visitors can pursue ideas such as those presented by Elizabeth Siddal with Dante Gabriel Rossetti as they recur. Elizabeth’s The Lady of Shalott from the same year returns to the artist at work, but replaces Gabriel with a mirrored image of Lancelot shown as he distracts Elaine from her weaving. The mirrored gaze returns in a gorgeous gilt panel painted by Gabriel as a wedding gift for William and Jane Morris in 1860; Elizabeth as Dante’s Beatrice and Gabriel as Christ meet each other’s eyes from opposite corners of the frame.

At times, the pursuit of such lines of connection enables visitors to view well-known works in new ways. It adds pathos, for instance, to Gabriel’s The Blessed Damozel (1875–79), painted 15 years after Elizabeth’s death. Here, Gabriel renders the visual axis vertically, showing the Damozel as she leans down from Heaven to observe her earthly lover reclining beneath.

Lady Affixing Pennant to a Knight’s Spear (1856), Elizabeth Siddal. Photo: © Tate

In Gabriel’s wedding present to the Morrises, he depicts himself as the sun and Elizabeth as the moon. But at its best this exhibition invites reflection about who orbits whom. Comparing works such as Gabriel’s The Tune of the Seven Towers (1857) with Elizabeth’s Lady Affixing Pennant to a Knight’s Spear (1856), in which colour and visual arrangement strikingly repeat, shows that, as William Michael Rossetti observed, the ‘detail of invention’ was at times Elizabeth’s rather than Gabriel’s as is often assumed. This exhibition includes the largest number of Elizabeth’s watercolours and drawings to be shown together in 30 years. As such, it offers the best opportunity most viewers will have to make such comparisons for themselves.

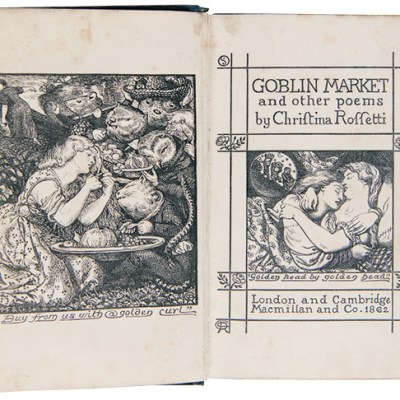

The frontispiece of Christina Rosetti’s Goblin Market (1865). Photo: © Tate

This aim of the exhibition also represents perhaps its greatest difficulty, however, since it makes apparent the kinds of class and gender privilege that shape artistic legacies. Elizabeth’s works are fascinating and weird: Lady Clare (1854–57), for instance, exemplifies an idiosyncratic and distinctive approach to composition and form. But they are also often small, often incomplete and often lost – represented here only in photographic reproductions. Meanwhile, Christina was not primarily a visual artist and so does not have the same presence in the exhibition as the other two Rossettis: the many suggestive wall graphics from her poems can only do so much.

The Blessed Damozel (1875–79), Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Photo: © National Museums Liverpool

For these reasons, the curators have not been able to help making the climax of the exhibition the display of Gabriel’s famous late ‘stunner’ portraits. Nor, more broadly, have they been able to avoid organising the show around the narrative of his artistic development as he graduates from style to style and from female model to female model. The unity, the scale and, yes, the glamour of his work – product and beneficiary of the kinds of privilege this exhibition calls out – mean that it is finally a challenge for the curators to revise the Rossettis’ legacy. The curators show that Gabriel himself often dreamt of arrangements of influence and prestige that challenged accepted norms: ‘We two will live at once, one life,’ he writes in his poem The Blessed Damozel (1850). If, however, this can be read as a vision of collectivity, it is also a paean to the exceptional, consuming self.

Lady Clare (1854), Elizabeth Siddal. Private collection

‘The Rossettis’ is at Tate Britain, London, until 24 September.