For Byzantinists looking up into the dome of the Rotunda in Thessaloniki, 29 metres and more above the pavement of the church of St George, the sense of loss of some of the angels and all but a small portion of Christ’s nimbus, the central figure they supported, is as keen as the loss of many of the figures from the pediments of the Parthenon is to classicists. What remains are, to paraphrase The Waste Land, the fragments that we have shored against our ruins. Of these fragments – and I include the Summer Palace in Beijing and Masaccio’s frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel – the Rotunda is surely among the most impressive. Up to the base of the dome a cylinder, more than 24 metres in diameter with walls more than six inches thick, is flooded with light from eight large arched windows; an arrangement that leaves the mosaics above in relative obscurity yet, at the same time, a vision of a fantastic architecture peopled with 16 saints, their arms extended in prayer. Most of those mosaics have vanished but there survives a central medallion, ringed with paradisal vegetation and stars, that contained what was probably a standing Christ.

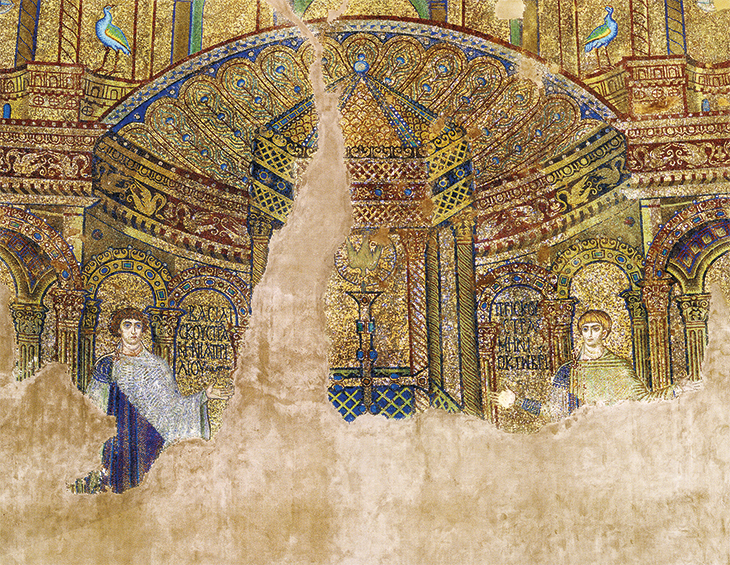

Panel showing the soldier martyrs Basiliskos and Priskos in the Rotunda (Church of St George), Thessaloniki, built between 305-11; mosaics from the 5th or 6th century. Photo: Bente Kiilerich

Sixty years ago, younger and sprightlier students, like the creator of these two volumes (and the author of this review), could climb the scaffolding and survey at close hand what by then had been shored up. Since then much has happened: on the one hand the earthquake of 1978; on the other, the boom in the last decade of scholarship on mosaics. These banner years began in 2007 with the publication of Ann Terry and Henry Maguire’s two-volume Dynamic Splendor: The Wall Mosaics in the Cathedral of Eufrasius at Poreč, followed in 2012 by Charalambos Bakirtzis and Eftychia Kourkoutidou-Nikolaidou’s long chapter in their Mosaics of Thessaloniki: 4th–14th Century.

Terry and Maguire’s superbly illustrated volumes are now followed by the book at hand. Neither is available online, a lacuna that further marks how expectations have changed since 2007. The transformation is no less evident in the language we use (sometimes to the dismay of the present writer). In the second half of the 20th century we could stand on the platforms of the scaffold, inspect the nature of the mosaicists’ achievements, and feel as if we were present at the creation. Nowadays, of course, a platform is an electronic thing, a digital framework that supports a scholar’s images and observations. It can carry and, when invoked, transmit an unlimited body of visual evidence sufficient to accommodate many of the hundreds of colour photographs made in 2009 and 2015 by Bente Kiilerich, the invaluable partner of Torp’s researches and a major scholar in her own right. Beyond her contribution on the portraits of the martyrs in the book, she has elsewhere written important articles on ivory, stone carving, and silver vessels of around 400, papers with which I am not always in agreement, but which contribute to the vexed question of the date of the Rotunda’s mosaics.

Detail showing the face of the martyr Onesiphoros in the Rotunda, Thessaloniki. Photo: Bente Kiilerich

The images, laid out together with older documentary photos, are clear improvements upon those previously published. For example, the sections of the dome with the underdrawing of Christ is the best reproduction of this nodal, if vestigial, presence. Below, the compartment containing the ‘thème dogmatique’, flanked by Basiliskos and Priskos beneath the remarkable swan frieze, reads more brightly than the dingy image in Myrto Hatzaki’s essay in The Mosaics of Thessaloniki Revisited (2017; ed. Antony Eastmond and Hatzaki), a collection deriving from a symposium at the Courtauld Institute in 2014. Even more striking are the martyrs in close-up: the face of Onesiphoros offers not only asymmetrical cyan irises in the eyes but such telling details as the zone to the left of his mouth where white, grey and possibly gold tesserae have dropped out. Is it too cynical to recall the words of Liz James, who writes in Mosaics in the Medieval World (2017) that ‘[t]o an extent, to the mosaicists, installing a mosaic was just another job’, before adding: ‘In the Rotunda […] the workmanship and detail of the mosaicists is ridiculously good’. This down-to-earth approach might seem to run counter to Torp’s description of the craftsmen’s task – ‘à visualiser la Maison de la Lumière Véritable par des matériaux du monde d’ici-bas’ – the art-historical equivalent of the difference between British pragmatism and ‘Continental’ philosophy. But in the 400 pages before this proclamation, Torp sets out in detail the architectural setting in which the mosaicists worked and the means by which they operated, not to speak of his arguments for its spiritus rector, which converge on Theodosios I (r. 379–395). He is, however, less concerned with their cultural context, ignoring the detailed discussion in Robin Cormack’s Byzantine Art (2000), not cited in his bibliography. Instead of such generalities, we are provided with telling details like the pudgy-faced angel whose right hand struggles to negotiate the space beneath its overlying wing, an image that shows that perfection was not visited on all these heavenly creatures and that they are not all as lissom or handsome as one remembers them from a first encounter.

Detail of angel supporting the medallion at the apex of the dome in the Rotunda, Thessaloniki. Photo: Bente Kiilerich

James’s monograph and the Courtauld papers presumably arrived too late for Torp to consider them in La Rotonde Palatine. This is especially to be regretted for he does not appear to answer the challenges about the monument’s building history thrown down by Beat Brenk in the latter volume, nor does he return to the problem surrounding the radiocarbon dating (late 4th to early 5th century) of mortar taken from an unidentified area of the building that he himself raised in the same collection. One cannot discern these absences from the index which, in a volume that will surely become the standard work on the building, is entirely insufficient. (By contrast, the primary sources he employs are easily discovered via a combination of the ample notes that follow each chapter, the bibliography of ‘auteurs et textes anciens’, and the index of proper names). Excluded, for example, are references to the use of silver in the tesserae, an important datum frequently reported in the book. Neither the exhaustively analysed elements of the ‘Palais-Temple céleste’ nor the precious, detailed record of the dress displayed by the honour guard of saints before it can be accessed through the index. This, then, is not a reference tool, but an immense and comprehensive undertaking – a major stage, but certainly not the last word in more than a decade of active debate – that is essential reading for anyone actively engaged with the architecture, mural decoration and political theology of Late Antiquity.

La Rotonde Palatine à Thessalonique: Architecture et Mosaïques (2 vols.) by Hjalmar Torp is published by Éditions Kapon.

From the July/August 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)