When he folded and draped canvases in the late 1960s, Sam Gilliam challenged the traditional premises of painting. Five decades on, he tells Apollo, his need to make art is as urgent as ever.

The exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel is titled ‘The Music of Color’. How important has music been to your work?

That’s a title which the director of the museum has given the show. It’s actually in honour of Walter Hopps, who was one of the best curators of contemporary art in America. His first statement to me was that he liked me because I liked John Coltrane. I never told him that I liked Thelonious Monk or Dave Brubeck or Miles Davis too; I grew up listening to jazz and certain classical music – Tchaikovsky and particularly Ravel.

Crystal (1973), Sam Gilliam. Photo: Fredrik Nilson/Courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles; © 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich

Do you feel that your work shares things with music?

Art and music are about structure: the way you put things together, and

the end point. The way that you arrive at concepts through practice, through experimentation. Things are situational; I determine what I’m going to do next by the path I’ve already taken or what I already think about.

The exhibition focuses on your work from 1967–73. Do you look at those pieces in a different way with five decades of hindsight?

I certainly do. For me, the period that the museum is concentrating on is simply a palette to think about the whole of the time between the late ’60s and what I’m doing now. When you’re old you start thinking about structural concepts all over again.

You took some radical decisions at the time – taking the canvas off the stretcher, folding it, and draping it, too. What motivated those choices?

I’d learned that there is no difference between painting and sculpture, or sculpture and architecture. Or at least, there are ways that the three-dimensional aspect of space is defined by the flatness of the plane. I thought a lot about these things through teaching, and wanting to be as defining as the people whose art I liked. Living in Washington, I was interested in Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis, and the younger artists here that were following them – one of the painters, Thomas Downing, was a very good friend. And I ended up going to shows in Europe quite early. I looked at the whole of other artists’ careers to see what they arrived at in the end, and made that a starting point, a point for experimenting, to see if I could go further. You have to go outside the frame in order to make work.

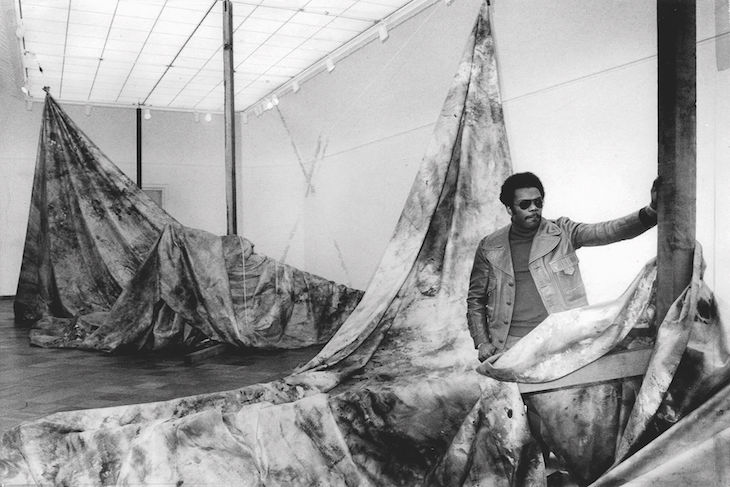

Sam Gilliam with Autumn Surf, installation view of ‘Works in spaces’ at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1973. Photo: Art Frisch/Courtesy San Francisco Chronicle; © 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich

I realised that a couple of things were happening in my work. Colour is one of

the most fundamental; it’s a fundamental part of painting, but also one of the most adventurous aspects. Taking the canvas off the stretcher to make it free was another adventure. It happens in Asian art, in the art of India, or in something as simple as tie-dyeing. The folding created structure, movement through the work. I still do the same thing that Velázquez or Rubens or Rembrandt would have done. I think the end point is the same, but I just moved the needle. The old is refreshed by the new, the new refreshed by the old.

It must be satisfying to have seen your work celebrated in a number of exhibitions in recent years. What has it taken to reach this point?

I’ve always insisted on remaining an artist. When there’s been a struggle, I’ve insisted on the struggle, and on the content that I wanted. By teaching – I’ve taught a lot – I never forgot the lessons that I learned while I was a student about the importance of process, the process of actually thinking carefully about the things you ought to do.

I’ve always been a part of a workshop, and I’ve never stopped thinking about what I consider prominent paintings – in the National Gallery in Washington, or in New York or Europe. I’ve also been very much stimulated by my race, and the process that’s come through Mandela or Martin Luther King, as well as the concept of what democracy is now, the peace movement, and things like that. I think that there’s a way of looking at things as a whole that defines what we should do. When you take things as a whole, like an orange, then you can remove the peel and get the fruit.

Ruby Light (1972), Sam Gilliam. Photo: Cathy Carver/Courtesy the artist and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; © 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich

Do you still find painting exciting?

Yes, but I’m more excited by sculpture, and doing large-scale things with the drapes. I still do a lot of teaching, too, because we’re still thinking about how to build art galleries, art museums, and art careers for young people. What we ask now of America is the same freedom upon which it was founded, and not the depredation that’s coming about through Trump and the Republican Party. We ask for a future for the young and for continuity of the earth, for maintaining it as a clean space. Art is a type of criticism now – of Trumpism, of the rewriting of fascism, of what is evil. It makes me glad to be an artist.

‘The Music of Color: Sam Gilliam, 1967–1973’ is at the Kunstmuseum Basel until 30 September.

From the June issue of Apollo. preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)