Though among the first soft fruits of the British summer season, the cherry was once associated with Christmastide. It featured in apocryphal stories of the Virgin Mary at the Nativity and was laden with notions of good fortune and celestial wealth – as a perusal of medieval embroidery, pilgrim badges, manuscript illuminations, and mystery plays reveals.

In modern popular culture, however, the cherry is a symbol of sex. We all know the phrases, like ‘popping your cherry’, and visual images of the cherry often have sexual connotations. There is a scene in the music video for the song ‘Blow’ by Beyoncé with others, which features the singer on all fours, writhing rhythmically atop a sports car. Behind her, in pink neon lights, is the word ‘Cherry’. In the lyrics to ‘Blow’, the cherry is a stand-in for sex, alongside sweets, especially Skittles: small, numerous and unequivocally erotic. And, perhaps you have seen the symbol of the night club, Pacha, in Ibiza, which is two ripe, Pop-art cherries? The marketing message isn’t subtle. Which prompts the question as to whether there is anything left of the medieval meaning in our own time.

Pilgrim badge, mid 15th century, English. British Museum, London. Photo: © Trustees of the British Museum

A useful – and surprising – clue to the change in the symbolic meaning of cherries may be found in the once silver-bright form of a 600-year old badge. The majority of medieval badges were designed to invoke the protection of a saint and often represent a holy figure, usually made identifiable by an emblem derived from saints’ lives. Sometimes an emblem alone is depicted (St Thomas Becket’s gloves) or a whole scene (St Alban’s martyrdom). The badges are generally made from pewter, with pins on the reverse to allow them to be fixed to clothing, and most date from the 14th and 15th centuries. They are often delightfully baffling: their iconography unclear, their erstwhile owners mysterious.

Until recently, five surviving badges in particular fell into this category. They show a medieval hood, with seven small, long-stemmed fruits where one would expect to see a human face. Although excavated from the banks of the Thames in the mid 19th century, it is only now that they are being properly interpreted; for one thing, the badges were being viewed upside down. Turned the other way up, the iconography relinquishes some of its mystery; it is clear that the hood’s ribbon is tied tightly around the neck of the collar and the hood is being used as a sack to hold fruit. This is a distinctive image. Would an object designed to be emblematic be the only instance of this kind of imagery? It seems unlikely.

An ‘unofficial’ harvest of cherries, in which a hood is used as a makeshift bag, is depicted on folio 196v of the early 14th-century Luttrell Psalter. In this case, a young thief is shown scrumping (stealing fruit) from a cherry tree. He is depicted up the tree with his hood back-to-front. Both the hood and his cheeks are crammed with fruit and another figure, perhaps the owner of the tree, gesticulates angrily from the ground. The psalm text above the image reads, ‘They were troubled and moved like a drunkard, and all their wisdom was consumed.’ The cherries, in this instance, may represent the wisdom ‘consumed’ before the ‘troubled’ ones described by the Psalmist. The illuminator has taken care to represent the cherry tree’s leaves, bark and the colours of the ripening fruit accurately. The miniature appears as part of a sequence of images of country life, so scrumping fruit in this way may have been a common rural sight. On the badges, as in the Psalter, the hood’s use for this purpose signals the impromptu nature of the harvest.

An ‘unofficial’ harvest of cherries, in which a hood is used as a makeshift bag, is depicted on folio 196v of the early 14th-century Luttrell Psalter. In this case, a young thief is shown scrumping (stealing fruit) from a cherry tree. He is depicted up the tree with his hood back-to-front. Both the hood and his cheeks are crammed with fruit and another figure, perhaps the owner of the tree, gesticulates angrily from the ground. The psalm text above the image reads, ‘They were troubled and moved like a drunkard, and all their wisdom was consumed.’ The cherries, in this instance, may represent the wisdom ‘consumed’ before the ‘troubled’ ones described by the Psalmist. The illuminator has taken care to represent the cherry tree’s leaves, bark and the colours of the ripening fruit accurately. The miniature appears as part of a sequence of images of country life, so scrumping fruit in this way may have been a common rural sight. On the badges, as in the Psalter, the hood’s use for this purpose signals the impromptu nature of the harvest.

The Luttrell Psalter miniature may also help in the identification of the fruits shown on the badges. In solely formal terms, the roundness of the fruits and long stems make it likely that they were intended to be read as either apples or cherries. If they are meant to be the latter, then they are oversized, but then again, so are the cherries in the hood of the thief. This inconsistency in scale is a stylistic choice that suits miniature rendering. Given their cherry-like form and given that the earlier English illustration unequivocally represents cherries, it seems likely that the badges depict this fruit. This is not immediately obvious from the formal evidence alone, and may not have been so even to a medieval viewer. However an unexpected cherry-harvest played a central part in a story that enjoyed a short burst in popularity during the mid 15th century, that is, during the period to which these badges can be dated, based on the style of the hood.

In the mid 15th century mystery-play cycle, known as the N-Town Plays, there is an episode devoted to the Nativity. In it, Joseph and the Virgin are travelling to Bethlehem in the middle of winter and en route Mary observes a cherry tree which unseasonably ‘blomyght now so swetly’ (blooms now so sweetly). She asks her husband to pick her some of the cherries, to which Joseph churlishly replies, ‘lete hym pluk ȝow cheryes begat ȝow with childe’ (let he who got you with child pluck the cherries). At this, the tree miraculously bows down to offer its fruits to Mary.

The scene is still performed in modern Christmas services in the lyrics of the ‘Cherry Tree Carol’. A version of the song was collected by Francis James Child in the 19th century. In the final stanzas, the Christ Child compares the descending cherries to the stars of heaven:

And the cherry trees bowed down, bowed low to the ground,

And Mary gathered cherries while Joseph stood round.

Then Joseph he kneeled down and a question gave he,

“Come tell me, pretty baby, when your birthday shall be.”

“On the fifth day of January my birthday shall be,

And the stars in the heaven shall all bow down to me.”

The origins of the tale can be found in the Apocryphal Infancy Gospels, and specifically the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, a widely read, quasi-biblical source. In the latter, however, the tree is a date palm not a cherry, and it descends at the request of the unborn Christ Child. The date palm’s transformation into a cherry tree appears to be a purely English reinterpretation of the tale. When and why this took place is unclear. One explanation could be that the plays were performed outdoors and the change permitted summer actors to use an actual branch from a cherry tree as a prop. Alternatively, it may simply be that dates were unfamiliar to an English audience and the better-known native cherry was full of symbolic potential. Another possibility arises from the evidence of an English embroidery fragment dated 1390–1420, which shows a fruiting branch bending to the Virgin and the infant Christ Child. As is to be expected given the artists’ locale, the branch looks nothing like a date palm. It would be easy for viewers to mistake such visualisations (and more like it probably existed) for images of a cherry tree, even resulting in a process of Chinese whispers between text and images. In any case, it shows that the story of Mary and the miraculous fruit was present and ambiguous in deluxe English art prior to the composition of the N-Town Plays.

Scene from the life of the Virgin and Child, showing a fruit tree bending overhead (one of six fragments), (1390–1420), English. Victoria and Albert Musuem, London

The motif associating cherries with the Virgin and Child also appears in The Shepherd’s Play of the Wakefield Master, who was active in the mid to late 15th century. Here the shepherds visit Mary and Christ in the stable, bringing gifts that reflect their status as poor men. The first shepherd, a lowly version of the first Magus, gives Mary and the infant Christ not gold, but ‘a bob of cherys’ (a bunch of cherries), saying that he has ‘holden my hetyng’ (kept my promise). Crucially for understanding the badge, as well as the wider cultural importance of the cherry, it is a humble substitute for actual treasure.

Cherries as marvellous, unseasonable fruit, and the themes of wealth and devotion to the Virgin and Child also appear in the Middle English romance Sir Cleges. The eponymous knight, who has a young wife and children, prays beneath a wintry tree to be delivered from poverty. He looks up to see the tree miraculously covered in cherries. At first he sees the miracle as an ill omen, but his wife insists ‘It is tokenyng / Off mour godness, that is comyng’ (a sign of more goodness to come). He and his son dress in the clothes of shepherds and take the cherries to the king, who, in thanks for this mid-winter gift, raises the knight and his family out of poverty. In one of the manuscripts that preserve the text, the poet informs the reader that the knight held a Christmas feast in honour of the Virgin and Christ every year for 10 years thereafter. Scholars have argued that Sir Cleges draws from the tale of Mary and the cherries in the N-Town Plays, although in this case the miraculous cherries translate into material riches.

The literary historian Sherwyn T. Carr has noted the rise of this literary motif in medieval English texts of the 15th century but suggests that it never became a ‘true icon’. But if an icon is a representative symbol with a consistent meaning over time, then we think the cherry did have some stability. That meaning, we suggest, is an idea of spiritual riches or the hope of riches to come, frequently associated with virginity and the Virgin.

The above examples all reflect a vernacular, even dramatic, motif that circulated, like pewter badges, in the general populace. The memorable image of the miraculous cherry tree is further bolstered by the widespread association between Mary, the Nativity of Christ and fruit in the prayer known to every Christian of medieval England – in the words ‘blessid be the fruyt of thi womb’ that appear in the Middle English Hail Mary, spoken repeatedly while praying the Rosary. Likewise, the Middle English word for cherry (chery), is nearly homophonic with the Middle English words for ‘dear’ or ‘precious’ (cher) and ‘happiness’ (cheer). And perhaps it is not too much to wonder whether these practices in Marian devotion have roots in that of Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture, maternity and fertility. In any case, Sir Cleges’s wife might interpret badges like the hood-of-cherries badges as tokens of ‘goodness to come’. Were they worn as good-luck charms, betokening a sudden harvest, whether of happiness, wealth, love, fertility or all of the above? Was it, perhaps, a souvenir associated with a shrine to the Virgin?

The link between various configurations of the Virgin, female virginity, cherries, and good fortune held wider currency in medieval Europe. A reference to a rosary made of carved cherry stones can be found in the 14th-century Old French poem Pamphile et Galatée: ‘En sa main unes patrenostres / De noiaus traués de cherises / Dont elle fait ses sacrefices (in her hand she has a rosary made from carved cherry pits, with which she says her prayers).

Madonna and Child, (c. 1525–30), Quinten Massys (and/or studio). Mauritshuis, The Hague

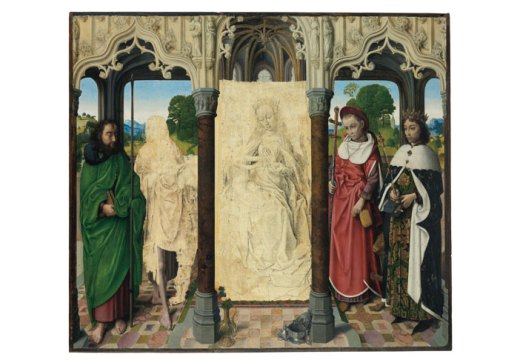

The Virgin-cherry association persists in Renaissance art, appearing in works by Flemish and Italian artists such as Joos van Cleve, Quinten Massys, Bartolomeo Montagna, Titian, and Leonardo da Vinci. In a tender depiction of the Virgin and Child by Massys (c. 1520s), the meeting of the Virgin’s lips with those of the Christ Child strikes a visual consonance with the pair of cherries held in her right hand. The viewer may also be expected to detect, in the red tone of the fruit, the blood of the Crucifixion. Whether, in these cases, it is related to the English modification of the legend of the date palm, or a manifestation of a more general association between the Virgin and fruit, is uncertain. The motif is nevertheless pervasive and, given that the fruits are often depicted in pairs, is a visual allusion to maternal lips and nipples. In Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in the mechanicals’ play, Thisbe professes to a wall, ‘my cherry lips have often kissed thy stones.’ The potential for two readings – one innocent, one worldly – is a pattern for the post-medieval meaning of the cherry.

Later, cherries appear in secular art as a motif accompanying portraits of children. One of these is of the toddler, Lady Mary Beauclerk (1793–94), painted by James Earl. The red cherries create an arresting contrast with the sitter’s white dress and call to be read as evocations of purity and youth. Nearly a century later, Cherry Girl by Joseph Caraud is not unique in its subject, but takes a rather different approach to the fruit. The painting shows a young woman, in a provocatively ruched dress, encircling a bowl of cherries with her left hand and drawing it towards her white apron. Her right hand takes cherries from the bowl and she fixes the viewer with a supercilious, confident gaze. The threat of staining the apron at the level of her pelvis is suggestive enough, without taking into account her low-cut bodice and the cross-shaped pendant hanging teasingly beneath the curve of her chest. The painting reads like a fantasy of the ‘good’ girl with ‘bad’ ideas.

Moving away from fine art and into the world of informational posters, a mid 20th-century advert for tinned fruit and vegetables, produced for the Ministry of Agriculture, suggests that tinned cherries are just as tempting as those from the tree. A fresh-faced boy in school uniform scrumps from the bowl, in a serendipitous reincarnation of the Luttrell Psalter thief. His eyes dart sideways, in anticipation of being caught ‘red-handed’. As in the artistic trail, there is the same ambiguity here in the cherry as a symbol of purity and of desire.

Lady Mary Beauclerk, Daughter of Lord Aubrey and Lady Jane Beauclerk (1793–94), James Earl. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville

Cherry Girl (1875), Joseph Caraud. Private collection

Is this ambivalence the thread that connects the medieval association with the modern? The first modern instance of the cherry as a term for the hymen is recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary and dates from 1889. The accompanying quotation there is somewhat uninformative, but suggests an association between cherries and youth. The next quotations from the 1920s and 1930s suggest that in prison slang cherry had come to mean virginity or virgin. The origin of this link is still hazy, however. One possible explanation comes from a proverbial expression, to take two bites of a cherry, meaning ‘to take or have a further opportunity to achieve something’ and also, a second bite at the cherry, meaning, ‘a second chance’. The saying hinges on the belief that cherries are, in the end, a one-bite morsel.

Virginity is also meant to be gone after a single ‘bite’. Perhaps this explains why it felt natural to the medieval mind to associate an unseasonal crop of mid-winter cherries with a figure whose virginity remained intact after conception; is Mary a figure of impossible abundance? The change in meaning may also highlight an aspect of the modern West’s prudishness when it comes to sexual female bodies. The cherry of virginity now is risqué, but less so in the Middle Ages when it could serve as a symbol of maternity as well as of sexual ripeness. But from a Yuletide miracle to Beyoncé, medieval badges to modern posters; cherries are – excuse us – ‘popping’ with significance. Spare a thought for their rich history if they are served this Christmas: glacé, soaked in booze, or shipped fresh from lands unknown to the medieval West.

From the December 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze