‘This Booke, / When Brasse and Marble fade, shall make thee looke / Fresh to all Ages’: so announces a prefatory poem in Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, today known as the ‘First Folio’. Printed in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death, the Folio resulted from the joint efforts of his fellow actors and friends, John Heminge and Henry Condell, to create a collected edition of his plays. A copy, currently owned by Mills College in Oakland, California, will be auctioned by Christie’s in New York on 24 April this year. Beforehand, though, the book is undertaking a global tour with appearances in London, New York, Hong Kong and Beijing, an itinerary that reflects the recent surge of interest in Shakespeare in China – the author was once banned by Mao Zedong. Although almost 240 partial or complete copies exist – with 82 of these at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. – a Folio only rarely goes on sale and there are currently estimated to be just six complete copies in private hands. The last time one was auctioned, in 2001, it sold for $6,166,000.

I visited Christie’s in London to see the Folio during its time in the capital. Upon encountering the book, what immediately stands out is its hefty, monumental quality: printed in the prestigious folio format (two leaves per sheet), it visually elevates Shakespeare’s plays to the status of literary ‘works’. For the book’s publishers in 1623, this was a daring move. Plays in this period were still considered somewhat lowbrow entertainment: only a decade earlier, Thomas Bodley had excluded printed plays from his library in Oxford on the grounds that they were ‘riffraff’. This particular copy of the Folio is both complete and pristine, a fact that reflects its careful preservation over the last four centuries. In the early 19th century, the book’s then owner consulted Edmund Malone, the great Shakespeare scholar, to verify its authenticity and completeness. Malone gave the copy his imprimatur, and recommended the light restoration work that we see on the frontispiece today. However, the book’s remarkably clean condition also suggests a tension between its status as a luxury commodity and a collection of plays. After all, who could enjoy reading Twelfth Night in a copy worth $6 million?

Courtesy Christie’s

Opening the Folio to the first page, we encounter Martin Droeshout’s familiar engraving of the playwright. A balding man in a ruff and doublet, the image in fact reveals little about Shakespeare himself, whose life remains teasingly enigmatic despite centuries of scholarly research. Perhaps this is the point, though. Even as it foregrounds Shakespeare’s face and name, the Folio presents us with a somewhat elusive and otherworldly figure, downplaying the role of collaborative authorship and of Shakespeare’s theatrical company, the King’s Men, in the production of these plays. In their prefatory letter to the readers, Heminge and Condell portray Shakespeare as a solitary genius, reporting that ‘what he thought, he uttered with that easiness, that we have scarce received from him a blot in his papers’. Attributing to Shakespeare such preternatural fluency, the Folio set the stage for a long history of bardolatry, seen nowhere more clearly than in past and present collectors’ enthusiastic pursuit of the book itself. Part holy relic, part sacred text, the Folio formed the basis for a secular cult of Shakespeare in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Even leaving aside the more fanatical elements of the book’s reception, it is difficult to overestimate the Folio’s impact on Western literary and cultural history. Of the 36 plays included, 18 had never been printed previously; the Folio thus preserved plays such as Macbeth, Julius Caesar and The Tempest for posterity. Its division of the plays into comedies, histories and tragedies also cast a long shadow over our understanding of Shakespeare, as did the absence of the sonnets and narrative poems from the collection. For a long time, the omission of the poems was taken to indicate their lesser importance in Shakespeare’s oeuvre. Today, scholars tend to assume that it was the popularity of the poems, and thus the cost of acquiring copyright, that prevented their inclusion.

While the commercial value of the Folio may be one measure of Shakespeare’s continuing significance, then, another is the frequency with which his plays are being watched and read. Shakespeare enthusiasts need not fear: the Royal Shakespeare Company is currently producing Chinese translations of the Folio plays, in a collaboration between translators and theatre practitioners that aims to bring Shakespeare alive for new audiences. The collection is due to appear in 2023, in time to celebrate the 400th anniversary of this exceptionally vital book.

Tessa Peres is writing a PhD on Shakespeare at the University of Cambridge.

Shakespeare’s First Folio will set you back millions – but its cultural value is immeasurable

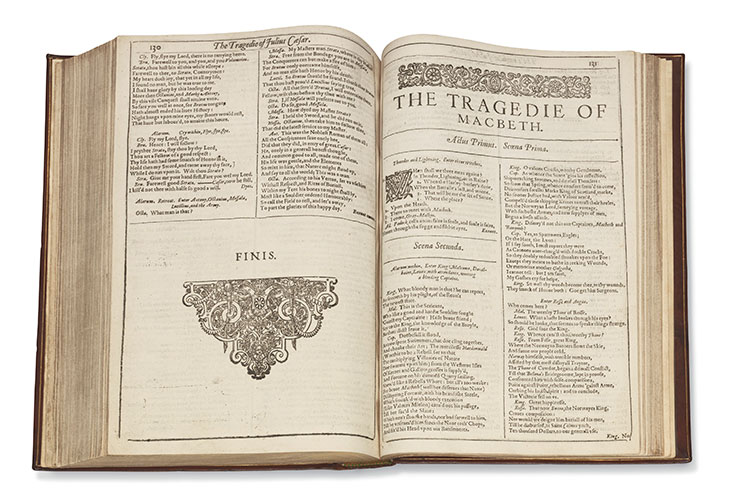

A copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio, coming to auction at Christie’s, New York, on 24 April Courtesy Christie’s

Share

‘This Booke, / When Brasse and Marble fade, shall make thee looke / Fresh to all Ages’: so announces a prefatory poem in Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, today known as the ‘First Folio’. Printed in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death, the Folio resulted from the joint efforts of his fellow actors and friends, John Heminge and Henry Condell, to create a collected edition of his plays. A copy, currently owned by Mills College in Oakland, California, will be auctioned by Christie’s in New York on 24 April this year. Beforehand, though, the book is undertaking a global tour with appearances in London, New York, Hong Kong and Beijing, an itinerary that reflects the recent surge of interest in Shakespeare in China – the author was once banned by Mao Zedong. Although almost 240 partial or complete copies exist – with 82 of these at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. – a Folio only rarely goes on sale and there are currently estimated to be just six complete copies in private hands. The last time one was auctioned, in 2001, it sold for $6,166,000.

I visited Christie’s in London to see the Folio during its time in the capital. Upon encountering the book, what immediately stands out is its hefty, monumental quality: printed in the prestigious folio format (two leaves per sheet), it visually elevates Shakespeare’s plays to the status of literary ‘works’. For the book’s publishers in 1623, this was a daring move. Plays in this period were still considered somewhat lowbrow entertainment: only a decade earlier, Thomas Bodley had excluded printed plays from his library in Oxford on the grounds that they were ‘riffraff’. This particular copy of the Folio is both complete and pristine, a fact that reflects its careful preservation over the last four centuries. In the early 19th century, the book’s then owner consulted Edmund Malone, the great Shakespeare scholar, to verify its authenticity and completeness. Malone gave the copy his imprimatur, and recommended the light restoration work that we see on the frontispiece today. However, the book’s remarkably clean condition also suggests a tension between its status as a luxury commodity and a collection of plays. After all, who could enjoy reading Twelfth Night in a copy worth $6 million?

Courtesy Christie’s

Opening the Folio to the first page, we encounter Martin Droeshout’s familiar engraving of the playwright. A balding man in a ruff and doublet, the image in fact reveals little about Shakespeare himself, whose life remains teasingly enigmatic despite centuries of scholarly research. Perhaps this is the point, though. Even as it foregrounds Shakespeare’s face and name, the Folio presents us with a somewhat elusive and otherworldly figure, downplaying the role of collaborative authorship and of Shakespeare’s theatrical company, the King’s Men, in the production of these plays. In their prefatory letter to the readers, Heminge and Condell portray Shakespeare as a solitary genius, reporting that ‘what he thought, he uttered with that easiness, that we have scarce received from him a blot in his papers’. Attributing to Shakespeare such preternatural fluency, the Folio set the stage for a long history of bardolatry, seen nowhere more clearly than in past and present collectors’ enthusiastic pursuit of the book itself. Part holy relic, part sacred text, the Folio formed the basis for a secular cult of Shakespeare in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Even leaving aside the more fanatical elements of the book’s reception, it is difficult to overestimate the Folio’s impact on Western literary and cultural history. Of the 36 plays included, 18 had never been printed previously; the Folio thus preserved plays such as Macbeth, Julius Caesar and The Tempest for posterity. Its division of the plays into comedies, histories and tragedies also cast a long shadow over our understanding of Shakespeare, as did the absence of the sonnets and narrative poems from the collection. For a long time, the omission of the poems was taken to indicate their lesser importance in Shakespeare’s oeuvre. Today, scholars tend to assume that it was the popularity of the poems, and thus the cost of acquiring copyright, that prevented their inclusion.

While the commercial value of the Folio may be one measure of Shakespeare’s continuing significance, then, another is the frequency with which his plays are being watched and read. Shakespeare enthusiasts need not fear: the Royal Shakespeare Company is currently producing Chinese translations of the Folio plays, in a collaboration between translators and theatre practitioners that aims to bring Shakespeare alive for new audiences. The collection is due to appear in 2023, in time to celebrate the 400th anniversary of this exceptionally vital book.

Tessa Peres is writing a PhD on Shakespeare at the University of Cambridge.

Share

Recommended for you

Venus enlargement? Marlene Dumas takes on Shakespeare’s erotic verse

The artist is one of few to have attempted to illustrate Venus and Adonis

The pyramids at Giza looked very different when they were first built

The Egyptian pyramids were originally covered in smooth white limestone – as a casing stone now in Scotland shows

Artists exhibiting at MoMA PS1 call on museum to drop board members

Art news daily: 15 January