A recent mosaic find in London gives us a new glimpse of the lives of the privileged during Roman Britain. It has emerged during excavations for a new property development, the Liberty of Southwark, where the river crossing at London Bridge touched down on the south side of the river. The scatter of buildings here was outside the city proper; the website for the Liberty of Southwark development makes much of this, linking it enthusiastically to Southwark’s earthy reputation in later ages (‘this was always Londinium’s wild side’). More prosaically, the suburb here lined an important arterial road leading up from the ports on the south coast and would have seen a steady procession of travellers and cargo passing into London, and Britain, from the continent.

Travellers need somewhere to stay, and a large courtyard structure at the site, first dug in the 1980s and now re-explored, might have been a mansio, a Roman ‘hotel’ or waystation for official travellers, dating to around 72 AD. This building stayed in use for some time and was periodically redecorated. One later phase in the late second or early third century produced this very impressive recently uncovered mosaic, the largest found in London for more than 50 years.

Photo: Andy Chopping; © Museum of London Archaeology

The find offers fresh evidence of the ways that artistic influences from abroad have fed into London’s cultural life ever since it was established at an important crossing point on the navigable Thames shortly after the Roman invasion of Britain. Destroyed under Boudicca’s revolt in 60–61, the city later prospered as Rome consolidated its grip on the island and pushed the frontier of empire northwards, eventually to Hadrian’s Wall and beyond. Although London was never in the first rank of Roman cities – it never acquired an aqueduct, for example – it was large and prosperous enough to generate a fine range of public and private buildings.

As a port linking Britain to the continent it was an important entry point for the tastes, fashions, material and personnel which were an important part of Rome’s appeal to parts of the conquered British population. The Roman historian Tacitus memorably described how, as the military governors of the island ‘gave private encouragement and public assistance to the building of temples, forums, and private houses […] an esteem sprang up for our style of dress, and the toga became fashionable. Step by step [the Britons] were led to things which dispose to vice: porticoes, bathing, the elegance of banquets. All this in their ignorance, they called civilisation, when it was in reality a part of their servitude.’

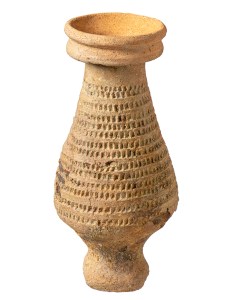

Unguentarium (bottle for scented oils), found during the excavations. Photo: Andy Chopping; © Museum of London Archaeology

Despite Tacitus’ mordant take on the trappings of Roman ‘civilisation’, it seems that Roman material luxury was genuinely popular in its subject provinces. And why not? A colourful mosaic pavement laid over a suspended, heated floor was a practical comfort in a damp and chilly island. Its cheerfully regular patterns suggested a well ordered, cultured, and prosperous household. The rooms it furnished, whether used for private luxury or public display (or both), provided those who could afford it with a distinctive and comfortable way of life.

The Southwark mosaic is conspicuous both for its size and quality. It includes two highly-decorated panels set within a floor comprised of red tesserae. Fragments of brightly painted wall plaster suggest that the room in which the mosaic was located was also highly decorated. Romans used high-status decorations in rooms where they entertained, and mosaics, which can easily be swept or cleaned, are practical in such spaces; this one may well have been a triclinium or dining room.

Decorated wall plaster found during the excavations. Photo: Andy Chopping; © Museum of London Archaeology

The larger panel has colourful stylised flowers set within black and white guilloche borders and chequers, with a red and white guilloche framing the whole. To one side there is a pattern known as Solomon’s knot, a cross shaped formed of two interlinking loops. This larger panel shows similarities to other floors laid by a local team of Londinium mosaicists, the ‘Acanthus Group’, who developed their own variants of these typical elements: a sign of enough demand to fuel a local interior decoration industry, drawing on fashionable Roman designs.

The second, smaller panel tells a slightly different story. This has two more Solomon’s knots, framed by groups of shield-shaped pelta motifs and more flower elements. According to David Neal, formerly of English Heritage, the design of this panel is very similar to mosaic work from Trier, one of the most significant towns in Roman Germany. It suggests the movement of craftsmen between the two provinces, reminding us once more of Londinium’s history of cultural and economic exchange with its European neighbours.

Matthew Nicholls is Senior Tutor of St John’s College, Oxford, and Visiting Professor of Classics at the University of Reading.

The well-to-do Britons who wanted to keep up with the Romans

Roman mosaic (2nd–3rd century), found at Southwark and photographed in February 2022. Photo: Andy Chopping; © Museum of London Archaeology

Share

A recent mosaic find in London gives us a new glimpse of the lives of the privileged during Roman Britain. It has emerged during excavations for a new property development, the Liberty of Southwark, where the river crossing at London Bridge touched down on the south side of the river. The scatter of buildings here was outside the city proper; the website for the Liberty of Southwark development makes much of this, linking it enthusiastically to Southwark’s earthy reputation in later ages (‘this was always Londinium’s wild side’). More prosaically, the suburb here lined an important arterial road leading up from the ports on the south coast and would have seen a steady procession of travellers and cargo passing into London, and Britain, from the continent.

Travellers need somewhere to stay, and a large courtyard structure at the site, first dug in the 1980s and now re-explored, might have been a mansio, a Roman ‘hotel’ or waystation for official travellers, dating to around 72 AD. This building stayed in use for some time and was periodically redecorated. One later phase in the late second or early third century produced this very impressive recently uncovered mosaic, the largest found in London for more than 50 years.

Photo: Andy Chopping; © Museum of London Archaeology

The find offers fresh evidence of the ways that artistic influences from abroad have fed into London’s cultural life ever since it was established at an important crossing point on the navigable Thames shortly after the Roman invasion of Britain. Destroyed under Boudicca’s revolt in 60–61, the city later prospered as Rome consolidated its grip on the island and pushed the frontier of empire northwards, eventually to Hadrian’s Wall and beyond. Although London was never in the first rank of Roman cities – it never acquired an aqueduct, for example – it was large and prosperous enough to generate a fine range of public and private buildings.

As a port linking Britain to the continent it was an important entry point for the tastes, fashions, material and personnel which were an important part of Rome’s appeal to parts of the conquered British population. The Roman historian Tacitus memorably described how, as the military governors of the island ‘gave private encouragement and public assistance to the building of temples, forums, and private houses […] an esteem sprang up for our style of dress, and the toga became fashionable. Step by step [the Britons] were led to things which dispose to vice: porticoes, bathing, the elegance of banquets. All this in their ignorance, they called civilisation, when it was in reality a part of their servitude.’

Unguentarium (bottle for scented oils), found during the excavations. Photo: Andy Chopping; © Museum of London Archaeology

Despite Tacitus’ mordant take on the trappings of Roman ‘civilisation’, it seems that Roman material luxury was genuinely popular in its subject provinces. And why not? A colourful mosaic pavement laid over a suspended, heated floor was a practical comfort in a damp and chilly island. Its cheerfully regular patterns suggested a well ordered, cultured, and prosperous household. The rooms it furnished, whether used for private luxury or public display (or both), provided those who could afford it with a distinctive and comfortable way of life.

The Southwark mosaic is conspicuous both for its size and quality. It includes two highly-decorated panels set within a floor comprised of red tesserae. Fragments of brightly painted wall plaster suggest that the room in which the mosaic was located was also highly decorated. Romans used high-status decorations in rooms where they entertained, and mosaics, which can easily be swept or cleaned, are practical in such spaces; this one may well have been a triclinium or dining room.

Decorated wall plaster found during the excavations. Photo: Andy Chopping; © Museum of London Archaeology

The larger panel has colourful stylised flowers set within black and white guilloche borders and chequers, with a red and white guilloche framing the whole. To one side there is a pattern known as Solomon’s knot, a cross shaped formed of two interlinking loops. This larger panel shows similarities to other floors laid by a local team of Londinium mosaicists, the ‘Acanthus Group’, who developed their own variants of these typical elements: a sign of enough demand to fuel a local interior decoration industry, drawing on fashionable Roman designs.

The second, smaller panel tells a slightly different story. This has two more Solomon’s knots, framed by groups of shield-shaped pelta motifs and more flower elements. According to David Neal, formerly of English Heritage, the design of this panel is very similar to mosaic work from Trier, one of the most significant towns in Roman Germany. It suggests the movement of craftsmen between the two provinces, reminding us once more of Londinium’s history of cultural and economic exchange with its European neighbours.

Matthew Nicholls is Senior Tutor of St John’s College, Oxford, and Visiting Professor of Classics at the University of Reading.

Share

Recommended for you

The tomb of Rome’s first emperor at last reveals its secrets

The restored tomb of Augustus reopened this month – and an extensive new website gives a good sense of what has happened to it over the last two thousand years

Pilgrims and parrots in Jordan’s city of mosaics

Madaba preserves traces of the ancient Greek-Christian culture of the Middle East

That’s the spirit – how the Romans imagined the dead

The various ways in which the ancient Romans depicted figures from the afterlife tell us much about contemporary preoccupations