Sport nowhere for most of last year – and now sport everywhere. The 2020 Olympics are ready to roll in Tokyo this July and the Euros are about to get interesting. And then there’s Wimbledon, and the Ryder Cup to come, and some tedious 100-ball cricket competition that, well, is just not cricket. There is some decent sport art out there, we promise…

Football

‘The Beautiful Game’ it may be, but decent artworks depicting scenes from football tend to be thin on the ground. Perhaps it’s because a clean sheet is anathema to a painter; perhaps just because the parabola of a ball arcing into the top corner from outside the box is already a kind of art rather than a subject for it. Still, there are those who have harnessed the sheer visibility of the sport for grand artistic statements – in 2019, the Swiss curator Klaus Littmann planted 3,000 trees in the Austrian national stadium in what he called a ‘memorial’ to our environment. OOF, the art and football magazine, has just opened a gallery inside the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium at White Hart Lane, with its inaugural show of sculptures (‘BALLS’) featuring artists including Sarah Lucas and Hank Willis Thomas.

There are a few earlier artists who’ve gone against the run of play. Umberto Boccioni’s Dynamism of a Soccer Player (1913), among the finest works of his Futurist years, dissolves all save the footballer’s calf muscle into a whorl of vivid colour – the world in motion, so to speak. L.S. Lowry – a lifelong Manchester City fan – painted numerous matches, but it’s his Going to the Match (1953) that the Professional Footballers’ Association called ‘our prized possession’ after buying it at Christie’s for £1.9m in 1999. To my mind, there’s no painting that better communicates the force exerted by a stadium on match day, Lowry’s signature stick-people pulled towards it like iron filings toward a magnet. Samuel Reilly

Dynamism of a Soccer Player (1913), Umberto Boccioni. Museum of Modern Art, New York

Running

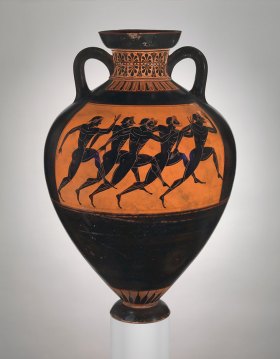

Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora (c. 530 BC), attributed to the Euphiletos Painter. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

When Baron de Coubertin sought to revive the spirit of classical Greece in the modern age, it was the Olympic Games he chose to resurrect. However, the ancient Greek sports fan had several other athletics competitions to follow – and gods to honour. While the games at Olympia were dedicated to Zeus and the only prize was a wreath made of olive leaves, it was Athena who was honoured at the Panathenaic Games, a more local event in Athens, where the winners of contests could expect to go home with amphoras full of valuable olive oil. This black-figure vase attributed to the Euphiletos Painter may show the runners vying for first place, but it also makes athletics in the 6th century BC seem like an effortlessly graceful affair.

The 20th-century runners Robert Delaunay depicted in a series of paintings in the mid 1920s are a more earthbound bunch. Unlike their monochrome and naked classical counterparts, running past us in profile, Delaunay’s faceless subjects tend to wear colourful kit and are usually headed straight for the viewer, as in this version recently sold at Christie’s. Fatema Ahmed

Les Coureurs (1930), Robert Delaunay. Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd 2021

Tennis

When Sir John Lavery painted The Tennis Party in 1885, the modern incarnation of the sport, known as lawn tennis, was only a decade or so old – but already hugely popular as a social as well as sporting event. This is reflected in Lavery’s sun-dappled scene, in which a small and smartly dressed audience gathers to watch a game of mixed doubles. The unruffled composure of these early players and their observers (if there’s any sweat, you certainly can’t see it) chimes closely with our own idealisation of the sport: the dazzling all-white uniforms, the endless strawberries and cream.

Although similarly pristine in their own way, Jonas Wood’s recent tennis-court paintings (on view at Gagosian in New York until 16 July) are entirely unpeopled. Instead, the American artist treats the court as a ‘geometric puzzle’, making sketches while watching the matches on TV and then later working them up into large, brightly coloured paintings. The flattened shapes and patterns remind me of the digital renderings that appear on screen after an umpire or line judge’s call is challenged. In fact, Wood has framed some of his court scenes with various objects from his studio – plants and flowers, a basketball – which serve as a reminder that when most of us watch the tennis, we don’t have a courtside seat. Gabrielle Schwarz

The Tennis Party (1885), John Lavery. Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

Croquet

A game you can play on a lawn on a warm summer’s evening, drink in hand between turns – that’s my kind of sport. A game of which you could justifiably ask ‘Is it even a sport?’ – now that really is the beautiful game. Croquet requires just enough physical effort to make it qualify as a sport under dictionary definitions but, crucially, not so much that you can’t play it in crinolines. Manet illustrated this in his Impressionist painting A Game of Croquet from 1873, the year in which he worked for the first time en plein air. The subject allowed the painter to demonstrate his handling of light and shade in an outdoor setting, but it also seems to play with our expectations of what such a bourgeois scene should represent: the figures are not in fact two married couples, but Manet’s friends Paul Roudier and the artist Alfred Stevens with the Impressionist models Alice Lecouvé and Victorine Meurent.

Alice holding her flamingo, John Tenniel’s illustration for Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (1865)

With its watering can as obstacle, its long grass and uneven surface, Manet’s croquet lawn isn’t far off the less-than-ideal setup in Alice in Wonderland: ‘Alice thought she had never seen such a curious croquet-ground in her life; it was all ridges and furrows; the balls were live hedgehogs, the mallets live flamingoes, and the soldiers had to double themselves up and to stand on their hands and feet, to make the arches.’ Lewis Carroll’s original illustrator, John Tenniel – previously of Punch fame – was meticulously faithful to the text, and here captures Alice on the verge of laughter as she struggles with her impossible feathered mallet. With one foot on her own curled-up hedgehog, she is poised to croquet the Queen’s hedgehog, which alas is already shuffling away. With that much physical exertion, Carroll’s version of croquet looks a little too much like real sport to me. Sophie Barling

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)