In its day, the House of Neptune in Pompeii was magnificent. Upon entering its atrium and approaching the pool of rainwater that collected there, you would have had at least seven choices as to where to go next. It is doubtful you would have noticed the doorway to the immediate right of the entrance. In fact, you would have had to turn back on yourself to walk through it, and not even Alice in Wonderland was inclined to do that.

At some point prior to the 12th of March this year, though, a bandit crept in to the room, which used to be a bedroom, and removed a 20cm section of plaster from its west wall. That section came from a painted vignette depicting the divine siblings Apollo and Artemis.

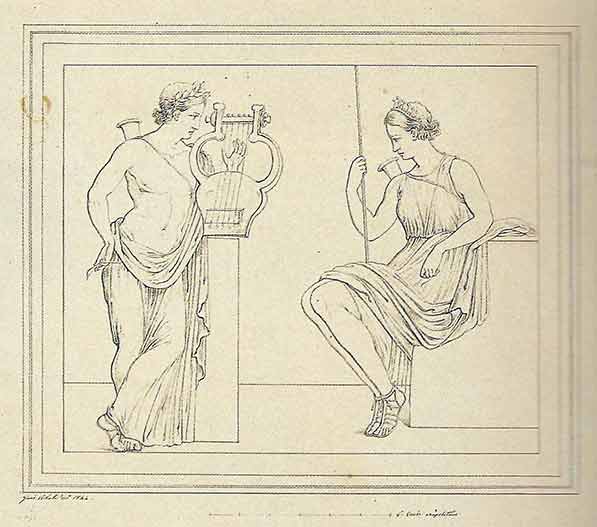

While not the finest wall painting among the houses of Pompeii, nor the best preserved (it is in fact barely visible today), it did have some merit. The blues and pinks would once have been quite vibrant. Apollo, god of music and the arts (not to forget our magazine), stands beside a podium, on which he rests his lyre. He looks at Artemis, who was depicted sitting down, eyeing her spear pensively, with her quiver slung over her right shoulder.

When the House of Neptune was excavated in the mid 19th century, the artist Giuseppe Abbate made a drawing of this wall painting, without which one could barely appreciate what was stolen, and what now remains. Stolen is Artemis from the waist up. This thief couldn’t even be bothered to take her in her entirety. Remaining are Apollo and the bend in Artemis’ knees – amply shown off by the fact that her drapery rather sexily skims her thighs – and her wonderfully tense calves. Her sandal-shod feet are portrayed with their heels off the ground so as to accentuate her muscles. She was, after all, the goddess of the hunt.

Guiseppe Abbate’s drawing of the fresco. From Pompeii Pitture e Mosaici Vol IV

Sure, there are better examples of Fourth Style wall paintings, the theatrical, trompe l’oeil paintings typically found in houses between AD 60 and the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. The House of the Vettii nearby, for example, has some exquisite frames interspersed with bold architectural panels and masks. But this painting was never intended to be the flashiest. It sits in one of the more modest bedrooms, low down on the back wall, beneath a window, and somewhat in the shadow of a niche that was painted with splendid green foliage.

Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, the foremost expert on the houses at Pompeii, tells me, ‘Ironically, this is probably the first time anybody has taken any notice of this painting. The loss is not in itself grave. What is alarming is the implication that, despite a system of partial video surveillance, it is possible for this sort of wanton damage to be done on site’.

The modesty of the piece no doubt contributed to its disappearance. Having seen complete frescoes on museum walls, a potential thief might well have believed its removal in one piece would be easy. It was not. It required time, patience, and, if he succeeded in keeping the painting intact, skill. Particularly since the building has been closed to the public, the culprit knew that it was unlikely that the theft would be noticed for some time. The missing fragment is ripe for conservation and repainting, which makes it a more likely candidate for sale than more celebrated Pompeian wall paintings.

Alternatively, if someone wanted to make a point about the lack of security and allocated funds so far spent on preserving the ancient sites, one can hardly think of a likelier theft. Only recently, a fragment of a wall painting from the House of the Orchard, previously stolen from a restoration laboratory, was returned anonymously by post. So long as the Carabinieri keep up their investigation, there is hope for poor Artemis yet.

But regardless of the outcome, whether it is heavy rain collapsing its ancient walls, or chancers taking to its most private cubicula with silver chisels, the picture of Pompeii crumbling before our eyes simply refuses to go away.

I am grateful for the assistance of Professor Wallace-Hadrill, who also sourced the drawing for this post.

Lead image: used under Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0)

On the Stolen Pompeii Fresco

Photo: Kim Traynor/Wikimedia Commons

Share

In its day, the House of Neptune in Pompeii was magnificent. Upon entering its atrium and approaching the pool of rainwater that collected there, you would have had at least seven choices as to where to go next. It is doubtful you would have noticed the doorway to the immediate right of the entrance. In fact, you would have had to turn back on yourself to walk through it, and not even Alice in Wonderland was inclined to do that.

At some point prior to the 12th of March this year, though, a bandit crept in to the room, which used to be a bedroom, and removed a 20cm section of plaster from its west wall. That section came from a painted vignette depicting the divine siblings Apollo and Artemis.

While not the finest wall painting among the houses of Pompeii, nor the best preserved (it is in fact barely visible today), it did have some merit. The blues and pinks would once have been quite vibrant. Apollo, god of music and the arts (not to forget our magazine), stands beside a podium, on which he rests his lyre. He looks at Artemis, who was depicted sitting down, eyeing her spear pensively, with her quiver slung over her right shoulder.

When the House of Neptune was excavated in the mid 19th century, the artist Giuseppe Abbate made a drawing of this wall painting, without which one could barely appreciate what was stolen, and what now remains. Stolen is Artemis from the waist up. This thief couldn’t even be bothered to take her in her entirety. Remaining are Apollo and the bend in Artemis’ knees – amply shown off by the fact that her drapery rather sexily skims her thighs – and her wonderfully tense calves. Her sandal-shod feet are portrayed with their heels off the ground so as to accentuate her muscles. She was, after all, the goddess of the hunt.

Guiseppe Abbate’s drawing of the fresco. From Pompeii Pitture e Mosaici Vol IV

Sure, there are better examples of Fourth Style wall paintings, the theatrical, trompe l’oeil paintings typically found in houses between AD 60 and the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. The House of the Vettii nearby, for example, has some exquisite frames interspersed with bold architectural panels and masks. But this painting was never intended to be the flashiest. It sits in one of the more modest bedrooms, low down on the back wall, beneath a window, and somewhat in the shadow of a niche that was painted with splendid green foliage.

Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, the foremost expert on the houses at Pompeii, tells me, ‘Ironically, this is probably the first time anybody has taken any notice of this painting. The loss is not in itself grave. What is alarming is the implication that, despite a system of partial video surveillance, it is possible for this sort of wanton damage to be done on site’.

The modesty of the piece no doubt contributed to its disappearance. Having seen complete frescoes on museum walls, a potential thief might well have believed its removal in one piece would be easy. It was not. It required time, patience, and, if he succeeded in keeping the painting intact, skill. Particularly since the building has been closed to the public, the culprit knew that it was unlikely that the theft would be noticed for some time. The missing fragment is ripe for conservation and repainting, which makes it a more likely candidate for sale than more celebrated Pompeian wall paintings.

Alternatively, if someone wanted to make a point about the lack of security and allocated funds so far spent on preserving the ancient sites, one can hardly think of a likelier theft. Only recently, a fragment of a wall painting from the House of the Orchard, previously stolen from a restoration laboratory, was returned anonymously by post. So long as the Carabinieri keep up their investigation, there is hope for poor Artemis yet.

But regardless of the outcome, whether it is heavy rain collapsing its ancient walls, or chancers taking to its most private cubicula with silver chisels, the picture of Pompeii crumbling before our eyes simply refuses to go away.

I am grateful for the assistance of Professor Wallace-Hadrill, who also sourced the drawing for this post.

Lead image: used under Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Share

Recommended for you

Ideal Man

The Musée d’Orsay’s exhibition of male nudes is almost a great show, but it misses a timely opportunity to explore homoerotic sentiment in art

Book Competition

Answer a simple question for a chance to win ‘Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino: Diverging Paths of Mannerism’

Affected Taste: William Kent at the V&A

How do you like your Georgians? William Kent’s designs come with a liberal coating of gilt