There are hundreds of exceptional artworks adorning the stands at TEFAF Maastricht this year. Everyone will have their own favourites, but we urge any visitor to seek out these works, which happen to be some of ours…Maggie Gray selects her TEFAF Treasures

Tree (1908), Piet Mondrian

Haboldt & Co

Haboldt & Co. specialises in Old Master paintings and works on paper – so it was something of a surprise to find a Mondrian on their TEFAF stand. The small but striking painting of a tree from 1908 marks the point at which the artist first began to turn from figurative art to abstraction. You can almost see the modernist grid emerging out of the landscape: in the lower half of the composition, rough horizontal bands of deep mauve paint stack up to the horizon; the tree itself glows amber in front of an indigo sky; and right down the centre of it, Mondrian has dragged a dark vertical column of paint.

Haboldt & Co. specialises in Old Master paintings and works on paper – so it was something of a surprise to find a Mondrian on their TEFAF stand. The small but striking painting of a tree from 1908 marks the point at which the artist first began to turn from figurative art to abstraction. You can almost see the modernist grid emerging out of the landscape: in the lower half of the composition, rough horizontal bands of deep mauve paint stack up to the horizon; the tree itself glows amber in front of an indigo sky; and right down the centre of it, Mondrian has dragged a dark vertical column of paint.

Framed in white (instead of Haboldt’s customary black), and unapologetically modern, it ought to look completely out of place on the stand. But somehow its dark but luminous colours, its small scale and its ordered composition are a good match for the meticulous still lifes and religious paintings either side of it. ‘We occasionally buy 19th- and early 20th-century pieces but only when they’re really special’, explained Carlo Van Oosterhout. Mondrian kept this piece in his studio for several years before giving it to a friend, suggesting that he, too, saw something in it – as did whoever snapped it up from the fair on the opening night.

Framed in white (instead of Haboldt’s customary black), and unapologetically modern, it ought to look completely out of place on the stand. But somehow its dark but luminous colours, its small scale and its ordered composition are a good match for the meticulous still lifes and religious paintings either side of it. ‘We occasionally buy 19th- and early 20th-century pieces but only when they’re really special’, explained Carlo Van Oosterhout. Mondrian kept this piece in his studio for several years before giving it to a friend, suggesting that he, too, saw something in it – as did whoever snapped it up from the fair on the opening night.

A Painter’s Cabinet (17th century), Adriaen van Stalbempt. De Jonckheere Master Paintings

A Collector’s Cabinet (17th century)

Adriaen van Stalbempt

De Jonckheere Master Paintings

This painting of well-dressed visitors poring over valuable art objects could hardly be better suited to TEFAF 2015. In 17th-century Flanders – as today – to possess a cabinet of curiosities was a sign of both wealth and refinement, and there’s a surplus of both on display here. In the near right corner a group of men inspect scientific specimens and treatises. By the door is a selection of musical instruments; fragments of classical sculpture sit in the near left corner; and the far wall is packed with paintings, several of which seem to mimic extant works by the likes of Peter Neefs, Snijders, and Adam Willaerts.

The (unidentified) figures in this sumptuous interior, which could be a collector’s private home or a dealer’s gallery, are clearly a cultivated crowd. But right in the centre of the room, two of them consider a painting with a rather subversive twist. In it, a group of men with animal heads smash the objects that the rest hold so dear. A warning against brutish ignorance, perhaps – but is it coincidence that they are dressed so similarly to the refined men in the room?

Adriaen van Stalbempt’s painting has been given pride of place on De Jonckheere’s stand. Whoever does take it home will be in good company: a similar example by the artist is in the Prado in Madrid.

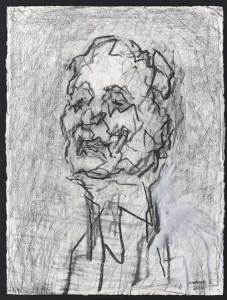

Self-Portrait III (2014)

Frank Auerbach

Malborough, London

Self-portrait III (2014), Frank Auerbach.

Until recently, Auerbach rarely turned his hand to self-portraiture. But now, at the age of 83, he has done quite a few, and I find this one – a large graphite and chalk study on paper – captivating. Auerbach’s characteristically wavering line, which refuses to trace the contours of a face in the traditional fashion and instead ranges over it in restless, exploratory touches, introduces a sense of vulnerability to the image, despite the confidence suggested in the turn of his head. He seems to flicker in and out of focus – unmistakeable but curiously indefinable, which is a rather neat reflection of the elusive nature of portraiture more generally. It more than holds its own with the highly finished, colourful works on the surrounding stands.

A triptych of the Virgin and Child in a Church, with the Nativity and a kneeling donor accompanied by standing Saints (c. 1500), The Master of 1499, Southern Netherlands, probably Ghent. Sam Fogg, London

A triptych of the Virgin and Child in a Church, with the Nativity and a kneeling donor accompanied by standing saints (c. 1500), The Master of 1499, Southern Netherlands, probably Ghent

Sam Fogg, London

It was the jewel-like intensity of the colours that first drew me to this northern Renaissance triptych on Sam Fogg’s stand, and its complex iconography that kept me there. Attributed to a little-known but clearly very accomplished artist known as The Master of 1499, it consists of five painted panels (the folding wings are worked on both sides) and is packed with religious symbolism.

The central panel shows the Virgin and Child in a Romanesque church (potentially the church of Saint Nicholas in Ghent, which it may have been commissioned for), accompanied by angels carrying the signs of the Passion. On the left is a Nativity; on the right, the donor looks on in worship flanked by four saints; and on the reverse, two grisaille panels depict the Annunciation. On top of the more obvious symbols are the more obscure: the Christ child has counted out three rosary beads (an echo of the three nails presented by the angel to his left?) and the Virgin wears a deep red robe instead of the customary blue, perhaps symbolising the blood of Christ. Such rich symbolism is enabled – and enhanced – by the wealth of exquisite detail that the artist has introduced into each scene. I could pore for hours over the different textures, patterns and ornamentation that are worked into this busy but balanced composition.

The central panel shows the Virgin and Child in a Romanesque church (potentially the church of Saint Nicholas in Ghent, which it may have been commissioned for), accompanied by angels carrying the signs of the Passion. On the left is a Nativity; on the right, the donor looks on in worship flanked by four saints; and on the reverse, two grisaille panels depict the Annunciation. On top of the more obvious symbols are the more obscure: the Christ child has counted out three rosary beads (an echo of the three nails presented by the angel to his left?) and the Virgin wears a deep red robe instead of the customary blue, perhaps symbolising the blood of Christ. Such rich symbolism is enabled – and enhanced – by the wealth of exquisite detail that the artist has introduced into each scene. I could pore for hours over the different textures, patterns and ornamentation that are worked into this busy but balanced composition.

TEFAF Maastricht is at the Maastricht Exhibition & Congress Centre from 13–22 March.

Related Articles

TEFAF Treasures: Digby Warde-Aldam

TEFAF 2015: Susan Moore previews the Maastricht fair

Beyond TEFAF: what else is there to see in the region this month?

Click here to buy the current issue of Apollo for more TEFAF highlights

TEFAF Treasures

A triptych of the Virgin and Child in a Church, with the Nativity and a kneeling donor accompanied by standing Saints (c. 1500), The Master of 1499, Southern Netherlands, Brussels. Sam Fogg, London

Share

There are hundreds of exceptional artworks adorning the stands at TEFAF Maastricht this year. Everyone will have their own favourites, but we urge any visitor to seek out these works, which happen to be some of ours…Maggie Gray selects her TEFAF Treasures

Tree (1908), Piet Mondrian

Haboldt & Co

A Painter’s Cabinet (17th century), Adriaen van Stalbempt. De Jonckheere Master Paintings

A Collector’s Cabinet (17th century)

Adriaen van Stalbempt

De Jonckheere Master Paintings

This painting of well-dressed visitors poring over valuable art objects could hardly be better suited to TEFAF 2015. In 17th-century Flanders – as today – to possess a cabinet of curiosities was a sign of both wealth and refinement, and there’s a surplus of both on display here. In the near right corner a group of men inspect scientific specimens and treatises. By the door is a selection of musical instruments; fragments of classical sculpture sit in the near left corner; and the far wall is packed with paintings, several of which seem to mimic extant works by the likes of Peter Neefs, Snijders, and Adam Willaerts.

The (unidentified) figures in this sumptuous interior, which could be a collector’s private home or a dealer’s gallery, are clearly a cultivated crowd. But right in the centre of the room, two of them consider a painting with a rather subversive twist. In it, a group of men with animal heads smash the objects that the rest hold so dear. A warning against brutish ignorance, perhaps – but is it coincidence that they are dressed so similarly to the refined men in the room?

Adriaen van Stalbempt’s painting has been given pride of place on De Jonckheere’s stand. Whoever does take it home will be in good company: a similar example by the artist is in the Prado in Madrid.

Self-Portrait III (2014)

Frank Auerbach

Malborough, London

Self-portrait III (2014), Frank Auerbach.

Until recently, Auerbach rarely turned his hand to self-portraiture. But now, at the age of 83, he has done quite a few, and I find this one – a large graphite and chalk study on paper – captivating. Auerbach’s characteristically wavering line, which refuses to trace the contours of a face in the traditional fashion and instead ranges over it in restless, exploratory touches, introduces a sense of vulnerability to the image, despite the confidence suggested in the turn of his head. He seems to flicker in and out of focus – unmistakeable but curiously indefinable, which is a rather neat reflection of the elusive nature of portraiture more generally. It more than holds its own with the highly finished, colourful works on the surrounding stands.

A triptych of the Virgin and Child in a Church, with the Nativity and a kneeling donor accompanied by standing Saints (c. 1500), The Master of 1499, Southern Netherlands, probably Ghent. Sam Fogg, London

A triptych of the Virgin and Child in a Church, with the Nativity and a kneeling donor accompanied by standing saints (c. 1500), The Master of 1499, Southern Netherlands, probably Ghent

Sam Fogg, London

It was the jewel-like intensity of the colours that first drew me to this northern Renaissance triptych on Sam Fogg’s stand, and its complex iconography that kept me there. Attributed to a little-known but clearly very accomplished artist known as The Master of 1499, it consists of five painted panels (the folding wings are worked on both sides) and is packed with religious symbolism.

TEFAF Maastricht is at the Maastricht Exhibition & Congress Centre from 13–22 March.

Related Articles

TEFAF Treasures: Digby Warde-Aldam

TEFAF 2015: Susan Moore previews the Maastricht fair

Beyond TEFAF: what else is there to see in the region this month?

Click here to buy the current issue of Apollo for more TEFAF highlights

Share

Recommended for you

First Look: Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit

In one remarkable year, Rivera arguably made his greatest mural cycle and Kahlo forged her own expressive style

Ghost House

Rachel Whiteread’s ‘House’ was unveiled 20 years ago today. It stood for barely three months, but its influence endures

Regional museums are in crisis. Can they survive?

Key speakers debated the issue at a Courtauld event this week