Shot between 2011–16, Chloe Dewe Mathews’ Thames Log traces the world-famous river from its easily missed, disputed source in a field in Gloucester to its more expansive end in the North Sea. The photographer focuses on rituals, from baptism to pagan ceremonies, and from reading the Sunday paper to teenage rites of passage, and in doing so, she suggests something paradoxical. Just as rituals are repetitive but never quite the same, the Thames is both centuries old and ever-changing.

‘Heraclitus’ axiom that you can’t step into the same river twice has become so familiar that it’s hard to look at what it means,’ writes Marina Warner, in her introduction to the book. With Thames Log, Dewe Mathews tries to do just that. ‘The things people do on the river reflect, and have always reflected, the age in which they happen,’ she tells me. ‘That said, water often seems to inspire a kind of free, open-ended mode of behaviour that life on soil and concrete doesn’t permit; things on land are rooted where, by comparison, aqueous activity can have a kind of timelessness.’

Pagan River Ritual, Oxford (2013) in ‘Thames Log’ by Chloe Dewe Mathews. @ Chloe Dewe Mathews

This ebb and flow, that movement between the temporary and the timeless, is reflected in her images, which are at once shots of particular moments and recordings of ongoing acts. There are photographs of commuters crossing London Bridge, for example; captured on 9 February 2016 but also redolent of the crowd in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, first published nearly a century before. Thames Log, as the name suggests, is an exacting record, including the time, date, coordinates and tidal and weather conditions at which each image was made. But it also includes runs of images, multiple shots that undercut the notion of the decisive moment. There’s this, the book suggests, but then there’s this and this and this. Like water, time proves elusive. It is difficult to grasp, even slippery.

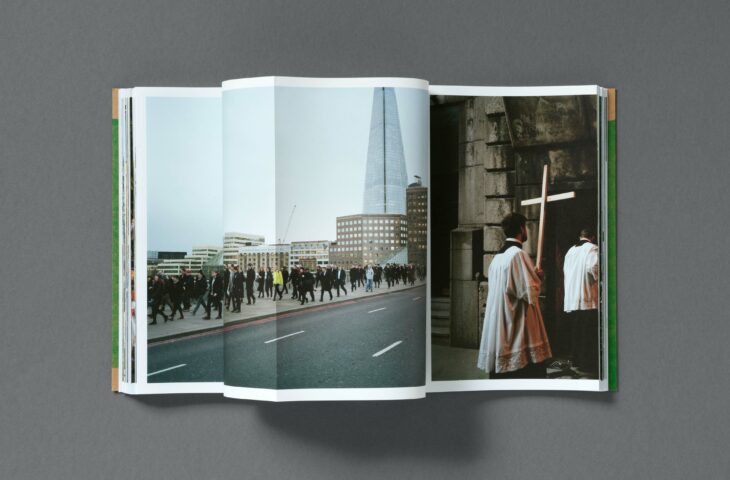

Spread from Thames Log by Chloe Dewe Mathews

The design of the book emphasises this quality because, rather than allotting one page per picture, it uses a French fold to allow the images to flow from one spread to another. ‘The water that flows through the capital avoids having specific, rigid parameters imposed upon it,’ says Dewe Mathews; in this book her photographs do the same. ‘I made it clear that I was interested in making an artist book, whose design and format would be closely informed by the content,’ the photographer explains, of her relationship with the publishing house Loose Joints (the book is co-published with the Martin Parr Foundation, which also plans to show Thames Log at its Bristol gallery in summer). ‘I sent them [Loose Joints] a wide edit of photographs and suggested we use sequences of images as a way of giving still photographs a flow, movement and sense of passing time. We worked together on the edit and they came up with the idea of a French fold book, with images spilling over the pages, to create a kind of rolling liquidity through the series.’

Dewe Mathews has often explored photography’s interesting relationship with time in her work. Her series Shot at Dawn (2013) shows the now-quiet locations in which First World War deserters were executed, for example, and was included in the Tate Modern’s exhibition ‘Conflict, Time, Photography’ in 2014/15; her book In Search of Frankenstein (2018) – with its Proustian title – finds contemporary parallels in Mary Shelley’s 200-year-old novel. ‘Her practice explores ways in which photography can project the past on to the present, allowing for time to be expanded and contracted and multiple narratives to be explored side by side,’ wrote Shoair Mavlian, director of Photoworks, in an essay about Dewe Mathews’ work For A Few Euros More, which was shown at Fondazione MAST, Bologna last year.

Ceremonial Boat Burning, Oxford (2013) in ‘Thames Log’ by Chloe Dewe Mathews. © Chloe Dewe Mathews

Thames Log is also a record of contemporary Britain’s social spread, from London’s Thamesmead estate to the spires of Oxford (where, as Warner points out, a rowing team is burning a boat – ‘a beautiful work of craftsmanship […] which costs so much that many rowing clubs can’t afford one’). En route it presents the multicultural nature of modern Britain, from a Muslim couple quietly observing evening prayer at Southend on Sea to the Blessing of the River at London Bridge at Epiphany. ‘Traditionally, I think the Thames is perceived as a playground for genteel rowing clubs on the one hand, and as a relic of Britain’s industrial past on the other,’ says Dewe Mathews. ‘I wanted to present a more nuanced view.’

Times do change, however, no matter how exact the coordinates and it’s fitting that Thames Log is of its time – even now recording a past era, though the images were completed so recently. Social movements such as Black Lives Matter are helping bring neglected narratives into focus; less positive changes, such as the terrorist attacks on London Bridge and the emergence of Covid, mean that some of the scenes Dewe Mathews shot now look very different. The commuters, for the moment, are no longer flowing over London Bridge. ‘We both step and do not step in the same rivers,’ as Heraclitus put it; maybe you could also say, time and tide wait for no man.

Maghrib/Evening Prayer, Southend-on-Sea (2012) in ‘Thames Log’ by Chloe Dewe Mathews. © Chloe Dewe Mathews

Thames Log by Chloe Dewe Mathews is co-published by Loose Joints and the Martin Parr Foundation.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)