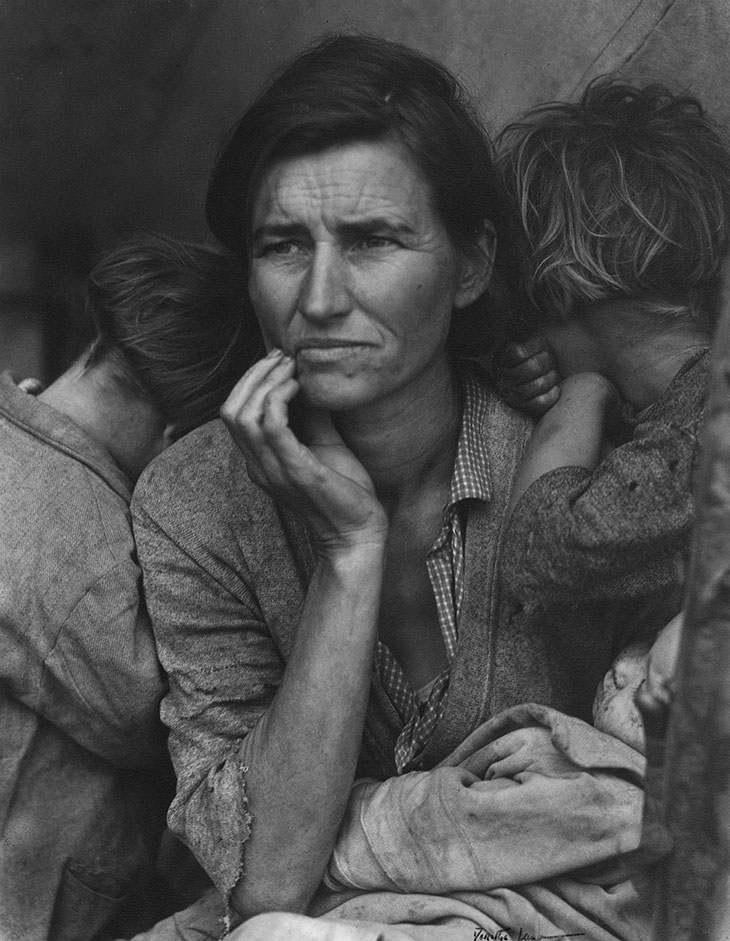

In an age increasingly plagued by the overuse of the word ‘iconic’, it is salutary to be reminded of what makes an image truly deserve the tag. Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936) is one of those photographs in which the combination of compositional brilliance, human empathy, and political significance makes for something simultaneously beautiful and searing. As David Campany points out, writing in the catalogue for the Barbican’s current Lange retrospective, images often become ‘iconic’ because they stand in as ‘default substitutes for the complexities of history’. This is doubtless true of Lange’s photo and Depression-era America. But if a photograph’s transformation into an icon is in some way an admission of failure in our attempts to comprehend history itself, I can think of few better admissions than this. Denuded of either false hope or the possibility of capitulation – two children clinging to a mother’s neck, a baby in her arms – it is the photographic equivalent of the Beckettian formula ‘I can’t go on, I’ll go on’.

MIgrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936), Dorothea Lange. © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

As the show’s title – ‘Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing’ – suggests, there is no such thing as a neutral eye, and Lange’s work was avowedly political in nature. ‘Everything’, she once said, ‘is propaganda for what you believe in’, and the camera was her method of disseminating it – an ‘instrument for teaching people to see’. From the 1930s to the end of Lange’s career in the ’60s, America provided no shortage of sights that many would have preferred to not see at all. The emergence of the visible effects of the Depression on the streets of San Francisco in 1933 drove Lange out of the studio and away from the dreamy pictorialism of her early work, documented in the first room of the show, in order to record the breadlines and demonstrations on the streets below. That year nearly 20 per cent of California’s population were on state or country relief of some form. Lange never really returned to the studio.

The next year saw the environmental catastrophe of the Dust Bowl storms. Under the aegis of the Resettlement Authority (later the Farm Security Authority) Lange and other photographers, among them Walker Evans, were sent out to record the lives of the vast transient and jobless population targeted for aid under Roosevelt’s New Deal. Between the spring of 1936, when she shot Migrant Mother, and autumn of the same year, Lange trekked, in the ballpark figure given by the catalogue, some 27,000 kilometres on assignment.

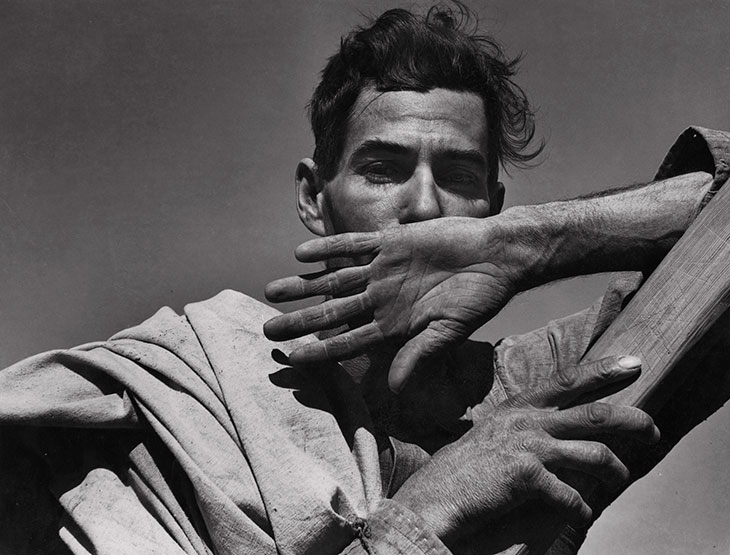

Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona (1940), Dorothea Lange. © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Her migrant worker photographs may be Lange’s best known work, but her pace never slackened. The next decade saw her recording the explosion of anti-Japanese sentiment in the wake of Pearl Harbour – one sign proclaiming ‘Japs Out’, another proclaiming ‘I AM AN AMERICAN’ – and the internment camps that followed. Her photographs documenting the boom years of the war economy in California’s shipyards are overhung by the sense of distance between the burgeoning female workforce and the older male dockers, with another fault line running between the races. Lange’s eye is never dour or moralising: her subjects tend to know they are being photographed, and there are smiles and pride in their faces. But there is no shying away from the fact that life is hard, and that most of it is beyond their control.

San Francisco, California. Flag of allegiance pledge… (1942), Dorothea Lange. Courtesy National Archives

The same feeling permeates ‘Vanessa Winship: And Time Folds’, running in the galleries directly above the Lange exhibition. It is a canny pairing on the part of the Barbican: two female photographers, both motivated by an urge to document the lives of people in the grip of forces more powerful than any individual, but entirely distinctive in their approaches. Winship’s work belongs more self-consciously to a tradition of fine art photography than Lange’s, which often had to satisfy the conditions of administrative record-keeping before attending to aesthetics, but it too is drawn to society in flux, and the differentials of uneven development and distribution. The contemporary British photographer also more than measures up to Lange in the breadth and depth of her skill and empathy.

As Winship’s first major solo outing in Britain, the exhibition has plenty of ground to cover, both geographically and temporally. Drawn to peripheries and hinterlands, Winship has spent much of her career on projects that explore memory and identity on the boundaries of Europe: in the Balkans, Turkey, and the Caucasus. The grainy, wide-angle black and white shots of ruined buildings, playing children, and life slowly returning to normal in Imagined States and Desires: A Balkan Journey (1999–2003), Black Sea: Between Chronicle and Fiction (2002–06), and the superb portrait series Sweet Nothings (2007) are enough to make you ask why it has taken so long for Winship to have a retrospective in this country.

Untitled, from the series Sweet Nothings: School Girls of Eastern Anatolia (2007), Vanessa Winship. © Vanessa Winship

Like Lange, Winship is able to pick individuals out of the mass, or rather to let individuals pick themselves out in front of the camera – a process most visible in Sweet Nothings’ black and white portraits of Turkish schoolgirls, posing in their uniforms. It is the small details, the ‘sweet nothings’ with which they customise their state-mandated dresses, that bring them together – and set them apart. It is an extraordinary series, exemplifying Winship’s ability to capture the interactions between personal and national pride. The same thread runs through Winship’s more recent work in the mixed landscapes and portraits of her American chronicle she dances on Jackson (2011–12), a series that forms a natural counterpart to Lange’s work downstairs.

Exhibitions can often run with slight desperation, harried by curators, after the figure of contemporary relevance. Here the viewer is left to draw their own parallels, and wisely too. In a world marked by mass migration, environmental catastrophe, economic isolationism and detainment camps, as the idea of any international political consensus falls to pieces, there is no need for the curators to say anything at all.

‘Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing’ and ‘Vanessa Winship: And Time Folds’ are at the Barbican, London, until 2 September.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)