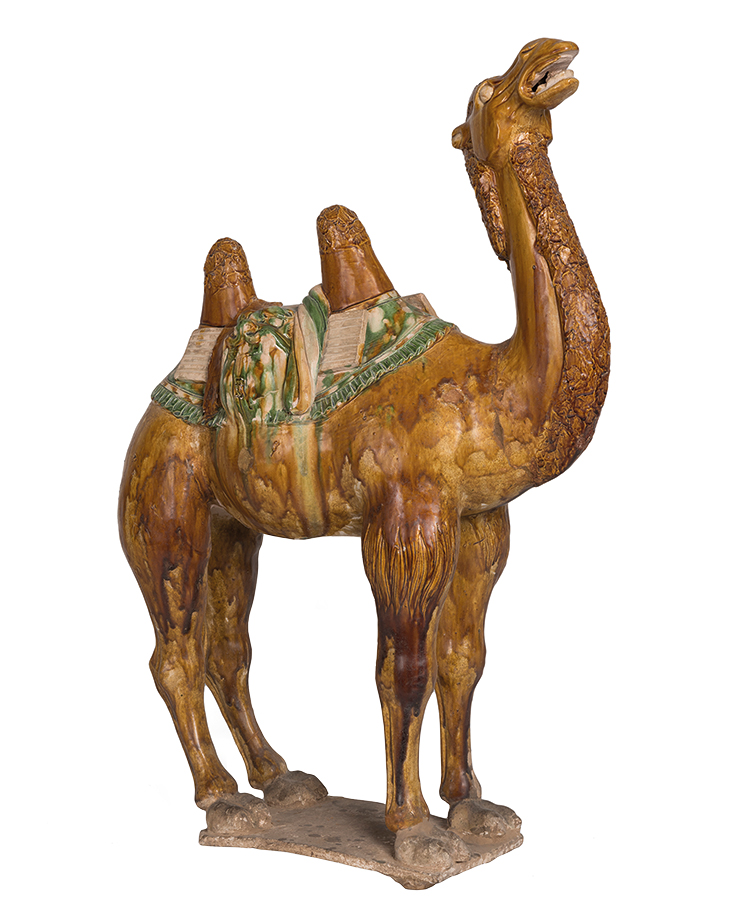

Turning the corner into the Burrell Collection’s long north-west gallery, its glass walls nestling against a forest of chestnut and sycamore in the heart of Pollok Country Park, Glasgow, visitors may find themselves face to face with a little earthenware camel from China: a proud Bactrian, huffing and snorting with a colourful saddle between its humps. The historian John Julius Norwich recalled an encounter with what may have been the very same ‘marvellous Tang camel’ ahead of the opening of the Burrell in 1983 – one of scores of ‘hidden miracles’ he watched being lovingly removed from their wrappers. –

The 9,000-piece-strong collection amassed by local shipping magnate Sir William Burrell over some 80 years and donated to the city of Glasgow – an act Glasgow University’s principal at the time, Hector Hetherington, described as ‘one of the greatest gifts ever made to any city in the world’ – returns to public view on 29 March, after a six-year renovation to the museum that was built for it. But if, in a sense, the ‘miracles’ are coming out of hiding once again, they emerge into a world much changed since 1983.

The Burrell Collection, Glasgow, photographed in February 2022 in the final stages of its renovations. Photo: Alan McAteer

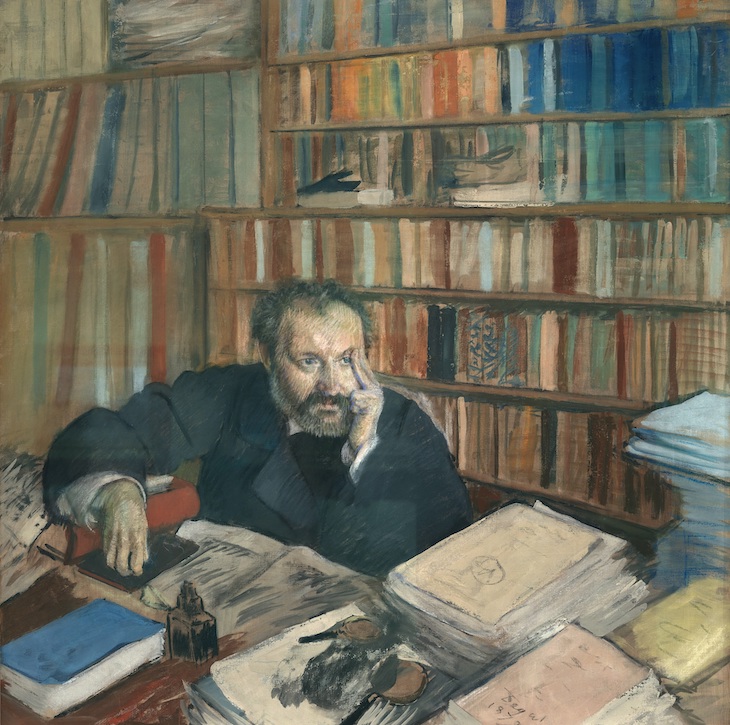

When Norwich was writing, the collection had languished in storerooms for a quarter of a century and its full scope and significance had become, beyond a small circle of initiates, little more than a rumour. This time around, during the closure, ambassadors from the collection have been sent to seek new audiences across the world. The Degas pastels travelled to the National Gallery in 2017; the Wagner Persian carpet, one of the oldest Islamic garden carpets in existence, to the Met the following year; highlights from the Impressionist collections toured to five galleries across Japan in 2019–20. In 2018, the first major catalogue of the European tapestries – to Burrell’s mind, the strongest section of his collection – was published. Far from being in hiding, these last few years the Burrell Collection has become more globally visible than ever – the result of an amendment to Burrell’s will, enabling loans to be made from the collection, which was pushed through the Scottish parliament in 2014, just before the renovations began. This was, moreover, a project born in a pre-Covid world, and new challenges have emerged in the years since ground was broken on the new Burrell.

From the outside, little has changed to Barry Gasson’s modernist structure of pine, glass and concrete – save that, where once there was a single entrance, through one of the Romanesque stone archways Burrell bought from William Randolph Hearst into a narrow corridor jutting out from the south wall, there is now a larger glass doorway opening onto the courtyard. It’s a symbol, in a sense, of greater accessibility; the redesign by John McAslan + Partners has been heavily informed by public consultation with 15,000 Glaswegians. Duncan Dornan, head of museums and collections at the council-owned charity Glasgow Life, tells me that the Burrell previously drew ‘a relatively narrow demographic compared to other museums in Glasgow’; in seeking to attract new audiences, he points to the example set by the civic-mindedness of Glasgow industrialists like Burrell and, before him, Archibald McLellan, in bequeathing their collections to the city.

Bactrian camel, Tang dynasty (618–907), China. Photo: © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collections

The collection itself has also been opened up, to visitors and scholars alike, as never before. A large concrete staircase now connects the ground floor with the basement, in which the storerooms are now fully accessible by appointment, and where one-way glass offers visitors a peek at the work of conservators. Overall, there is an additional 35 per cent of gallery space. Energy efficiency has been improved. Digital displays blink out at visitors from every corner.

It is, in short, a statement piece – a museum that is meant to be seen as having its eyes to the future, and one which, at £68.3m, has come at considerable public cost. Half of the capital has been fronted by Glasgow City Council – a governing body which, as any who has skirted the city’s cavernous potholes will attest, is not blessed with deep pockets. Glasgow Life’s income dropped by £38m during lockdown; programming for the other institutions managed by Glasgow Life, including the city’s flagship museum, the Kelvingrove, has all but frozen.

That so much should have gone into repackaging the collection of a Victorian industrialist for the 21st century might seem somewhat surprising – but then, the Burrell has long been a symbol with many sides in Glasgow. It is representative of an outward-facing internationalism – and not just because it offers a window on cultures spanning three continents and 5,000 years, but because of the global esteem in which the collection is held. In the fields Burrell most cherished, it ranks among – and sometimes surpasses – single-owner collections amassed by men of far greater means: Getty, or Hearst, or Huntington.

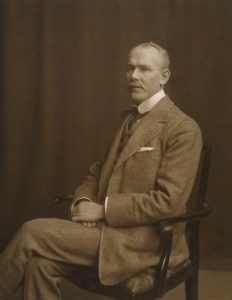

Sir William Burrell (c. 1906), T&R Annan and Sons. Photo: © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collections

But it is also emblematic of the city’s reckoning with its own chequered history. As such, the opening of the Burrell in 1983 was a curiously Janus-headed affair. On the one hand, it was a memorial to the endeavours of a man who seems so completely a product of the Victorian era that there is something hard to believe in the fact that he lived until 1958. When he was born, in 1861, Glasgow had recently been dubbed the second city of the British Empire – largely as a result of its shipbuilding industry, through which Burrell acquired his fortune. He bought his first picture in his teens, with money his father said would have been more wisely invested in a cricket bat. Though Burrell would later compile one of the finest collections of Degas’s pastels worldwide, as well as wonderful works by Sisley, Cézanne and Manet, his taste in paintings seems to have frozen in the 19th century; one looks in vain in the Burrell Collection for anything so modern as a Picasso.

By the time Burrell died at the age of 96, the shipyards were bankrupt and Glasgow was in a protracted and traumatic period of industrial decline. It was not until the 1980s that the city began to revive its economic fortunes; meanwhile, a wrangle between Burrell’s trustees and the council had played out. Burrell stipulated that his collection should be housed in a rural setting at least 16 miles from the centre of town, to protect it against pollution; it was only with the council’s acquisition of the Maxwell family’s Pollok estate in 1966 that a compromise was found, and plans towards the construction of the building could commence. The Burrell opened 17 years later – a moment that Bridget McConnell, chief executive of Glasgow Life, describes as Glasgow’s ‘first self-conscious act’ of cultural regeneration.

The Months: April (c. 1500), Southern Netherlands, possibly Tourney. Burrell Collection, Glasgow. Photo: © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collections

More than a million visitors flocked to the museum in its first year; McConnell tells me that its initial success was instrumental in the success of Glasgow’s bid for European City of Culture in 1990, a bid which she says brought ‘ridicule’ from some quarters given the city’s reputation for poverty and violence. Norwich described it as ‘the most important new museum to have been built in Britain since the South Kensington complex over a century ago’. But by 2015, the roof was leaking continually. Hostage to a somewhat rigid design, with many of the cases custom-built to house a single object, the museum could change its displays only infrequently. Visitor numbers dwindled. Bereft of a clear sense of how the museum might adapt to changing times, it gradually came to seem something of a hermit’s cave in the woods.

How, then, is the new museum presenting itself to the future? Much has been made of the digital displays – a means, Dornan says, of making available new layers of interpretation without ‘overwhelming’ the objects themselves. But much more significant is the greater prominence given to the character of Burrell himself. Just beyond the courtyard, an animated Burrell struts across a large screen with his umbrella in hand; nearby are displays of objects he lent to public institutions over the course of his career. Later this year, the Burrells will be the subject of the inaugural display in the new temporary exhibition space. Dornan suggests that this new focus on Burrell himself came about through audience research. ‘In allowing people to understand the range of the collection,’ he says, ‘it was important that they were able to understand it as the work of an individual.’

This rather flies in the face of Burrell’s own wishes. A private man, Burrell never commissioned his own portrait, and in fact Norwich suggests it was his ‘express wish’ that none hang in the museum that bears his name. He preferred to let the collection speak for itself. In the 14 years between 1944, when he signed his Deed of Gift to the city, and his death, Burrell added more than 2,000 items to his collection, focusing particularly on those areas he thought most in need of fleshing out – the ancient cultures of Assyria, Egypt, Greece and Rome. He thought of his collection, if not as comprehensive, then certainly as a holistic account of the development of civilisation from antiquity to the present. His success in this endeavour was remarkable – as the old Burrell, divided into galleries taxonomically, made clear – but it was an endeavour that bespeaks a particular, Victorian self-confidence, asserting a monolithic vision of history that has fallen out of fashion in recent years. In a sense, then, the focus on Burrell is a canny means of killing two birds with one stone. It helps new audiences to get a bearing on the collection. But it also underlines its nature not as an authoritative and impartial story of human civilisation but as the product of individual taste, toil, and the nous for scheming and haggling with which, as Kenneth Clark observed, he ‘outwitted art dealers’ on occasions ‘too numerous to be repeated’.

Head of Sekhmet (c. 1390–1352 BC), Egypt. Burrell Collection, Glasgow. Photo: © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collections

Two of the three period rooms from Burrell’s Berwickshire house at Hutton Castle have gone, but in fact, all of the remaining galleries have been rearranged to function more like a house museum. The much-loved north-west gallery – designed by the original architects as a ‘walk in the woods’, with objects of all times and places brought into surprising juxtapositions – has not only been retained here, along with the walkways on the south wall dotted with Burrell’s medieval glass, and the Romanesque, gothic and Renaissance portals built into the structure throughout; it has become the model. Galleries previously devoted to tapestries, or ‘Oriental art’, have been replaced by modular, thematic presentations. Dornan describes the new design as a reinterpretation of the stipulation in Burrell’s will that his collection be displayed ‘as in a private house’ – but it’s fair to say that it also follows firmly in a trend established by Tate Modern and, more recently, the rehang of MoMA in New York. Sections focus on topics such as animals, or gardens; in the latter, the Wagner garden carpet, now on permanent display for the first time, is shown alongside an exquisite cycle of early 16th-century Flemish tapestries depicting the Labours of the Months.

The new design will enable displays to rotate much more frequently – and McConnell points to the need, now more than ever, for museums to be ‘places that don’t stand still’. But, at least in its present incarnation, it is also clear that this is a museum trying hard to cater for school groups and scholars alike, balancing reverence with readability. Wall labels and digital displays both range wildly in register, offering a slightly unpredictable mélange of historical context and jeux d’esprit. The latter are often charming – I defy even the most po-faced museum-goer not to have a crack at trying to emulate the ‘strange’ expression of a 15th-century wooden angel from the Church of St Michael in Aughton – but sometimes cloying, shoe-horning in appeals to inclusivity that the objects don’t always support.

Rebecca Quinton, curatorial lead for the Burrell, suggests that the ‘connoisseurs know what they’re coming to see’. It’s a phrase which summons the amusing spectre of old-world savants fiddling irately around with LED screens, but which also raises the more disquieting image of the amateur historian, from any demographic, finding that they have to work rather harder here to round out an understanding of Iznik ware, or the medieval church, or the Impressionist movement. But Quinton is also quick to point out other ways that the collection is being mobilised to this end; the tapestries catalogue is to prove the prelude to an extensive publication schedule which, in the coming years, will see a new catalogue of Burrell’s French paintings and drawings, as well as volumes introducing other parts of the collection. Art historians will also be richly served in the basement, with its open-access stores, and upstairs, where what were once curatorial offices have been turned into a suite of new galleries exploring craftsmanship – playing to the strengths of a collection that is so profuse in ceramics, bronzes, silver, stained glass and textiles.

Portrait of Edmond Duranty (1879), Edgar Degas. Burrell Collection, Glasgow. Photo: © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collections

Still, it is fair to say that none of the money that has been spent, nor any of the decisions since made, have the potential to prove as momentous as the amendment to Burrell’s Deed of Gift passed in 2014. Glasgow has rarely had the ability to attract, or to fund, serious loan exhibitions with objects from international collections. ‘Let me be clear – that’s why we changed the will,’ McConnell says. ‘It was about reciprocity with world museums and researchers so that we could share the intellectual capital we both have.’ Like the similar decision to open up the Wallace Collection to lending in 2019, the move was not without its detractors – though McConnell is quick to point out that it was made with the blessing of Burrell’s trustees. It raises the tantalising prospect of seeing the masterpieces Burrell acquired, for the first time, alongside their peers from across the world; in this respect, the manner in which the Wallace has capitalised – for instance, by partnering with the National Gallery to reunite Rubens’s last landscapes after 400 years – should provide both an incentive and an example to the city of Glasgow.

This will, of course, need money behind it to make it work. McConnell, who is passing on the baton at Glasgow Life in May, speaks urgently of the need for ‘new funding models’: for a closer relationship with the UK Government (which provided £3m for the Burrell’s revenue stream last year), for a new openness to private sponsorship, and above all for a renewed show of faith from public coffers. In his declining years, Burrell himself wrote that ‘We cannot have too many exhibitions […] for the greater the number, the greater are our opportunities of becoming more closely acquainted with what is beautiful.’ If Glasgow can leverage the newly open collection to bring great works of art into the city from across the world, that is surely the best homage it can pay to his wishes and his example.

The Burrell Collection, Glasgow, is reopening on 29 March. For more information, visit www.burrellcollection.com.

From the March 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)