In autumn of 1852, Edward Lear was in Sussex. He had been hired to paint the fig tree in the garden of Frederick North, the MP for Hastings. But for North’s daughter, Marianne (destined to become a botanical painter herself), what stuck in the memory was Lear’s habit of turning up in the family sitting-room in the evening and singing lengthy original settings of Tennyson’s poems, ‘composing as he went on, and picking out the accompaniments by ear, putting the greatest expression and passion into the most sentimental words’. The performances were usually too much for Marianne, who would burst out laughing, whereupon Lear would substitute ‘Hey Diddle Diddle, the Cat and the Fiddle, or some other nonsensical words to the same air’, and sing the new words with the same pathos and ‘expression and gravity of face’. Even Victorian sentimentality, it appears, had its limits.

In autumn of 1852, Edward Lear was in Sussex. He had been hired to paint the fig tree in the garden of Frederick North, the MP for Hastings. But for North’s daughter, Marianne (destined to become a botanical painter herself), what stuck in the memory was Lear’s habit of turning up in the family sitting-room in the evening and singing lengthy original settings of Tennyson’s poems, ‘composing as he went on, and picking out the accompaniments by ear, putting the greatest expression and passion into the most sentimental words’. The performances were usually too much for Marianne, who would burst out laughing, whereupon Lear would substitute ‘Hey Diddle Diddle, the Cat and the Fiddle, or some other nonsensical words to the same air’, and sing the new words with the same pathos and ‘expression and gravity of face’. Even Victorian sentimentality, it appears, had its limits.

This is not Wilde snickering at the death of Little Nell – Lear is as comfortable with idleness as idle tears, and frequently found it difficult to choose between them. Indeed, the facility with which he slips from mood to mood suggests the ways pathos and gravitas might depend on each other. If such incongruous pairings as a cat and a fiddle are constitutive of nonsense, it is part of the brilliance of Jenny Uglow’s new biography of Lear to show that such odd conjunctions and metamorphoses also help us to make sense of Lear as an individual and an artist.

The incongruities stem in part, as Uglow notes, from the fact that Lear himself was not always certain of his direction. His admission, ‘I enjoy hardly any one thing on earth while it is present: – always looking back, or frettingly peering into the dim beyond,’ suggests that at times he had difficulty pinpointing himself in his own biographical imagination. Alienated from his parents, and routinely unsure about money, even the seemingly incidental personal obsessions charted by Uglow – Lear’s fascination with his own clumsiness and short-sightedness, for instance – can seem emblems of a sense of instability. And, like his Old Man in a boat who believes himself afloat (though he ‘ain’t’), it was at times unclear whether Lear was saturated by, or impermeable to, the atmosphere in which he moved.

The incongruities stem in part, as Uglow notes, from the fact that Lear himself was not always certain of his direction. His admission, ‘I enjoy hardly any one thing on earth while it is present: – always looking back, or frettingly peering into the dim beyond,’ suggests that at times he had difficulty pinpointing himself in his own biographical imagination. Alienated from his parents, and routinely unsure about money, even the seemingly incidental personal obsessions charted by Uglow – Lear’s fascination with his own clumsiness and short-sightedness, for instance – can seem emblems of a sense of instability. And, like his Old Man in a boat who believes himself afloat (though he ‘ain’t’), it was at times unclear whether Lear was saturated by, or impermeable to, the atmosphere in which he moved.

His nonsense rhymes often reflect a comparably unstable approach to place. Poems recording the doings of an ‘Old Man of th’ Abruzzi’ or ‘Young Lady of Norway’ seem to offer geographical specificities as hints at the habits or predilections of Lear’s characters. But the relationship invariably turns out to be arbitrary (which is, as Uglow points out, what makes the limericks funny). Lear was proud of his adaptability and independence as a traveller. He thought of himself as a ‘voluntary exile’, but at other times sought to reassure himself that he had ‘not become so foreignized as before – that is – I hope I am always an Englishman’. Doctors had also suggested that movement might decrease the risk of the epileptic seizures from which Lear suffered. With this in mind, the system by which Lear marked his seizures in his diary begins to look like anguished efforts at self-mapping.

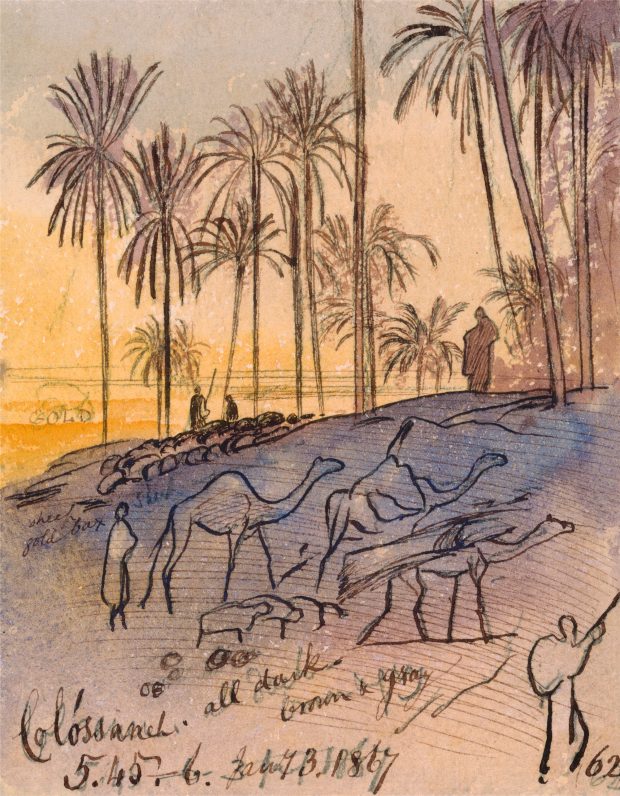

Colósaneh, 5:45–6:00p.m., January 3, 1867 (1867), Edward Lear.

Uglow’s biography tracks Lear’s life in straight chronological fashion. However, she also shows the regularity with which Lear hovered around the same preoccupations, making it possible to read his biography thematically and chronologically at once. His early life takes the form of an astonishing succession of artistic and money-making schemes, a patchwork of education and artistic training – a book on parrots; drawing lessons for Queen Victoria; a sequence of illustrated travel books; a projected set of topographical illustrations for Tennyson’s poetry.

A cedar spread his dark green layers of shade , illustration for Tennyson’s ‘The Gardener’s Daughter’, Mount Lebanon, Syria, (n.d.), Edward Lear. Yale Center for British Art

During his painting lessons with Holman Hunt (‘Daddy’), Lear admired Hunt’s capacity for precision, scrupulousness, and accuracy. Lear also had classificatory habits. One of his earliest commissions as an artist was the catalogues (a ‘great visual filing system’) of the private zoo cobbled together by Lord Derby at Knowsley, to which he contributed bright, sharp watercolours. In preparation for his book of Tennysonian illustrations, he records ‘124 subjects in the 2 volumes’, which he divides into a smaller set of subcategories. His attention to ornithological detail was such that there are now three species named after him: the indigo macaw Anodorhynchus leari, the cockatoo Lapochroa leari, and the red-and-blue parakeet Platycercus leari.

In his Portraites of the inditchenous beestes of New Olland, Lear happily mixes up ‘Ye common Natur Catte’ and ‘Ye Cowe’ with more exotic species. He loved animals that resisted orthodox categorisation, and his poetic humans often seem to be on the verge of transforming into birds or fish. Lear’s crooked knees and long neck, ‘elephantine nose, and […] disposition to tumble here and there owing to being half blind’, make him seem equally on the cusp of metamorphosis. The process works in the opposite direction, too, as the birds in his gorgeous ornithological watercolours are clearly in possession of human qualities. Perhaps the best example of the mixture of shapeshifting and witty improvisation documented by Uglow relates to Lear’s lines about an Old Man who said ‘How, – / Shall I flee from this horrible Cow?’, which were composed more or less on the spot as Lear sat on ‘a dark bovine quadruped’ he had mistaken for a muddy bank.

More poignantly, Lear’s most famous productions – his limericks – can be read as exercises in balancing the strictures of form and the gravitational pull of chaos or accident or depression. Uglow reasonably, if quietly, suggests that Lear’s intense friendships with Hunt, Frank Lushington, and others, and the periods of loneliness in between, are evidence of his homosexuality. At times, Uglow notes, the violence and unruliness of his characters – who cut their own throats or lock each other in boxes – seem refractions or deflections of ‘despair, loneliness, rejected affection’.

The ultimate achievement of Uglow’s account of Lear’s life is that she resists making the comic poems seem like attempts to escape or avoid these questions, as they easily could have been. Instead, she shows how carefully Lear used the limerick form to discover a shape for experiences that were at once resistant to and amenable to shaping – experiences of being clumsy, or mistaken, or mixed up, or more than one thing at once. It’s not only, then, that Uglow takes Lear seriously, but that she shows that, in nonsense, Lear found a way of taking himself seriously.

Mr Lear: A Life of Art and Nonsense by Jenny Uglow is published by Faber & Faber

From the November 2017 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)