Given the unsuitable proposals its management has put forward in recent years, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the Southbank Centre (SBC) is an arts institution suffering from architectural self-loathing. The latest plans have concerned the Royal Festival Hall (RFH), the undisputed jewel in the crown of the South Bank complex. Listed at Grade I 30 years ago, it was the first post-war building to be given that accolade and shares the level of protection afforded to public buildings such as the Banqueting House or the Palace of Westminster. It remains the only physical survivor, and hence is a vivid reminder, of the Festival of Britain, held in 1951 on the South Bank of the Thames.

Few buildings have had such a swift and transformative effect on a city. At the heart of a 27-acre bomb-site, a pale, modernist clear-glazed concert hall rose out of the rubble, to be framed by the Thames when seen across the water. With its welcoming, elegant stairs and its light, bright foyers, wrapped around the ‘egg’ of the auditorium at the core of the building, the RFH seemed the built embodiment of post-war social democratic culture. This aspect of its character was later enhanced by more access to the riverside, enlarged foyer space and, by the early 1980s, a building that was open throughout the day.

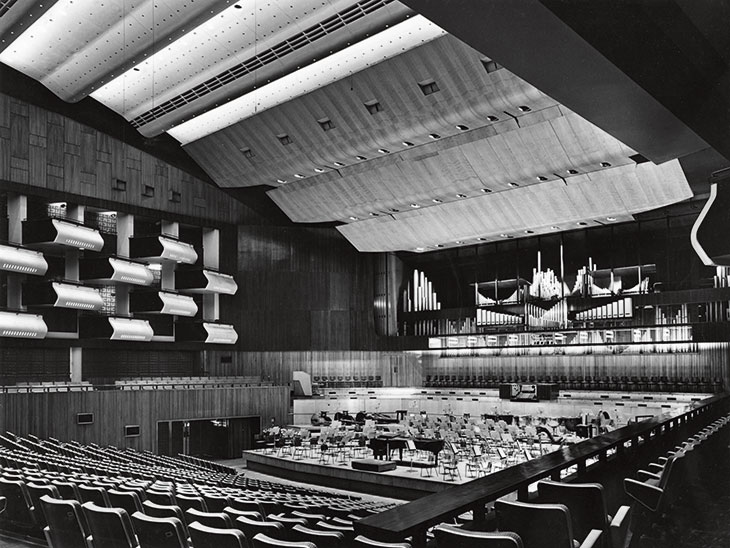

The Royal Festival Hall auditorium, photographed in 1950. Photo: John Pantlin/RIBA Collections

The job of designing and building the new concert hall fell to the London County Council Architects’ Department and Leslie Martin was chosen to head the team. It would take an audience approaching 3,000, compared with the Albert Hall’s 5,000, and had to be complete within three years. The RFH was a prodigious building project for worn-down, post-war London and, as such, ideally positioned to see off every challenge, from the desperate shortage of materials to the lack of women in the building professions (despite their ascendancy in the war years). The professional team was exceptionally young, and the RFH proved a magnet. Jean Symons was an Architectural Association student who opted to work on the Thames-side site rather than lingering in the school design studios, and tenaciously extended her time there from a few weeks to 15 months. Her diary of that experience, a lively mixture of words and images, was submitted towards the AA Diploma she gained in 1951.

The RFH has been refurbished a number of times since, and its ‘dry’ acoustics tweaked to an acceptable standard for all but perfectionists. The most recent works, substantially funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, took place between 2005 and 2007. Allies and Morrison employed great care and sensitivity to reposition the building for the needs of the 21st century. That included making substantial changes to the lower levels, allowing for much greater commercial activity, and additional income for the Southbank Centre. Throughout the process the RFH, under the close outside scrutiny that listed buildings of such importance incur, has kept its essential qualities in equilibrium, finding a subtle balance between gravitas and gaiety.

It therefore came as a shock to find that in September those in charge of the RFH were proposing a pop-up ‘dining and bar venue’ on the roof, to be installed for three years and to be known as the ‘Pergola on the River’. The applicants – the SBC and the Incipio Group (the latter specialists in ‘utilising temporarily vacant and unique spaces’ but who have been criticised for poor detailing at venues elsewhere) – claimed close liaison with the borough of Lambeth, Historic England and the Twentieth Century Society. The latter’s press statement in fact criticised the scheme, which cut across both the roofline and lettering, in the ‘strongest possible terms’ pointing out that their objections at pre-application stage had carried little or no weight.

Listed buildings in public ownership need to pay their way. Thus, in current planning guidance ‘less than substantial harm’ can be considered if it offers a means to bring demonstrable benefits to the building and its users by funding essential works. But this scheme was not proportionate, nor is the SBC fighting a desperate battle to stay solvent. At time of writing, the planning application has just been withdrawn and the Southbank Centre has issued a statement saying ‘The feasibility of the retail proposition […] has proved to be more challenging than anticipated.’

Fairfield Halls in Croydon, designed by Robert Atkinson and Partners in 1962 (photo: c. 1965). Photo: © The Francis Frith Collection

The Royal Festival Hall has been uncommonly fortunate. Compare it with near-contemporary concert halls, notably the slightly smaller Fairfield Halls of 1962, in Croydon, which shared the same supreme acoustic consultant, Hope Bagenal. Unlisted and so precluded from valuable heritage funding, it is currently part of an ambitious regeneration scheme. While the project is running very late and well over budget, the refurbishment of the concert hall seems to be proving the least problematic element of it all. Meanwhile Hans Scharoun’s admired Philharmonie in Berlin, completed in 1963, though badly damaged by fire in 2008, rapidly returned to action, a valued cultural landmark of the first order.

In recent decades there have been more radical plans for the rest of the SBC complex, comprising the Hayward Gallery, Purcell Room and Queen Elizabeth Hall, no part of which is listed, despite the repeated efforts of campaigners. In 1989 Terry Farrell was asked to design substantial alterations to the site, mostly involving the walkways and external stairs, followed a decade later by Richard Rogers whose ‘cool Britannia’ glass roof would have undulated above the brutalist complex.

Since then the management of the Southbank Centre has returned to the fray with more unsuitable and insensitive proposals. In 2013, Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios proposed floating a vast glass cube over the complex. (A pattern seemed to be emerging, although fortunately these ideas went no further.) Then, largely because of the campaign to retain the singular skate park below, FCB carried out a quietly effective upgrading exercise on all three brutalist buildings, funded largely by Arts Council England, and completed by spring 2018. Yet, two months later the Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) handed out another five-year certificate of immunity from listing for the refurbished trio. This inexplicable intransigence in the face of the growing appreciation and evaluation of brutalist architecture is feeding the conspiracy theorists.

The Festival Hall may be safe from irreversible tampering for now, but the recent scheme, coupled with the repeated refusals to seek protection for the rest of the complex, leave significant questions for the SBC management to answer about its lack of regard for the buildings under its care.

From the November 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)