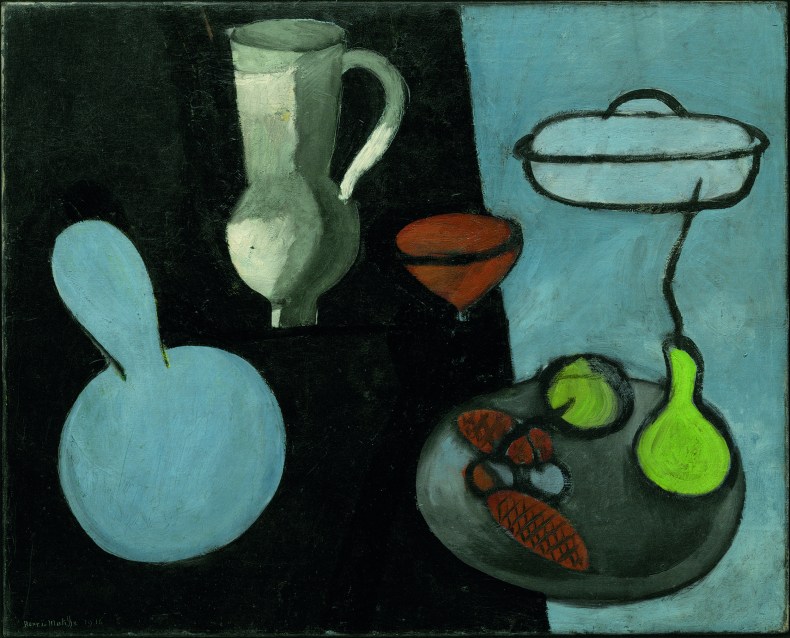

On the right-hand wall, as you enter this exhibition, is a single painting, Gourds, Issy-les-Moulineaux (1915–16). It is merely average in size and its sombre colours convey night-time. A near-vertical division divides the background in two, but neither side offers any secure base for the objects which are left to float in space. Their fixity is at first hard to explain, for there is no obvious formal perfection in their relationships. But above the painting is a description supplied by Matisse’s own words: ‘a composition of objects that do not touch but nonetheless participate in the same intimacy’.

This is the first hint that this exhibition is about the psychology that informs Matisse’s art, and the emotions and intuitions that are bound up with the objects he collected and used in his work. At one level it is a very personal investigation into his obsessions. But it also deepens our understanding of his strenuous, unremitting battle against convention, visual complacency and long-established aesthetic standards. These are increasingly his trademarks as a revolutionary artist. His friends intuited this early on. Partly to tease him, his fellow students used to scrawl on government health warnings posted up in the streets, ‘Matisse is more dangerous than alcohol’, or ‘Matisse has done more harm than war’.

Some of the works in this exhibition have such resolute toughness that they seem to challenge or go beyond the achievement of Picasso. Others affirm Matisse’s ability to entrance. In the first room is Vase of Flowers (1924). Its geometry is immediately striking. Owing to horizontals and verticals – in the open window, the nearby shutter, beneath which is a column of pale blue, in the horizon of sea and the flat tabletop – everything is firmly tied into position. But the main protagonist in this picture is the less tidy shape of the double-handled green-glass Andalusian vase, with its ragged bunch of white flowers. Its abrupt flourish is teasingly echoed by the tiny palm tree outside the window and by the baroque motif in the wallpaper on the far left-hand side, while a faint echo of its exuberance is also found in the dotted patterning in the semi-transparent curtain, half-drawn across the window. This moderates the Mediterranean light and leads on to admiration of Matisse’s deft handling of tone.

Safrano Roses at the Window (1925), Henri Matisse. Photo: © Private collection/© Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2017

This green vase reappears in Safrano Roses at the Window (1925) and in person, in a glass case also displaying two silver-and-wood chocolate pots; the larger and more magnificent one was given to Matisse at the time of his marriage to Amélie Parayre in 1898, by another artist, Albert Marquet. These are significant items within his collection, which moved with him in 1938 when he went south to Nice. There, living at first in the Hôtel Régina, he obtained two glass vitrines in which some of his collection could be displayed, while the rest helped create the intimate environment he needed to sustain his creative continuity and vision. His collection also gave him a ‘palette of objects’ for his drawing and paintings. ‘My purpose,’ he had publicly announced in 1929, ‘is to render my emotion. This state of soul is created by the objects that surround me and cause reactions in me.’

Every time, in this show, an item reappears, it affirms Matisse’s belief that objects behave like actors and can adapt to different settings, playing a new role in each picture. We are told he often moved his objects about to set up new relationships between them. Included here is the collage used to help establish Still Life with Seashell on Black Marble (1940), which went through various stages, as photographs record. In the mutable collage the top and bottom of the tabletop is established by taut strings, while the objects made out of paper cut-outs are simply pinned into position, so that they too can be moved around as the composition demanded.

Matisse’s greatness rests on many things, but the most significant is arguably the way he pushed Western art beyond the boundaries of the European tradition. The main triumph of this show is that it deepens awareness of this. Take the influence on him of African art. He began to collect African carvings in 1906 and by 1908 owned some 20 pieces. This same year he set up his own art school. Max Weber recollected how Matisse would pick up figurines to show his students, pointing out their sculptural qualities, their intuitive sense of proportion and balance. He himself adapted poses from mildly erotic ethnographic magazines, using them as a starting point in his bid for freedom from academic conventions, inspired by the expressiveness and invention of African carvings.

Gourds, Issy-les-Moulineaux (1915–16), Henri Matisse. Photo: © Archives H. Matisse/© Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2017

Equally significant is the Chinese art in Matisse’s collection, notably a calligraphic relief which appears to have encouraged his pursuit of signs in his late work. Roger Fry spotted the Chinese influence in Matisse’s art as early as 1912, but Matisse claimed that his real epiphany in relation to Chinese art came in 1919, in the British Museum in London. ‘A poet showed me all the splendours of the Chinese masters: it was a revelation of a new world for me…I was forced to realise that these Chinese a thousand years ago had already seen our problems and had resolved them more or less in the same way we have today.’ It has been suggested that the ‘poet’ was Matisse’s friend Matthew Stewart Prichard, who had studied Chinese art. But, given that this epiphany took place within the British Museum collections, a more likely candidate for the ‘poet’ in question is surely Laurence Binyon, who had set up within Prints and Drawings a semi-autonomous sub-department for Oriental works, and did much to expand the museum’s Chinese collections. But we are only beginning to uncover the role played by London’s national galleries and their far-reaching collections in the great modernist revolution.

‘Matisse in the Studio’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, from 5 August–12 November.

From the October 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

The threat to Sudan’s cultural heritage