Thomas Schütte is almost too good. The thought occurs to me in the first room of his new exhibition in Venice, where I am immediately faced with three enormous bronze sculptures of giants, surrounded by faded heraldic banners on the walls. It comes to me again while I look at his Egghead series and at the architectural models and luminous glass pieces. It stays with me as I go round the exhibition and even as I leave, with the eyes of the Mother Earth (2024) sculpture in the courtyard boring into me from behind.

The artist’s sculptures exude effortlessness, a feeling helped by the soaring rafters of the Punta della Dogana and its bright, rainbow-shaped windows looking out on to the Grand Canal. The presentation of his work in lots of different rooms allows neat comparisons to be drawn between pieces made decades apart, which makes it seem as though the space – one of two belonging to the Pinault Collection in the city – was specially designed for Schütte.

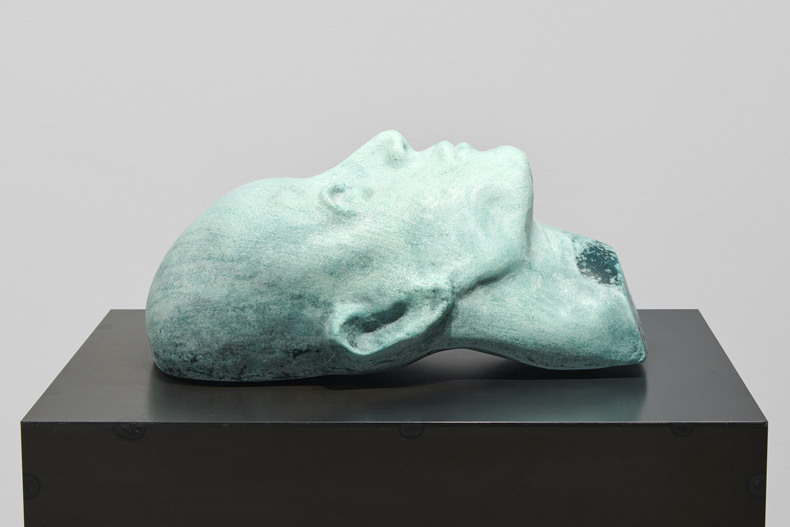

But back to those first sculptures. In Man in the Wind (2018) the patinated bronze of the figures has turned sea-green, with a lighter teal colour pooling on the base around their legs like rock pools. It makes them seem like characters in a fairy tale, an impression reinforced by their childlike facial expressions. Later in the exhibition, there’s a video that shows the artist smacking clay around, squeezing and pressing and pinching faces into ghoulish grimaces. But he’s also interested in simplicity. For Schütte, a face can simply be two eyes and a mouth and, in some cases, a nose too. The whole thing – the symbol of a face, if not a face itself – is assembled on an oval in the Eggheads series. He makes these blank masks expressive with a real economy of gesture: the slice of a potter’s scalpel forms a mouth; a finger pressed through clay marks the imprint of an eyebrow.

Blues Men (2018), Thomas Schütte. Pinault Collection. Photo: Nicholas Knight; courtesy the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc. New York/Paris; © Thomas Schütte, by SIAE 2024

Schütte isn’t just about restraint and he doesn’t confine himself to a single mood. A room that contains his Criminals drawings (1992) and the four busts of Brothers (2012) shows how a motif of guilt (and how visible it may be in someone’s expression) crops up across the years. The show surprises us with switches between caricature and minimalism. The ink and watercolour Blues Men series of 2018 is a perfect example. His portrait of Jimmy Reed is a collection of white paint marks sparsely daubed on black paper, and it’s as evocative and expressive as the detailed grotesques.

The Pinault Collection presents works produced by Schütte mainly in Italy or in collaboration with Italian companies. The Criminali series was made when he was an artist in residence in Rome at the height of the mani pulite (‘clean hands’) political corruption scandal of the 1990s. We also find him working with Murano glass in partnership with the Berengo Studio. Berengo Heads (2011) comprises two hideous goblins cast in diaphanous red and blue glass and positioned by the window to let sunlight stream through their features, which renders their ugliness strangely beautiful.

You 24 (2018), Thomas Schütte. Pinault Collection. Photo: Ben Westoby; courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London; © Thomas Schütte, by SIAE 2024

The show starts to run out of steam near the end. There’s more and more empty space as it goes on; Schütte’s ceramic medallions, for instance, don’t command the rooms as the sculptures do. The watercolours and drawings Schütte made in 2022 from a hospital bed are only passingly interesting. They depict objects from everyday life – a light bulb, a sock, his left hand, an hourglass with a yellow face disintegrating into sand – but there’s no escaping the sense that these were dashed off, sometimes several in one day, out of boredom. The most powerful pieces are more deliberate and tell a story, such as the Geisters (‘spirits’) or Efficiency Men (2005). The former are huge figures that loom over the visitor, uncannily human in their postures but faceless, nightmarish inventions – nothing like the gentle, fairy-tale giants at the beginning of the show. The latter are terrifying metal skeletons on springs wrapped in heavy-duty cloaks with glittering, bulbous, pastel-coloured heads. They look like crows, ready to pick at carrion, slowly advancing or hopping towards the viewer. This is Schütte at his best: creating hulking, humanoid characters that seem to show us ourselves, but are distorted and strange, as though seen in a circus mirror.

‘Thomas Schütte: Genealogies’ is at the Punta della Dogana, Venice, until 23 November.

The surreal films of Jan Švankmajer

The surreal films of Jan Švankmajer

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why it’s time to stop rediscovering Eileen Gray