Funen is a fairy-tale island. It was here, in Odense, that Hans Christian Andersen was born in 1805, which is why the streets of the city are punctuated with bronze statues that depict, among other characters from fable, a girl perched on a flower and a tin soldier with one leg. At the town centre, when I visit in July, is an enormous hole, the size of several football pitches. The hoardings that girdle it show rendered images of a vast enchanted garden, pocked with drum-like structures built of wooden frames – the new Hans Christian Andersen Museum, designed by Kengo Kuma, which is scheduled to open in 2020.

Some 30km south is Egeskov Castle, a picturesque 16th-century water castle that has been embellished in recent years with an adventure playground, a plant nursery and something called ‘Dracula’s Crypt’. Since 2007, when the doll’s house came here on loan from Legoland, its owners since 1978, the castle has also been home to Titania’s Palace. From Copenhagen, I have driven half way across Denmark to look at a doll’s house.

Titania’s Palace installed in the Rigborg Room, Egeskov Castle, Kværndrup. Courtesy Egeskov Castle

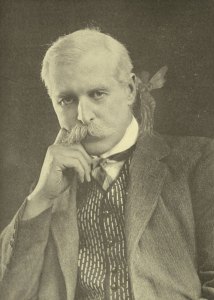

The ‘architect-in-chief’ of Titania’s Palace was Sir Nevile Wilkinson (1869–1940), an artist, army officer and herald who, from 1908 until his death, held the office of Ulster King of Arms. ‘He had something of a giant’s physique,’ wrote the late Conrad Swan in Wilkinson’s ODNB entry, ‘standing 6 feet 5 inches in his stockinged feet and 7 feet 6 inches when wearing his bearskin’ – an ironic stature for a man who would devote so much of his time to the creation and collection of the miniature artworks that he called ‘tinycraft’.

The story that Wilkinson span, in the many publications that accompanied Titania’s Palace as it became a phenomenon in the 1920s, was that, in 1907, his daughter Guendolen had glimpsed a fairy among the roots of a sycamore tree at Mount Merrion House, their home outside Dublin; he subsequently promised to construct – as my illustrated handbook to the doll’s house in an edition from the 1930s has it – ‘a special building […] above ground [so that] The Fairy Queen and her Court might be persuaded to transfer themselves and their treasures to the visible palace.’ Shakespeare, wrote Wilkinson, had ‘made a slight error’ in calling Titania’s consort Oberon: ‘being Irish by birth, he should have been called The O’Beron.’

Cross section of Titania’s Palace, showing the private entrance hall and some of the private quarters

What emerged in July 1922, when Titania’s Palace was officially opened in London by Queen Mary, was a model building that was winningly eclectic in its interiors and contents – and which would only become more so as it acquired further diminutive items during the international tours on which it was dispatched to raise funds for child welfare. Wilkinson had commissioned, in essence, a large neoclassical cabinet from James Hicks of Dublin, nine feet by seven feet and with 16 rooms arranged around a central courtyard. Its single finial, a belfry recalling that of St George’s, Hanover Square, was designed by Edwin Lutyens – whose Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House, the other miniature marvel of the decade, would be completed in 1924. Wilkinson himself painted the interiors in a Renaissance-revival manner, sometimes using a painstaking stippling technique he called ‘mosaic painting’.

‘The Architect-in-Chief and Her Iridescence’ in Titania’s Palace: An Illustrated Handbook

To visit Titania’s Palace – insofar as one can visit a doll’s house – is to be by turns beguiled and bewildered by its amalgamation of purportedly historical objects and tiny replicas varnished with fairy lore. Some 3,000 items populate its private quarters and public halls – the Hall of the Guilds, the Hall of the Fairy Kiss, the Throne Room and a chapel. While Wilkinson often names the makers of miniature furnishings in the handbook – ‘a remarkable sideboard in satin-wood, a masterpiece of Mr. Fred. Early, stands between the windows’ – he sets other objects firmly in the context of fairyland fantasy: ‘the Royal Sleigh, lent at Christmas time to Santa Claus, which accounts for the toy-carrier at the back’. Titania’s Palace teases its onlookers by overlaying narrative possibilities on a type of interior usually considered immobile. A fellow viewer spots Titania’s bicycle propped in the entrance hall: ‘That must be new, that’s not from 1922, is it?’, she asks.

Amid this blend of dreamcraft and dexterity, there are those items that Wilkinson assigns to historical artists or manufacturers: Oberon’s museum contains ‘the finest collections of miniature Bristol glass in the world’, in the Throne Room are ‘two Renaissance figures in solid gold […] attributed to Benvenuto Cellini’, and elsewhere hang paintings given to Claes Molinaer, Samuel Palmer and others. Whatever the veracity of these claims, the experience of peering through glass at these objects – too minute, even at such close distance, to study in any detail – feels like a parable of museum-going, of the faith that we so easily place in official attributions as we wander through a historical collection. As Susan Stewart writes in On Longing (1984), ‘the dollhouse is a materialized secret’.

‘The Hall of the Fairy Kiss’, in Titania’s Palace: An Illustrated Handbook (12th edition; first edition published 1922)

What most entices me here, though, are those human-scaled objects that, transferred into Titania’s Palace, have been transformed into Lilliputian luxuries. At the top of the staircase stands an equestrian statue, ‘the last survivor of a set of Chessmen of Ludwigsburg porcelain dating back to the middle of the 18th century’; against the chapel wall is ‘an Italian casket made of old amber inlaid with marvellously wrought ivory carvings, which once formed the base of a 17th-century crucifix’; and in Titania’s boudoir, there is a folding screen concocted out of ‘Persian playing-cards of the early 17th century’. This is a domestic vision in which nothing goes to waste, in which even orphaned antiques have a place in the magical, miniature order.

From the September 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)