From the September 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Depending on who you ask, Helena Blavatsky was either a mystic and a sage who introduced Eastern spirituality to Western culture, with the stated aim of establishing ‘a universal brotherhood of humanity’, or she was a plagiarist, a racist and a fraud. If you ask me, she was a bit of both. Kurt Vonnegut called her ‘the Founding Mother of the Occult in America’, which is not entirely hyperbole. When she arrived from her native Russia, in 1873, the United States was already in the thrall of new religious movements such as Spiritualism, but it was Blavatsky’s co-founding of the Theosophical Society with fellow seekers Henry Olcott and William Quan Judge that cemented her influence on Western esotericism on both sides of the Atlantic.

Theosophy was popular because it offered an alternative to mainstream institutional religion, which, especially in the Northeastern United States, was increasingly seen to be out of step with progressive social movements and with the ascendency of science and modern industry. It boasted access to an ancient, universal wisdom that predated all the world’s organised religions, a form of knowledge that survived in aspects of Buddhism and Hinduism but which was also compatible with the latest scientific discoveries about the history of the universe.

Madame Blavatsky, as she styled herself, made many extravagant claims, most notably that she had lived in Tibet (then officially closed to Europeans – not to mention remote and inaccessible) where she studied under two gurus named Master Morya and Koot Hoomi, both ‘Adepts’ (as she called them) entrusted with secret ancient knowledge. When she came to write her books Isis Unveiled (1877) and The Secret Doctrine (1888), her teachers telepathically communicated the contents, including references and quotations, translations and all. Blavatsky could allegedly also move objects through telekinesis, could pass things through walls and conjure them from thin air. (She declined, however, to do so in public.) Later in life, a housekeeper accused her of installing secret doors and drawers for such spectacles, but despite this and many other disparagements, most acolytes remained faithful.

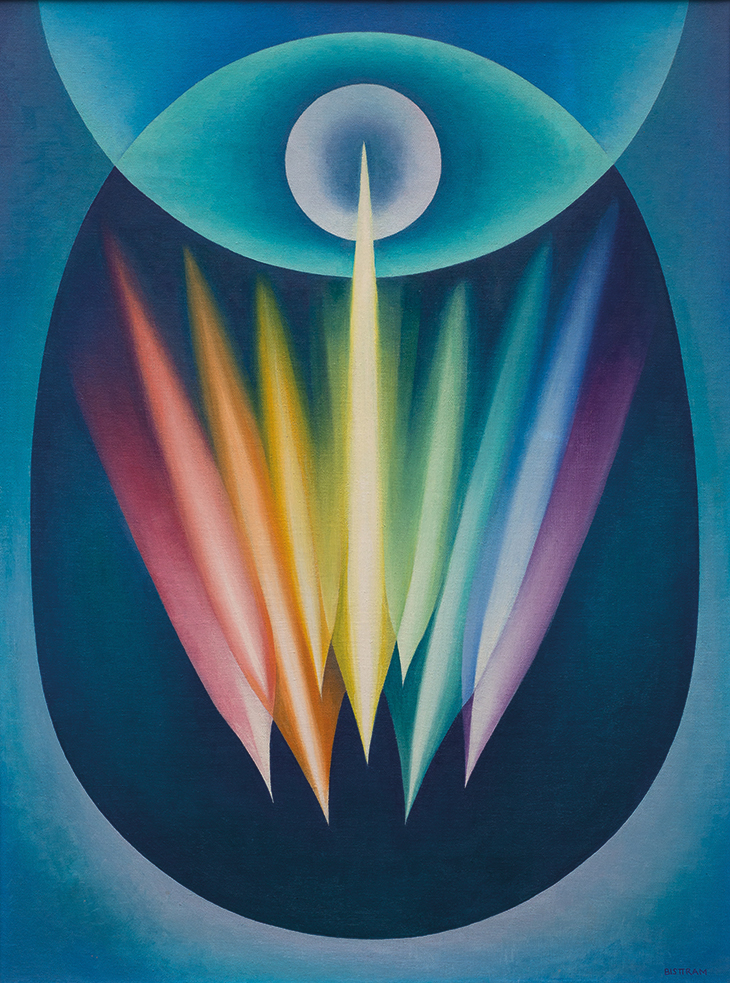

Composition #57/Pattern 29 (1938), Robert Gribboek. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Photo: Geistlight Photography, Albuquerque

What to make of the fact that a significant number of canonical modern artists subscribed to Blavatsky’s Theosophical mysticism or to adjacent esoteric beliefs? Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Frantisek Kupka and Max Beckmann all acknowledged the importance of Blavatsky’s teachings on their work. In Kandinsky’s influential book Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art; 1911), he made numerous references to Theosophy; discussing his essay ‘Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art’ (1917–18), Mondrian wrote, in a letter to Theo van Doesburg, that ‘I got everything from The Secret Doctrine.’

At the time that modernist abstraction was developing apace in Europe, art in the United States was generally mired in social realism, although interest in the European avant-garde was percolating through exhibitions such as the Armory Show of 1913. According to most orthodox histories, it was not until after the Second World War that the baton of the avant-garde was firmly grasped by artists in America.

These standard narratives, however, seem increasingly myopic, thanks in large part to the dogged work of curators such as Michael Duncan, whose long-gestated, five-venue exhibition ‘Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group’ opened at the Albuquerque Museum this summer (until 26 September; the exhibition has been organised by the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento). The Transcendental Painting Group (or the TPG, as it is often called) is, to this day, little known outside of New Mexico, where most of its members worked in the 1930s.

But the TPG’s radical work – inspired, to varying degrees, by Theosophy and esoteric thought – was as experimental and forward-looking as anything on the walls of Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery An American Place, where Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley and Arthur Dove exhibited, or within the membership of Josef Albers’ contemporaneous American Abstract Artists organisation, which included Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. Unlike the abstraction emerging in such circles – which typically built on the analytical cubism of Picasso, Braque, Gris and Léger – the artists of the TPG aspired to use universal symbols and abstract forms to access the transcendent spirit that they believed was in all people, that was manifested in all forms of nature and in the wonders of the cosmos.

Members of the Transcendental Painting Group and friends, photographed in Taos, New Mexico, in November 1938. From left to right: Bess Harris, R.S. Horton, Mayrion Bisttram’s mother, Lawren Harris, Mayrion Bisttram, Robert Gribbroek, Emil Bisttram, Isabel McLaughlin, Raymond Jonson. Courtesy Michael Duncan

Whereas New York modernism was a determinedly Eurocentric discourse, the TPG were aligned with Theosophy’s global outlook – absorbing influences from Hindu and Buddhist aesthetic and spiritual traditions – as well as, to a lesser extent, from the Native American culture that thrived in New Mexico. Simplistic cultural appropriation, however, did not interest them. Ancient wisdom, as touted by Blavatsky, was their path to formal innovation, and, conversely, they believed modernist abstraction could lead to spiritual insight.

As TPG member William Lumpkins (1909–2000) stated in an interview in 1940: ‘Art must keep up with science, that is, creative art must, and as science discovers new angles in life, the creative artist must discover new forms of expression. […] We are not, like the early masters, religious painters, we are scientific painters. We are trying to reach beyond the illusory forms of materialism into the reality of form of the immaterial. We certainly are not trying to formulate a philosophy of life or religion.’

Duncan, who is based in Los Angeles, has been exploring the work of the TPG since he first encountered it in Maurice Tuchman’s landmark exhibition ‘The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985’ at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1986. (Tuchman’s show was also notable for introducing the world to Hilma af Klint, the Swedish Theosophist whose spiritualist, symbolic abstractions from the early 1900s predated many of Kandinsky’s breakthrough paintings.) Given the prescience and importance of Tuchman’s exhibition, Duncan tells me, it is a wonder that for most of the past 35 years the term spiritual has remained largely ‘taboo’ in discussions of both contemporary and historical art. In the catalogue for his exhibition, he develops this point at greater length. ‘While much of the culture-at-large remains dominated by Puritanical Protestantism, critics tend to downplay the presence of spirituality in American art and literature,’ he writes. Consequently, Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau are ‘popularly taken more as crackpot liberals than as spiritual guides to the American psyche’, and ‘the religious convictions of Rothko and Newman have been primarily subsumed into Greenbergian formalism.’

Whether you are sympathetic to the beliefs or preferences of the artists of the Transcendental Painting Group (and they were far from doctrinaire, as we shall see), the rigour of their work ‘mitigates the mumbo jumbo’, as Duncan tells me. ‘The TPG’s works are resolved in a really classic, modernist way.’ Even though, for their makers, they served a ‘higher purpose’, as he puts it, it is hard to deny their technical mastery.

Centrifics (1938), Florence Miller Pierce. Private collection

It is also important, Duncan notes, to draw a distinction between the artists of the TPG and figures such as Hilma af Klint or the Victorian Spiritualist Georgiana Houghton, who believed they were receiving messages and visions from the beyond. ‘The TPG artists are not receiving messages,’ he says. ‘They’re communicating their own spirit.’ As Raymond Jonson (1891–1982), one of the founders of the group, put it, ‘God is in us and not some superior being outside of us. I believe that through the abstract and non-objective we will be able to state at least a portion of what life means.’

The first member of the TPG who really captivated Duncan was also its outlier, but also perhaps its most celebrated figure, particularly after a recent travelling retrospective organised by the Phoenix Art Museum. Agnes Pelton (1881–1961) lived not in New Mexico but in the southern Californian desert, and was older than other members of the group. At the group’s second meeting, in 1938, she was elected in absentia as its honorary president, owing to members’ enthusiasm for her work. She never attended a TPG meeting, but corresponded with its members and became close with some, especially with Dane Rudhyar (1895–1985), the composer, philosopher, painter and writer who was its unofficial spokesman.

Although born in Germany, Pelton grew up in New York, and enjoyed some success as a painter of Symbolist scenes, including female figures in idealised landscapes – ‘interpretations of moods of nature symbolically expressed’, as she described them. In 1913, some were selected by Walt Kuhn for the Armory Show; among her collectors was the heiress Mabel Dodge Luhan. In 1919, Luhan invited Pelton to visit her fledgling literary colony in Taos, New Mexico, where she was building a pueblo-style adobe mansion on 12 acres of land. Pelton was deeply affected by the landscape in New Mexico, as well as by the Native American culture that she encountered in the region.

It was not until more than a decade later, in 1931, that Pelton made the permanent move from the East Coast to the Southwestern desert, settling in Cathedral City, then a small, sparse town near Palm Springs. In her remote home, Pelton pursued her practice of Agni Yoga, and read widely, including texts on Theosophy, Rudolf Steiner, Krishnamurti and tantra. The unique qualities of light and space in the desert made an indelible and unmistakable impact on her paintings, both the conventional landscapes that she sold to earn a living and the hallucinatory abstractions that often seem to describe ethereal apparitions rising in twilit skies.

Alchemy (1937–39), Agnes Pelton. The Buck Collection at the UCI Institute and Museum of California Art

‘Light is the keynote of these pictures,’ she wrote, soon after her move. ‘Not as it plays on objects in the natural world, but through the space and forms, seen on the inner field of vision.’ This emphasis on interiority was what set Pelton and the TPG apart from most modern abstract painters of the period, including Georgia O’Keeffe, with whom Pelton is often compared. While others were concerned primarily with external visuality, and what Rudhyar termed ‘the intellectual abstract’, the TPG aimed to represent something much more profound and ineffable: ‘the wonders of a richer and deeper land – the world of peace – love and human relations projected through pure form,’ as Raymond Jonson wrote in 1937.

Along with Emil Bisttram (1895–1976), who lived 70 miles north in Taos, Santa Fe-based Jonson spearheaded the organisation of the group. Jonson was an energetic promotor of his own and his peers’ artwork. He taught at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, and also sold art supplies from his studio, activities that put him in touch with a broad network of the region’s artists.

Like Pelton’s, Jonson’s early explorations were in Symbolism, but his work became increasingly non-representational after he moved to New Mexico from Chicago in 1924. While Jonson was drawn to a range of spiritual thinkers, including the philosopher-painter Nicholas Roerich (an influence on many in the group, including Bisttram and Pelton), he was not a strict follower of Theosophy nor any other religious school or sect. It was reading Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art that made the deepest impact on him, and catalysed his pursuit of abstraction. His paintings from the 1930s are characterised by their dynamic graphic style; sharp-edged areas of gradated colour meet and overlap, as if in translucent layers. While most paintings are entirely abstract, they are often composed around glowing discs, which inevitably evoke natural landscapes beneath the sun or moon. Jonson’s purchase in 1938 of an airbrush enabled him to achieve such luminous effects even more perfectly. He shared with Pelton, and with most members of the TPG, a palette based in pastel colours, particularly mauves, pinks, apricots and powder blues – the evanescent shades of the sky at dawn and dusk.

Creative Forces (1936), Emil Bisttram. Private collection Courtesy Aaron Payne Fine Arts, Santa Fe

Bisttram was also a natural teacher, first at Roerich’s Master Institute of United Arts in New York, and later at the Taos School of Art, which he himself founded in 1932. His roots were in commercial art: until the economic crash of 1929, he had led a successful company that created artwork for advertising. Meanwhile, he became fascinated by a compositional theory called Dynamic Symmetry, based on the geometry of ancient Egyptian, Islamic and classical art. This led him to the teachings of Roerich, of Emmanuel Swedenborg, of P.D. Ouspensky and of Blavatsky. While he was sympathetic to such arcane and esoteric sources, Bisttram was something of a rationalist who strived to establish aesthetic formulas and processes that he could replicate in his art. Like so many of these spiritual questers, Bisttram wanted to correlate a modern scientific approach to the world with ancient knowledge. He reportedly abhorred emotionalism, instead setting store by his studies of mathematics and a strict lifestyle of yoga, astrology, vegetarianism and sexual abstinence.

Three others of the TPG were students and acolytes of Bisttram: Florence Miller Pierce (1918–2007); her husband, Horace Pierce (1916–58); and Robert Gribbroek (1906–71). While all were familiar with Blavatsky’s writings, the only official Theosophist in the TPG was the acclaimed Canadian landscape painter Lawren Harris (1885–1970), who had fortuitously relocated to Santa Fe in 1938, just as the group was taking shape. Jonson, who had been deeply impressed by an earlier exhibition of Harris’s work at the Nicholas Roerich Museum in New York, introduced himself when he happened to spot Harris and his wife walking past his Santa Fe home studio. They became close friends, and the fervour for non-representational painting that Harris discovered among this group of artists undoubtedly enabled his work to turn a corner away from the essentialised regional landscapes for which he was celebrated in Canada to more imaginative, universalised abstractions – still based in landscape – that he made during his time in New Mexico. Unfortunately, in 1940, Canadian wartime regulations prohibited the transfer of Canadian currency out of the country, and Harris was forced to return to his homeland.

At their first meeting, in 1938, the group debated at length what it should call itself. While superficially accurate, the terms ‘abstract’ and ‘non-objective’ were already overused and wedded to a certain European discourse that was latterly being institutionalised by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Transcendentalism was an American tradition established a century earlier, but was also not quite right. Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman and their peers believed that God was in nature and nature was God’s earthly manifestation; instead of nature, the artists of the TPG aimed for a dialectic between the inner self and the spiritual (even if natural forms were often the context for this communion). They settled, with the approval of Pelton, on ‘transcendental’ rather than Transcendentalist.

Abstract Painting No. 95 (1939), Lawren Harris. Collection of Georgia and Michael de Havenon

The TPG adopted the trappings of an official organisation: it had a chairman (Jonson), a treasurer (Lumpkins), a logo (a geometric abstraction of a butterfly) and even a printed leaflet stating its membership, beliefs and intentions. What did it hope to achieve with such formalities? One goal that its members worked especially hard to achieve was an exhibition at Hilla Rebay’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting in New York (later renamed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum). This they accomplished – more or less – when six of the group were featured in a show titled ‘12 American Non-Objective Painters’ in 1940. With the paintings hung separately, however, it was not quite the triumphal acknowledgment of their radical new movement that they had hoped for.

In 1939, the TPG had also exhibited together at the World’s Fair in New York, and over the following years they showed work in several regional galleries in New Mexico and California. But as the Second World War exerted its centripetal force on structures and communications on both sides of the Atlantic, the group disintegrated.

Why did these artists never receive the recognition that they sought, and which – in retrospect – it seems obvious they deserved? Duncan points, in part, to the misfortune of hailing from ‘the wrong side of the Mississippi’, especially at a time when New York was in the ascendant as a global art capital. Georgia O’Keeffe, who was very successful during her lifetime and who is, today, probably the artist most immediately associated with New Mexico, seems to have been almost completely indifferent to their work. Duncan conjectures that this reflects O’Keeffe’s alignment with New York, where her husband Alfred Stieglitz remained her most influential champion.

The impact of the Second World War should also not be underestimated. While the TPG saw their agenda as an alternative – the only alternative – to materialism, mechanisation and, ultimately, to Fascism, the American public likely had little time for cosmic vibrations and sacred geometry as the exigencies of global conflict drew closer to home. The TPG’s geographic removal from the cultural frontlines, a fact that had facilitated the group’s emergence and shaped its identity, finally contributed to its undoing.

Mentions of spirituality, in 1940 or throughout most of the ensuing decades, may have caused most art critics and historians to – consciously or unconsciously – consign the artists of the Transcendental Painting Group to a broad category of cranks and crackpots, outsiders and eccentric visionaries. But that finally seems to be changing. If there is a general sense that mainstream Western modernism did not lead us anywhere good (or, at least, anywhere as good as it had promised), then perhaps there were other moments of possibility, paths not taken, that might have contributed to a very different cultural present. Perhaps it is time to walk down them.

‘Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group’, organised by the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, is at the Philbrook Museum of Art until February 20, 2022 (then touring).

From the September 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)