If there is a central purpose that guides the eclectic work of Trevor Paglen, it is perhaps the desire to create art that, as he said during a recent lecture, ‘gives us a tiny glimpse of how the rules of the world might be different’. In ‘Sites Unseen’, an expansive survey that recently opened at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., we see the fruits of this pursuit, from the photographs of surveillance sites and reconnaissance satellites that established Paglen’s reputation in the mid 2000s to more recent forays into sculpture and mixed media. For Paglen, who has a PhD in geography from the University of California, Berkeley, the rules of the world are always mediated by perception. As an artist – he rejects the term ‘activist’ to describe his work – he is invested in deconstructing, contextualising, and rematerialising the often invisible networks and infrastructures that govern our lives.

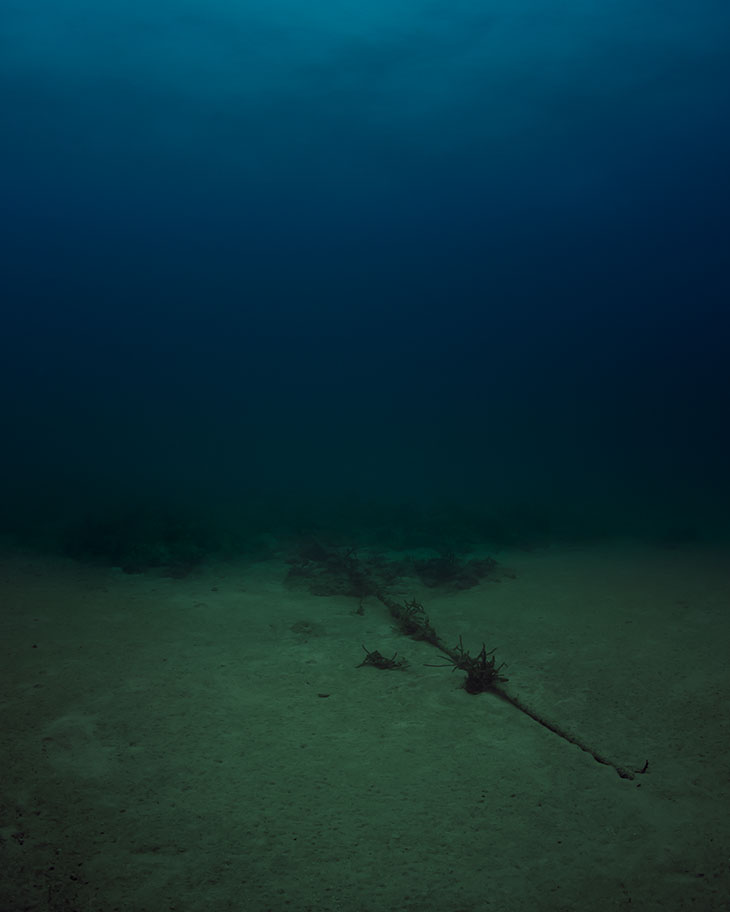

Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1) NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable Atlantic Ocean (2015), Trevor Paglen. Photo: Trevor Paglen; courtesy the artist, Metro Pictures, New York and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco; © Trevor Paglen

Take, for instance, his photographic series Undersea Cables. Aided by classified files leaked by Edward Snowden in 2013, Paglen learned to scuba-dive, determined the locations of underwater internet pipes, and photographed them. The murky blue-green large-scale photos of submerged cables seem fairly quotidian until one realises that Paglen has located points where, in essence, what we once called the World Wide Web is made material. This web is also, of course, the central vehicle through which surveillance is conducted. A related series, Cable Landing Sites, consists of diptychs that show, on one half, shores where cables converge and can be easily tapped, and on the other, nautical charts and collages of documents related to these cables.

NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, Keawaula, Hawaii, United States (2016), Trevor Paglen. Photo: Trevor Paglen; courtesy the artist, Metro Pictures, New York and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco; © Trevor Paglen

While the political message of these images seems clear – ‘[w]e’re always being watched,’ Paglen once told a reporter for the New York Times – the beauty of the photographs punctures paranoiac readings. His untitled photographs of drones, for example, juxtapose the unnatural machinery with the natural technicolour interactions of light and cloud in the earth’s atmosphere. Drones become mere specks dwarfed by sky. In the exhibition, curator John Jacob frames these photographs as a contemporary take on the American landscape photography tradition exemplified by Timothy O’Sullivan in the 19th century and Ansel Adams in the 20th. A photograph by O’Sullivan of Shoshone Falls in Idaho, taken in 1874 while O’Sullivan was serving as official photographer for a US government land survey, is juxtaposed with Paglen’s photograph of the same spot in 2017. Paglen’s image, however, is overlaid with lines that demarcate what two computer artificial intelligence algorithms ‘found’ in the picture. One algorithm, for instance, found shapes in the waterfall it thought were human faces; another sought out underlying lines. Works like Shoshone Falls, Hough Transform; Haar (2017) are representative of Paglen’s recent turn to imagining what he calls an ‘alternative visual culture’ that asks what the world looks like from the perspective of artificial sensing systems. By shifting perspective in this way, Paglen’s newest works suggest a rich field of inquiry for the artist’s evolving investigation of invisibility and perception.

Shoshone Falls, Hough Transform; Haar (2017), Trevor Paglen. Photo: Trevor Paglen; courtesy the artist, Metro Pictures, New York and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco; © Trevor Paglen

Surely no other city in the United States so fully embodies the geographies that ‘Sites Unseen’ documents like Washington, D.C., a city filled with the secret places and missions and people that obsess Paglen. Part of the point of Paglen’s work is that what seems impossible to see (‘secret’ government satellites, NSA office buildings) are in fact perfectly visible if you only know where to look. No one knows this more than the millions of Washington government workers who labour in these mysterious jobs every day, and in this sense, the exhibition and the city are perfectly matched. Yet both Washingtonians and others might wonder about the ultimate purpose of Paglen’s exposure of hidden places: is he attempting to educate the public? To provoke outrage?

A potential answer may be found in Paglen’s most ambitious project yet, which is represented by a scale model in the exhibition. This October, in collaboration with the Nevada Museum of Art, Paglen will launch Orbital Reflector, a satellite that will have ‘no commercial, military, or scientific purpose’. The diamond-shaped balloon, the first sculpture to be launched into space, will simply reflect the sun’s light back to earth. For Paglen, the piece’s ‘uselessness’ is precisely what makes it powerful, fulfilling his desire to imagine an aesthetics of the beautiful in an artificial age.

‘Trevor Paglen: Sites Unseen’ is at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., until 6 January 2019.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)