From the September 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Sometime in the mid 1990s, I was standing in the marble courtyard of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus when two nuns asked me where they could find the head of John the Baptist. I pointed them towards the grand transept facade, gleaming with green and gold mosaics evoking a fertile paradise. Beyond lay the shrine to John or Yahya ibn Zakariyya, as he is known in Arabic, one of the few shared sites of Muslim-Christian pilgrimage. In 2001, Pope John Paul II would pray there – the first time a pontiff had ever visited a mosque.

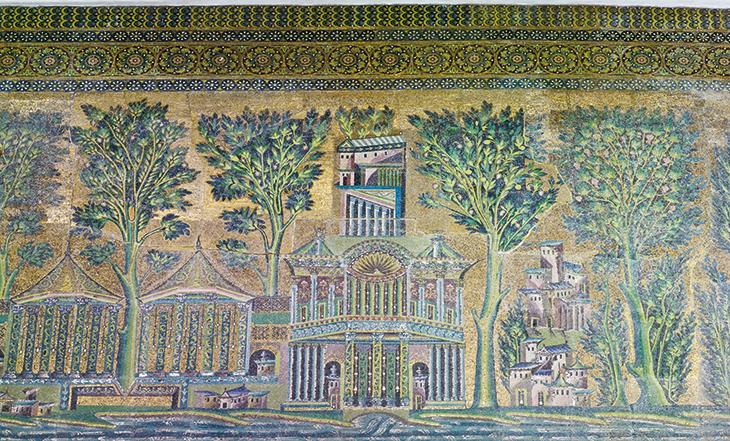

Detail of the river mosaic on the west courtyard wall. Bernard O’Kane/Alamy 2007

Alain George’s illuminating new study shows us that the Umayyad Mosque has always been claimed by rival faiths. George, born in Beirut and now professor of Islamic art and architecture at Oxford, writes that the mosque ‘is one of the oldest continuously used cultic sites in the world’. In the first century, the Romans built a temple to Jupiter, whose columns shoppers in the Old City’s Souq Al-Hamidiyah still amble past today. The place was Christianised in the fourth century; after the Muslim conquest in the 630s, a mosque was built within the walls, and for a few decades it remained in uneasy co-existence with the church.

After taking power in 705, the Umayyad caliph al-Walid, keen to match his father Abdul Malik’s magnificent Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, ordered the creation of a palatial court-mosque in his capital Damascus. But first he needed to clear out the church. After his offer to buy it was rejected, he ordered his Christian workmen to destroy it. When they refused, the caliph, dressed in a yellow robe, struck the first blow with a pick-axe. The mosque took 10 years to complete and cost the equivalent of a full year’s tax revenue raised from Basra.

Arcade leading to the Umayyad Mosque, through what remains of a Roman temple to Jupiter. Photo: Alain George (2010)

Al-Walid’s panegyrists also got to work. When the church and mosque were side by side, ‘people of the book would pray, / the chanting bishops echoed back […] like swallows chattering at dawn.’ But now, ‘prayer of holy truth holds sway / and God’s authentic word is known.’ Still, according to Islamic protocol you weren’t actually allowed to destroy churches. The Byzantine emperor Justinian II reminded al-Walid that Abdul Malik had protected the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The caliph said he would destroy that church as well unless Justinian sent 200 of Constantinople’s best workmen to Damascus. The weak emperor grudgingly complied.

Who actually built the mosque? The Aphrodito Papyri archive in Egypt contains documents relating to the project, including ‘requests for workers, maintenance stipends and, in one case, 47 litrae (about 15–20kg) of chains’. One Enoch, son of Victor, is listed as a middleman. There are no accounts of work on the Damascus mosque itself but you can get a flavour from reports on the rebuilding of the Prophet Muhammad’s mosque in Medina, which took place around the same time. One fed-up worker scrawled a pig on the apex of an arch. (He was beheaded.) An even more foolhardy soul tried to urinate on the Prophet’s tomb before, as the Muslim chronicler relates, being miraculously struck dead. While at the Damascus mosque there are painted red animals on an arch, they don’t look like pigs and are more likely to be graffiti from Roman times. A Greek biblical inscription does remain legible on the lintel of the triple gate – perhaps a sneaky act of subversion by Christian builders.

Where, in all this, does John the Baptist fit in? Damascus is more usually associated with Saint Paul and there is no mention of the Baptist’s shrine before the Muslim era. Most likely, argues George, the Umayyads simply reassigned a skull-relic to John. ‘By anchoring the mosque deeper in its Christian past,’ he writes, ‘they bestowed on it a sacred aura that the church itself had lacked.’

Transept facade of the Umayyad Mosque, Damascus (photo: Alain George, 2010)

This is certainly plausible. But I wonder if George hasn’t missed another element. During this era Shias were forging an identity in opposition to the Sunni Umayyads. After Imam Hussein was killed in 680, his head was taken to Damascus for display. There is a shrine in this spot still visited by Shia pilgrims – I was one of them back in the 1990s. As Stephennie Mulder points out in The Shrines of the ‘Alids in Medieval Syria (2014), there are reports that Hussein’s head was kept in the same place as John the Baptist’s. Could the Umayyads have buried the potentially rabble-rousing story of Hussein’s martyrdom by melding it with the tale of another beheaded martyr, but one whose story was safely told in the Qur’an?

I have focused here on the stories around the mosque rather than George’s impressive though sometimes rather technical descriptions of its architectural features. He is very good on the many transformations the mosque has undergone over the years, especially after being afflicted by invasions, wars and multiple fires. (In 1893, the roof and much else were destroyed after a workman sparked up his hookah.) Some of the period pictures of the mosque being repaired are splendidly evocative – particularly one of fez-wearing painters in the 1920s copying the famous mosaics.

But the tangled nature of the mosque’s religious history exerts an irresistible pull. Over the last 10 years, Syria’s civil war has ripped its communities apart with Christians, Sunnis and Shias all targeted for their religion. And while the mosque hardly has a cosy interfaith past, it is also true that each group feels a special connection with the place. During one 15th-century fire, an eyewitness named Ibn al-Himsi reported: ‘The marble burned down and collapsed like melting salt. Glass bits fell alongside a grilled glass window and the lead from the roof melted down […] All grieved profoundly; even the Christians and Jews wept at the sight, as did the people who flocked in from the villages.’

The Umayyad Mosque of Damascus: Art, Faith and Empire in Early Islam by Alain George is published by Gingko.

From the September 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)