Vincent van Gogh was at the height of his powers in Arles, painting with intense colours under the strong sun of Provence. Paul Gauguin later joined him at the Yellow House, but tragically this collaboration was brought to an end by Van Gogh’s self-mutilation – an incident that has sparked endless speculation. Why did Van Gogh cut off his ear and take it to a brothel? Behind this sensationalist query lies a more serious conundrum. What led such a creative artist to become so destructive? As Claude Monet put it, ‘How could a man who has loved flowers and light so much and has rendered them so well, how could he have managed to be so unhappy?’ [1]

Nearly a century after Monet’s comment, interest in Van Gogh’s 444 days in Arles only grows. In the past few months there has been a spate of publications: Bernadette Murphy’s Van Gogh’s Ear: The True Story (Chatto & Windus), my own Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln), and Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov’s Vincent van Gogh: The Lost Arles Sketchbook (Abrams). The Van Gogh Museum has also tackled the artist’s medical problems this year in an exhibition, ‘On the Verge of Insanity’ (15 July–25 September). [2]

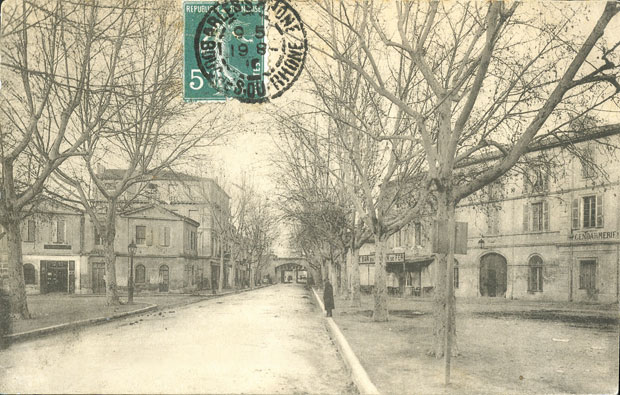

The Yellow House (left) and avenue de Montmajour, Arles, in a postcard of c. 1905. Image courtesy the author

But there is always more to discover, even about such a famous artist and much studied events. As my book was going to press, I discovered a 1933 article in a Dutch newspaper, which has escaped the attention of specialists. This includes the revelation that Van Gogh was ‘arrested’ over the ear incident. [3] The claim in De Groene Amsterdammer might be dismissed as a sensationalist embellishment, but it was based on an interview with Alphonse Robert, the policeman who had gone to the brothel and went on to become chief warden at the municipal jail. The article was written by Benno Stokvis, one of the best informed early Van Gogh scholars, who was also a distinguished lawyer. Both men would have been well aware of the legal meaning of the word ‘arrest’.

In De Groene Amsterdammer, Robert recalls being on duty in what Van Gogh called ‘the street of the kind girls’, the rue du Bout d’Arles. [4] A prostitute summoned him to see her patronne, Madame Virginie Chabaud, who told him: ‘Look, Monsieur Gogh who just departed from here, left this for that girl’. Inside the gruesome packet was a severed ear. Robert took it to his superior, who ordered two other policemen to help search for Van Gogh. They found him on his bed. Stokvis recounts: ‘Robert’s colleagues shortly afterwards arrested Vincent, and the doctor from the hospital, who had been warned in the meantime, had the painter transported to the Hospices Civils de la Ville d’Arles.’

The intriguing question is why was Van Gogh arrested? We can only speculate, but the police may well have regarded him as a threat to others, perhaps following a complaint from Gauguin. In his memoirs, Gauguin wrote that Van Gogh had threatened him with a razor near the Yellow House, although this claim has often been dismissed by those who feel that Gauguin was trying to evade responsibility for what occurred. Gauguin then added that he had escaped to ‘a good hotel’. A long-forgotten reference in a 1928 German magazine records this as the Hotel Thévot, in rue du Forum, very close to the café terrace which Van Gogh had painted in the Place du Forum. [5]

The Place du Forum, Arles, showing the Hotel Thévot in a postcard of c. 1905. Image courtesy the author

This year the young woman in the brothel who received the ear has been identified. The strength of Murphy’s book is her research into the people in Van Gogh’s milieu in Arles. She laboriously built up a database of the people, tracing the family and business relations of Van Gogh’s neighbours around Place Lamartine. [6] Murphy says that she worked out the identity of the young woman in the brothel, but had promised her descendants that she would never reveal the surname. Based on clues in Van Gogh’s Ear, I named her as Gabrielle Berlatier. [7] It is now possible to add further details. On 15 October 1890, nearly two years after the ear incident, Gabrielle married Jacques Achard, a butcher, and they settled in the village of Pont de Crau, two kilometres south-east of Arles. Their daughter Marthe was born nine months after their wedding.

But who was Gabrielle? Murphy says that she was not a prostitute, but a maid. She was only 19, and prostitutes in legal premises had to be 21, although this law was not always observed. [8] Whatever her status, Gabrielle was at the brothel at 11.30pm when Van Gogh appeared, and in the late evenings some of the inebriated customers may well have thought that she was available.

In searching for the trigger for the self-mutilation, most writers have put the blame on Gauguin, who had threatened to leave Arles after relations with Van Gogh became strained. But I believe that the immediate cause was fear of abandonment from another quarter – by Vincent’s brother Theo, who had become engaged to Johanna (Jo) Bonger after a whirlwind romance. Vincent is known to have received a letter from Theo that arrived in the morning of Sunday 23 December 1888. [9] Based on an analysis of family correspondence, I am convinced that this letter, now lost, included news of the engagement. Around 12 hours after its arrival Vincent mutilated himself.

What has escaped the attention of Van Gogh scholars is that Theo’s fiancée Jo received a telegram of congratulations on 23 December from her older brother Henry (this is mentioned in an unpublished letter from Theo to his sister Lies). [10] It is very likely that Theo and Jo would have informed both elder brothers on the same day, which adds to the evidence that news of the engagement reached Arles on 23 December. The envelope of a letter from Theo, quite possibly the one about the engagement, appears in Still Life with Onions and Letter, painted a month later.

Vincent feared that Theo’s marriage would mean that he would lose the financial and emotional support of his brother. Vincent, who could not sell his paintings, was able to survive as an artist only because of the regular allowance he received from his brother. Marriage was likely to lead to children, and Theo would have considerably less money available. The two brothers were also very close to each other, and Vincent worried that he would lose his brother’s affection. Fear of abandonment was the probable trigger for the mutilation.

Van Gogh’s underlying medical and psychological condition still baffles specialists. A symposium at the Van Gogh Museum on 14–15 September assembled experts to discuss a diagnosis, but even this gathering of specialists proved unable to reach a clear consensus. Interestingly, one of the conditions proposed, borderline personality disorder, is characterised by a fear of abandonment. [11]

Separating Van Gogh’s life from his art is difficult; both are so closely intertwined. But it is the art which has the lasting importance and is the primary focus of my new book, Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence. Coming from the Netherlands and Paris, Van Gogh was immediately struck by the strong light of Provence – the powerful sun and vibrant colours. Living in the Yellow House just outside the ramparts of Arles, he was only a few minutes’ walk from the countryside. It was in Provence that Van Gogh really became a landscape artist. For the first time, he described himself as such, rather than simply calling himself an artist. Four months after his arrival in the town, he first used the term, and when he was hospitalised after the ear incident he formally gave this as his profession for registration as a patient. [12]

Van Gogh set out to capture the blossoming fruit trees, the golden tones of the wheatfields, the waterways and their bridges, the hills of the Alpilles with the ruined abbey of Montmajour, and seascapes at Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. The Yellow House was his home and base, but the surrounding countryside became his ‘studio’, as he worked outside. Despite the fact that Van Gogh’s medical problems rendered him unable to work for some of his final months in Arles, he completed around 200 paintings there – an average of more than three a week. Half of these were landscapes.

While in Arles, Van Gogh was on the verge of winning recognition. He had given one of his finest orchard scenes to his cousin Jet, the widow of the artist Anton Mauve. In Jet’s house, Pink Peach Trees was spotted by Jozef Israëls, the most distinguished Dutch painter of the time. On seeing the picture, the elderly Israëls commented that Van Gogh was ‘a clever lad!’ This astonishing comment was passed on in a letter to Theo on 23 December 1888. [13] Had Vincent heard this accolade from an artist he had long admired, would he still have picked up the razor?

The Harvest (1888), Vincent van Gogh. Courtesy Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

The latest of the Van Gogh publications is Vincent van Gogh: The Lost Arles Sketchbook, due to be launched at an international press conference in Paris on 15 November (just after Apollo had gone to press). The book reproduces 65 newly revealed drawings, which are presented as pages from a sketchbook that Van Gogh used from May 1888, soon after his arrival in Arles, up until shortly before he left the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in May 1890. It is being published by two well established specialists – its author, Welsh-Ovcharov, and Ronald Pickvance, who has provided the foreword. Welsh-Ovcharov says that Van Gogh gave the sketchbook to Dr Félix Rey in Saint-Rémy in May 1890 (a visit unrecorded in Vincent’s letters). Rey then delivered it a few days later to his friend Marie Ginoux, who ran the Café de la Gare in Arles. On Marie’s death in 1911 the sketchbook passed to her niece Marguerite Crevoulin, who died in 1927. Crevoulin’s ownership is undocumented and the book does not name the owners since then.

In 1944 the sketchbook (along with a small notebook used to record the running of the Café de la Gare in 1890) was found in a partially bombed building near the Yellow House. The unnamed woman then gave the sketchbook to her daughter for her 20th birthday in 1964 (suggesting that the current owner is now aged 72). Neither the late mother nor her daughter apparently guessed the drawings might be by Van Gogh until recently, although they are both said to have frequently visited the Yellow House at a time when the artist had long become famous. Three of the sketches actually depict the Yellow House (with views similar to that of Van Gogh’s well known painting), so it is surprising that the two women never guessed who might have made them. There may be a firm provenance stretching back to Marie Ginoux, but further details would be helpful.

Welsh-Ovcharov describes the unsigned sketches as for ‘Van Gogh’s eyes only’. They were ‘rapidly executed “first drafts” of motifs observed in situ, meant to be kept and reworked at a later date, or explored as a first idea for a painting’. [14] It therefore has to be asked why Van Gogh gave away two years of preparatory work to Marie Ginoux. On the basis of reproductions, the drawings seem somewhat crude in style and technique. It is unfortunate that the sketchbook and accompanying notebook were both disbound in recent years.

Genuine Van Gogh discoveries are rare – with perhaps one drawing or painting being authenticated every decade. Here we have 65 drawings, so Pickvance describes it as ‘the most revolutionary discovery in the entire history of Van Gogh’s oeuvre’. If the sketchbook is accepted as authentic, then specialists will need to rethink Van Gogh’s creative process in Provence. The sketches were apparently not submitted for a full examination at the Van Gogh Museum, which has the best group of specialists, an extensive archive, and the appropriate scientific equipment. In particular, the ink (and its fading) needs further analysis. Although not infallible, the museum is the best judge of authenticity. In the meantime, caution would be advisable.

Martin Bailey, who completed his article immediately before publication of the Lost Sketchbook, now comments: ‘Having studied the available evidence, I do not believe the drawings are authentic’.

After publication, the Van Gogh Museum issued a statement dismissing the sketches as ‘imitations’ of the artist’s work.

Seuil, the French publisher of the Lost Sketchbook, responded with a counter-statement on behalf of its author, Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, arguing that the drawings are authentic.

[1] Léon Daudet, Écrivains et artistes, Paris, 1927, vol. 1, p. 154.

[2] I also published a detailed account of the ear incident in ‘Drama at Arles: New Light on Van Gogh’s Self-mutilation’, Apollo, vol. CLXII, no. 523 (September 2005), pp. 30–41.

[3] De Groene Amsterdammer, 30 December 1933, p. 8. The Dutch article uses the word ‘arresteerden’, presumably a translation of the French ‘arrêté’.

[4] Letter from Vincent to Theo van Gogh, 18 September 1888 (this translation is from the 1958 edition of the letters).

[5] The archival records of arrests in Arles do not record Gauguin or Van Gogh, but the surviving documents may be incomplete. For Gauguin’s memoirs, see Mercure de France, October 1903, p. 130. For the Thévot reference (based on information from Dr Félix Rey), see Max Braumann, Kunst und Künstler, vol. XXVI (September 1928), p. 453 (my thanks to Teio Meedendorp, of the Van Gogh Museum, for this reference).

[6] For instance, Murphy identifies Van Gogh’s cleaning lady as Thérèse Balmossière (p. 94) and suggests names for two of his portrait sitters (Thérèse Catherine Mistral as ‘the Mousmé’ [p. 96] and François Casimir Escalier as ‘the Peasant’ [p. 98]).

[7] The Art Newspaper, September 2016. The key evidence was in the archive of the Institut Pasteur in Paris, where there is a record of Berlatier’s treatment for rabies in January 1888.

[8] A few months before the ear incident a ‘patronne’ in rue du Bout d’Arles employed underage prostitutes (Le Forum Républicain, 22 April 1888).

[9] The letter which arrived on 23 December 1888 is mentioned in Vincent’s letter to Theo, 17 January 1889.

[10] The telegram is referred to in Theo’s letter to Lies, 24 December 1888 (Van Gogh Museum archive, b918).

[11] Nienke Bakker, Louis van Tilborgh and Laura Prins, On the Verge of Insanity: Van Gogh and his Illness, exh. cat., Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, 2016, p. 125. Van Gogh may not have suffered from borderline personality disorder, but it is a possible diagnosis.

[12] Letter from Vincent to Wilhelmina (Wil) van Gogh, 16–20 June 1888; hospital registration quoted in Alfred Massebieu, Mercure de France, 1 December 1946, p. 232.

[13] Letter from Wil to Theo and Jo, 23 December 1888 (Van Gogh Museum archive, b2387).

[14] Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, Vincent van Gogh: The Lost Arles Sketchbook, New York, 2016, p. 57.

From the December issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)