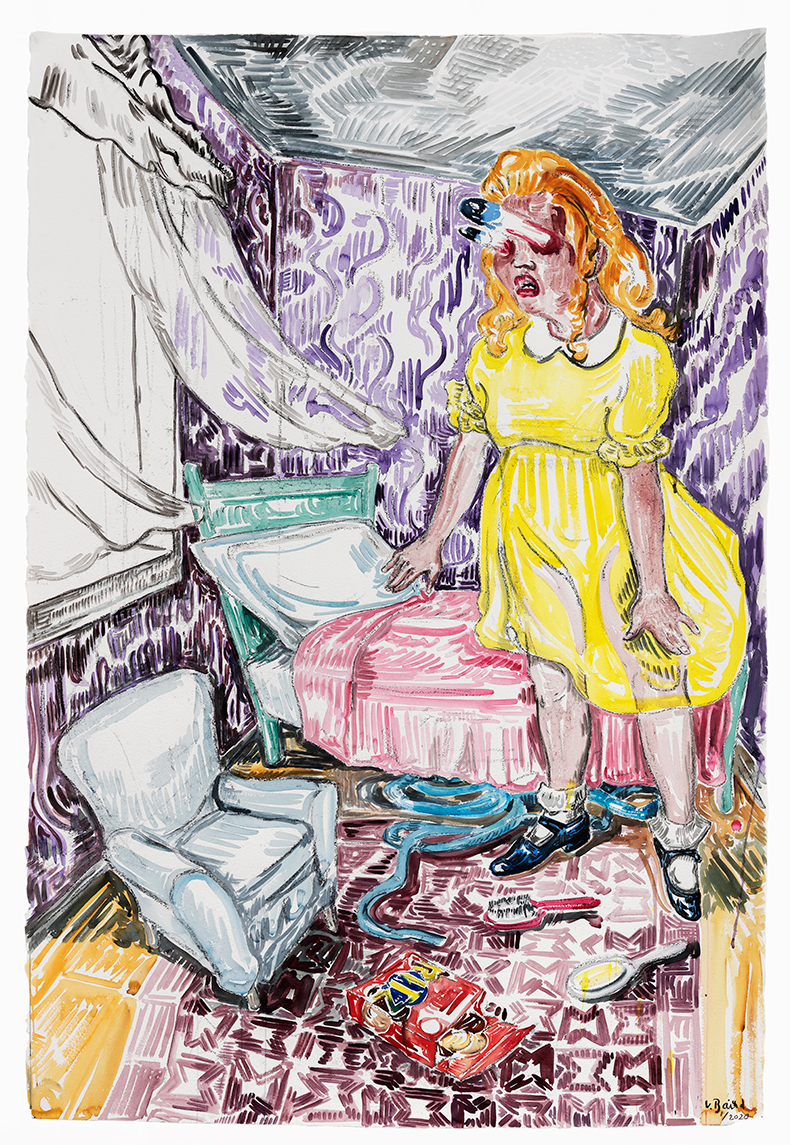

There are two recurring characters in Vanessa Baird’s exhibition of watercolour drawings at No. 9 Cork Street, London. One is a cross-looking, yellow-skinned, bony old woman, wearing nothing but soiled diapers. The other is a woman dressed in a Disney-style Snow White costume, complete with puffy blue sleeves, a canary-coloured skirt and white apron. Both are larger than life – huge, looming figures, cramped into the shadowy corners of a room. As the exhibition progresses, the power dynamic between them changes. In one scene, the elderly woman appears slumped and inert in a chair while the other stands beside her, arms raised in a gesture of empathy or, perhaps, helplessness. In another, Snow White is stripped of her costume and shrunken, clutched like a rag doll in the hands of a monstrous figure in a dressing gown who appears, mouth open, as if ready to gobble her whole. ‘That’s my mother,’ Baird explains. ‘I have made myself the hero, the Disney princess.’

Baird has been making drawings for the last 50 years. It’s a daily practice, a ritual – how she escapes reality but also makes sense of it, in what she calls ‘a senseless way’. Born to a Norwegian father and a Glaswegian mother who was also an artist, Baird was raised in Oslo, but travelled often to Scotland and always felt very much part of the culture there – a kinship that comes out through a lilt in her accent, as well as through her art (a solo exhibition of her drawings is also on display at the Glasgow Women’s Library until 28 January 2023). After her parents split up, it was her mother who became the main carer, Baird’s principal artistic influence and now, at the age of 92, her muse. ‘Sometimes I think maybe I’m continuing her project, but I have more self-confidence and it comes more easily to me,’ she says.

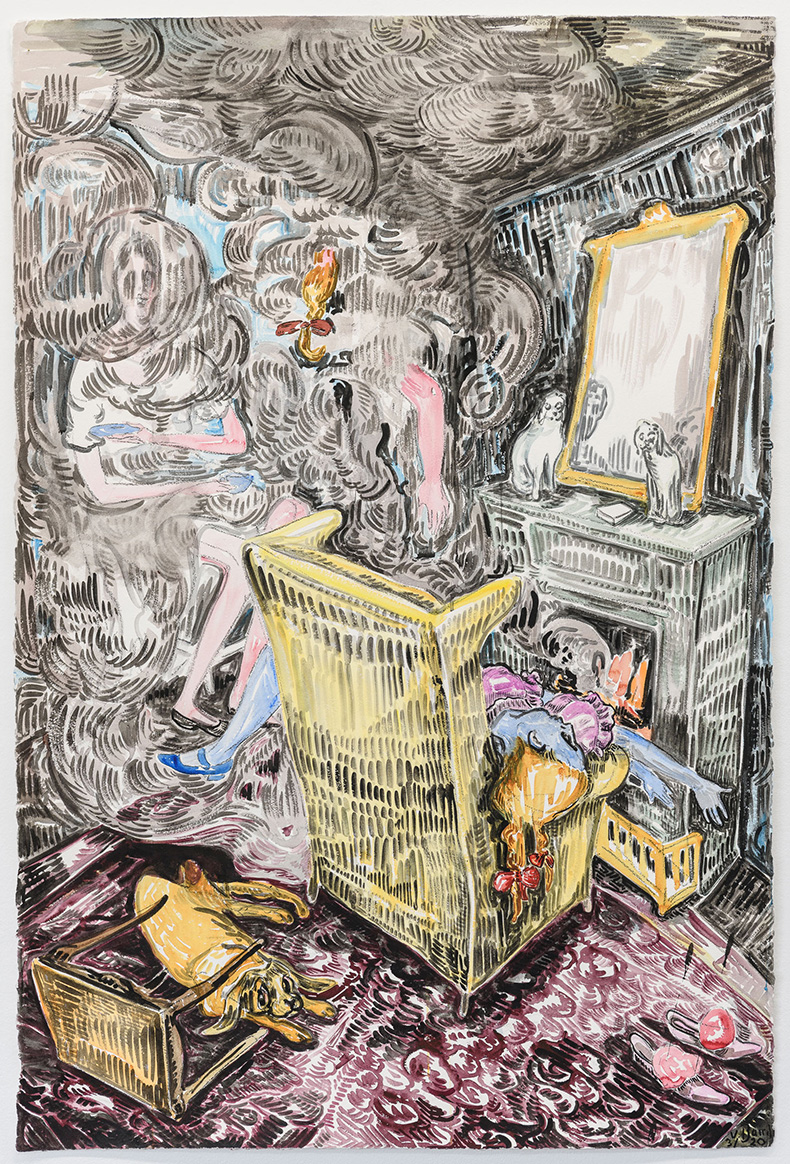

Untitled drawing from the series ‘I Can Get Right Down to the End of the Town and Be Back in Time for Tea’ (2020-2022), Vanessa Baird. Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen; courtesy artist and OSL contemporary

Baird was accepted into the Oslo National Academy of the Arts at the age of 17. There she briefly toyed with the idea of becoming a painter – ‘I couldn’t handle it, I became all stiff’ – before returning to what she knew best, but she wasn’t allowed to finish the year. ‘The bloke that was head of the school was religious you see, and I was making work that was explicit in subject matter,’ she explains. Fortunately, another of her tutors was more sympathetic and helped her to get an interview at the illustration department of the Royal College of Art in London, where she found herself studying under Quentin Blake. ‘He was lovely, very gentle and sophisticated. He organised lunches and had poets come in to read to us once a week. It felt very different to my experiences [of art school] in Norway,’ she says.

Baird has always had a contrarian streak. On returning to Norway, she and a friend staged several exhibitions for which they chopped up work by successful and ‘not so successful’ artists to create ‘really horrible’ collages, photographs and sculptures. Meanwhile, Baird’s drawings, replete with exposed genitals, horrifying acts of violence, lurid sexual references and crude jokes have consistently continued to subvert traditional perceptions of femininity, family and the home. Most of the works on show at No. 9 Cork Street are set within familiar domestic spaces – the bedroom, the living room – that are turned ghoulish by Baird’s swirling, watery brushstrokes. The home ‘is a nice set to make something really nasty happen,’ she says, with a sense of glee, pointing at a picture of a drawing room billowing with smoke in which her blonde and, in this instance, pig-tailed protagonist has turned blue and collapsed over an armchair, but it’s not all for dramatic effect.

Untitled drawing from the series ‘I Can Get Right Down to the End of the Town and Be Back in Time for Tea’ (2020-2022), Vanessa Baird. Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen; courtesy artist and OSL contemporary

Baird’s art-making, like many women’s, has for many years been made to fit around and within her role as a carer – a mother to three children, a guardian to her ex-partner who struggled with alcoholism and a nurse to her mother, who until recently lived with them. ‘Every morning when [my mother] was in our house, I would go to see what kind of condition she was in and I would film her, which is a very mean thing to do. She would be there in her diapers, going mental because she was psychotic. I thought maybe I’d make a film out of it with nice music, but I also might never do anything. The thing was to keep me doing the job, to make it interesting,’ says Baird.

On the one hand, it’s easy to imagine how drawing fairy tales gone awry – petticoats blown up, insects crawling over a bed, giant phalluses, eyeballs bursting from their sockets – might satisfy some impish impulse to blow things up, to cause a scene, but the fact that the horror plays out within a corner and in a world of semi-make-believe also points at an attempt to piece things together, to make sense of the swerving, surreal turns of everyday life. The show’s title (named after a series of drawings), ‘I Can Get Right Down to the End of the Town and Be Back in Time for Tea’ is, Baird tells me, ‘an assurance – something you say to your mother or partner when you leave the house’, just as the bright colours, jokes and slapstick drama reassure the viewer that however violent or nasty things might get, somehow it will all be okay in the end.

Untitled (2020), Vanessa Baird. Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen; courtesy artist and OSL contemporary

Hanging in the first room of the gallery, amid a wall plastered with drawings, is a series made in response to the war in Ukraine – the blue bodies of women and children lie scattered in pools of blood within sparse woodland settings. Stripped of kitsch costumes and taken out of the familiar interior setting, these works appear still and bare. ‘The terrifying thing [about the war] is that daily life doesn’t function anymore. People are going out and not coming back. It’s very difficult to understand something like that,’ says Baird. ‘When I get back [to Norway] I think I’ll have to keep tearing bodies apart.’

‘Vanessa Baird: I Can Get Back Down to the End of the Town and Be Back in Time for Tea’ is at No. 9 Cork Street, London until 26 November. Her work is also on show at the Glasgow Women’s Library until 28 January 2023.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

The threat to Sudan’s cultural heritage