‘If my paintings get to you, they do so before the sensible person has had time to draw any conclusion about them at all,’ Victor Willing said in 1986. Ten years earlier, sometime in 1976, he had found himself staring at the wall of his studio – a cold, bare and windowless room of a condemned school in Stepney. Act two of his remarkable, novelistic life had dealt a series of blows. Following the Carnation Revolution of 1974, his family lost their quinta in Ericeira, Portugal, and the enviable life it afforded them. The debilitating effects of multiple sclerosis, diagnosed ten years previously, had begun to make themselves known. What’s more, his dazzling promise as a painter appeared to have fizzled, blocked by his own fierce criticisms – and perhaps also by the productivity of his wife, the incomparable Paula Rego. He succumbed to what he called ‘a long daydream’, punctuated by an attempt to helm his father-in-law’s electronics firm. The ‘sensible person’ might not have advised that Willing, already hobbling, should now embark on canvases ‘a mile long’ (in Rego’s recollection). Thankfully for British art, he did exactly that.

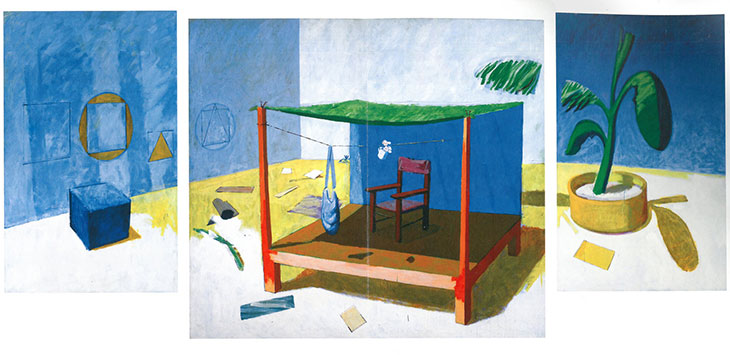

Place (triptych; 1976–78), Victor Willing. Courtesy the estate of Victor Willing and Marlborough Gallery, New York and London

The triptych Place (1976–78) appeared to him as a vision through three holes in that former classroom wall. The hallucinatory episodes he experienced around this time are often attributed to medication for MS, but this has in fact been discounted, and seems, rather, to have been the result of various intense pressures coming to bear: a psychosis, perhaps, but also a sudden clearing, delivering the images he needed. Francis Bacon, who had bought his hungry young friend Victor proper breakfasts, found his pictures ‘dropped in like slides’ – Willing’s came through the wall. And following the protracted caesura in his output, a powerful distillation had occurred, concentrating memories of his peripatetic Armed Forces childhood and the essentials of his knowledge – retaining a sureness and fluency from his Slade days but discarding the stifling self-censure. Thus Place channels the bright heat of the Alexandria of his boyhood and renders an entirely imagined scene of a camp shelter, apparently teleported into the studio, with vivid presence. It’s as if a sandstorm blasted through all the hesitation of the ‘sensible person’ and deposited ready-made enigmas for him to transcribe.

The division of the canvases is emphasised by the shift in background colours, from lilac-grey to blue, bisecting a green leaf as it crosses the mismatched panels – so languid fronds appear to stutter. Chairs and tables in Rien (1980) and Night (1978), like the frond in Place, are shown only partially, sheared off, in garbled perspective, or sinking into the ground. Perhaps these evoke the sense of a vision appearing or receding, but they are evidence, too, that dealing with the stranger demands of resolving a painting was second nature to Willing. These abbreviations and omissions are all geared toward the fluency and concision of his images. And they give his painting breath. Lucian Freud once refrained from completing the paisley motif on his mother’s pyjamas, realising it would be visual pedantry. In Willing’s painting, such economy is fundamental. Ethereal figures, meanwhile, appear in pastel drawings for Rien and Place, but seem to prove extraneous or untranslatable to the large paintings, where diffuse objects – a discarded suit, or cup, bag and chair – invoke a protagonist while avoiding the tethering effect of their presence.

Night (1978), Victor Willing. Pallant House Gallery, Chichester. © The estate of Victor Willing

When pressed by Rego, Willing responded that the apparent lack of finish in Place was to retain the feel of a drawing, and in a series of pastels upstairs, you recognise the challenge of not losing the breezy vitality of his studies – and measuring up to their ravishing beauty. Place with a Red Thing (1980) and Rien keep the drawings’ quavering borders, the sense of an image framed within a page. Scaled up, Willing’s forms have palpable, sculptural heft, and brim with pathos, but are made with a brisk, matter-of-fact, often feathered touch that gives them a feeling of buoyancy. Place with a Red Thing obliquely refers to Jonah and the Whale, with red tail flukes spryly poised in the midst of a kind of soft play area. With a minimum of fuss, his hovering brush knows when to thicken colour into something structural, and when to trail off into thin air. The few cursory, dragged strokes of King’s Blue in Rien, possibly indicating a blustery sky, are impossibly elegant. In Cart (1978) and Night, patches of hot orange and lavender are sown beneath creamier layers, creating warmth that shimmers through the surface, even when it occasionally builds to a porridge consistency.

Head of a Girl (Paula Rego) (1954), Victor Willing. Courtesy Hastings Contemporary; © Lens and Pixel

Place was ‘the best thing Vic ever did’, according to Paula Rego – and who would argue with that? The centrepiece of the ‘Victor Willing: Visions’ at Hastings Contemporary (until 5 January 2020), it would be worth the trip to the south coast alone. This is a substantial exhibition – satisfyingly thorough, and rich in his most indelible images. Of his earlier work, there is a portrait of the teenage Paula Rego, as delicately observed as a Gwen John, and nude studies freckled with the influence of William Coldstream’s method. A handful of paintings survive that anticipated the later idiom – Precarious Drag (1957) gauzily indistinct, shows something like a rucksack and hammock in the breeze, and Still Life with Model Boat (1957) something of his sculptural arranging of forms on a modest scale. With an illuminating new documentary by his film-maker son Nick Willing, plus an extensive new monograph, and a concurrent show at Turps Gallery in South London, it’s something of an early Christmas if this work already matters to you. Otherwise, it’s prime time to get acquainted. In the fresh tang of these seaside galleries, it retains the sense of revelation Nicholas Serota found, of an artist who seemed to ‘spring, fully formed, from nowhere’. These are consummate paintings, bristling with paradox, resolutely opaque, wafting a particular intensity.

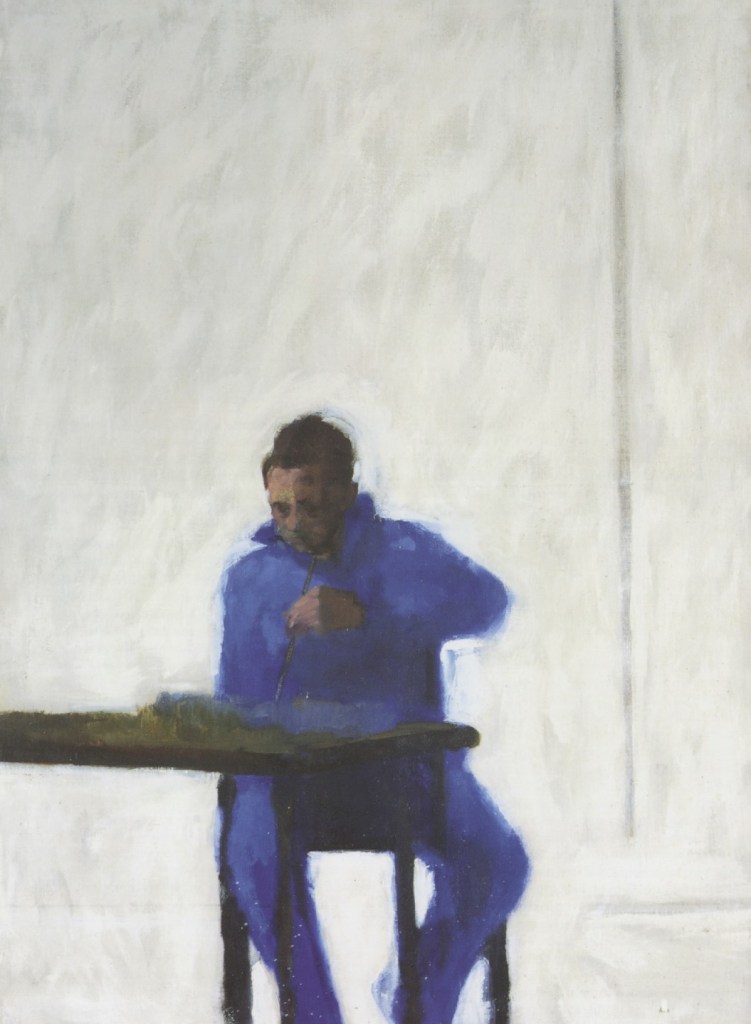

Self-portrait © The estate of Victor Willing

‘Victor Willing: Visions’ is at Hastings Contemporary until 5 January 2020.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)