From the July/August 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Back in the 1960s I discovered a tiny threadbare volume among my grandmother’s things called The Book of Ices (1885). Its author was Agnes Marshall, who ran a cookery school just north of Oxford Circus. To a greedy 13-year-old, Marshall’s ice-cream flavours sounded irresistible, but what appealed even more were the sumptuous chromolithograph illustrations of her frozen delights. I could not believe my eyes. There were trompe l’oeil ices in the form of courting doves, swans, cauliflowers, pineapples and a host of other glacial fantasies.

Ice cream in 1960s England was predominantly vanilla-flavoured, factory-made and served in a cone. My teenage brain started working overtime. How could Victorians have made ice cream without electrical freezers? And how did they conjure up these extraordinary ice-cream birds and hilarious joke vegetables? The numerous advertisements in Marshall’s book provided some answers. She was the inventor of a hand-cranked freezer, which she boasted could make a pint of perfectly frozen ice cream in five minutes, merely by rotating the ingredients in an ice and salt mixture. There were also dozens of steel engravings of ‘fancy pewter moulds’ in the form of life-sized cucumbers, hens on nests, melons, asparagus spears and giant strawberries. All could be purchased from her Mortimer Street cookery school, together with the necessary ingredients. But this establishment had closed before the Great War. I was now obsessed with a desire to make ice creams like this myself; but where could I find the required equipment?

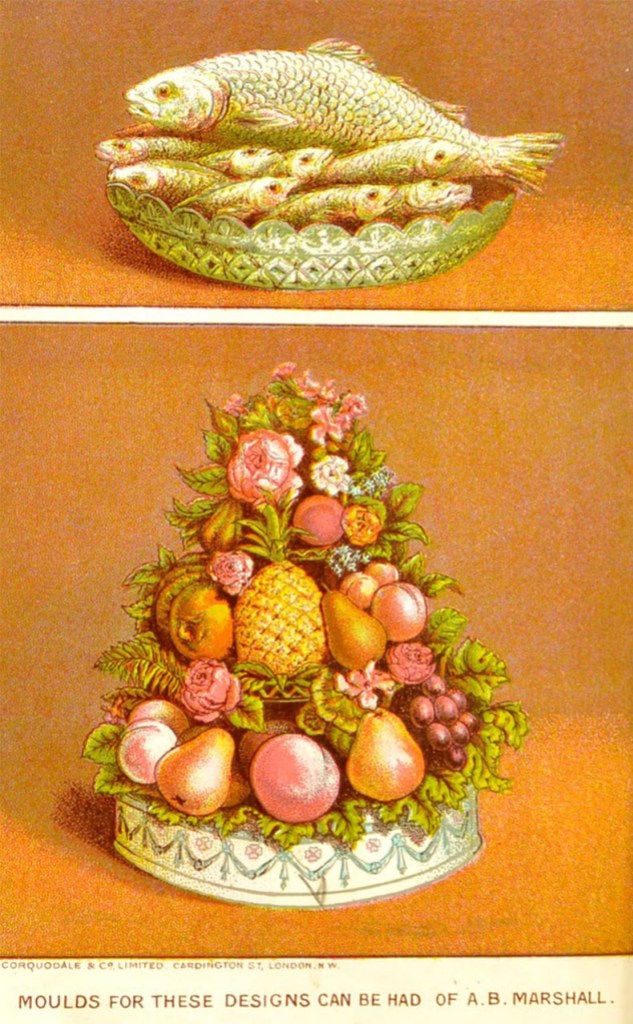

A page from The Book of Ices showing fish and fruit designs

I soon discovered that Marshall had written a second book called Fancy Ices (1894), which contained recipes for even more complicated creations. Among these was an ‘Ellen Terry Melon’, a realistic cantaloupe crafted from apple ice cream coloured red with Marshall’s own brand of carmine, but with an outer skin of melon water-ice flavoured with maraschino. The finished melon was served on a bed of meringue and garnished with a veil of spun sugar. On a visit to Portobello Road on my 18th birthday, I was delighted to buy not only one of Marshall’s freezers but also my first mould: a large, hinged pewter melon. With great difficulty I made my first ‘fancy ice’ and was astonished by its otherworldly beauty.

A medley of moulded ice creams made by Ivan Day according to recipes by Agnes Marshall. Photo: Ivan Day

Later research revealed that such stunning creations had been around for centuries, long before Marshall’s lifetime. An anonymous pamphlet of recipes published in Naples in the 1690s refers to ices called pezzi duri (hard pieces), frozen in similar pewter moulds. Pewter, an alloy of tin with copper and antimony or lead, does not corrode in a saline solution and is a very effective thermal conductor. The French cook Vincent La Chapelle was the first to explain how to use these moulds, in 1733, and may have introduced them to Britain. One of his contemporaries, the pewterer Thomas Chamberlain, was selling ‘all sorts of ice cream and sugar moulds’ from his premises in Greek Street, Soho, in the same decade. So these Neapolitan culinary caprices had probably arrived in England by the reign of George I, or even earlier. In 1751, spectacular illustrations of the moulds appeared in a book by Joseph Gilliers, head confectioner at the massive palace near Nancy of Stanislaw Leszczynski, the deposed king of Poland. Gilliers not only provided a recipe for parmesan ice cream, but also illustrated a mould to form it into a wedge of cheese. His other engravings depict ices in the form of truffles, crayfish and a large ham.

At first only the super-rich enjoyed these frozen fantasies. In the 1780s King Ferdinand IV of Naples and his queen Maria Carolina visited the convent complex of San Gregorio Armeno. The English traveller Dr John Moore happened to be at the convent for the occasion and he tells of a sumptuous meal the sisters prepared for the king and queen. Although the feast appeared to consist of a variety of meat and fish, all the dishes were moulded ice creams and water ices: ‘The Queen chose a slice of cold turkey, which, on being cut up, turned out a large piece of lemon ice, of the shape and appearance of a roasted turkey. All the other dishes were ices of various kinds, disguised under the forms of joints of meat; fish, and fowl.’

A basket of flowers made by Ivan Day from moulded water ices. Photo: Ivan Day

In the Victorian period, moulds celebrating recent inventions and important events became fashionable, including ices in the form of steam locomotives and Cleopatra’s Needle. There were anarchists’ bombs and champagne bottles, some even with separate ice-cream corks. Mrs Marshall continued this playful tradition into the early years of the 20th century, teaching the cooks of newly rich families in their suburban villas to make these icy novelties, which a hundred years earlier would have been relished only in a royal palace.

From the July/August 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)