From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Roy Strong’s book The Renaissance Garden in England (1979) was dedicated to the ‘memory of all those gardens destroyed by Capability Brown and his successors’. But the closest successor to those vanished Tudor landscapes, the Victorian garden with its formal parterres, balustrades and fountains, is all but lost too. Recent long-term restoration work by English Heritage is finally succeeding in recreating the former great splendour of the gardens of Witley Court in Worcestershire, but for decades its monumental Perseus and Andromeda fountain sat inoperable and forlorn, surveying mere lawns.

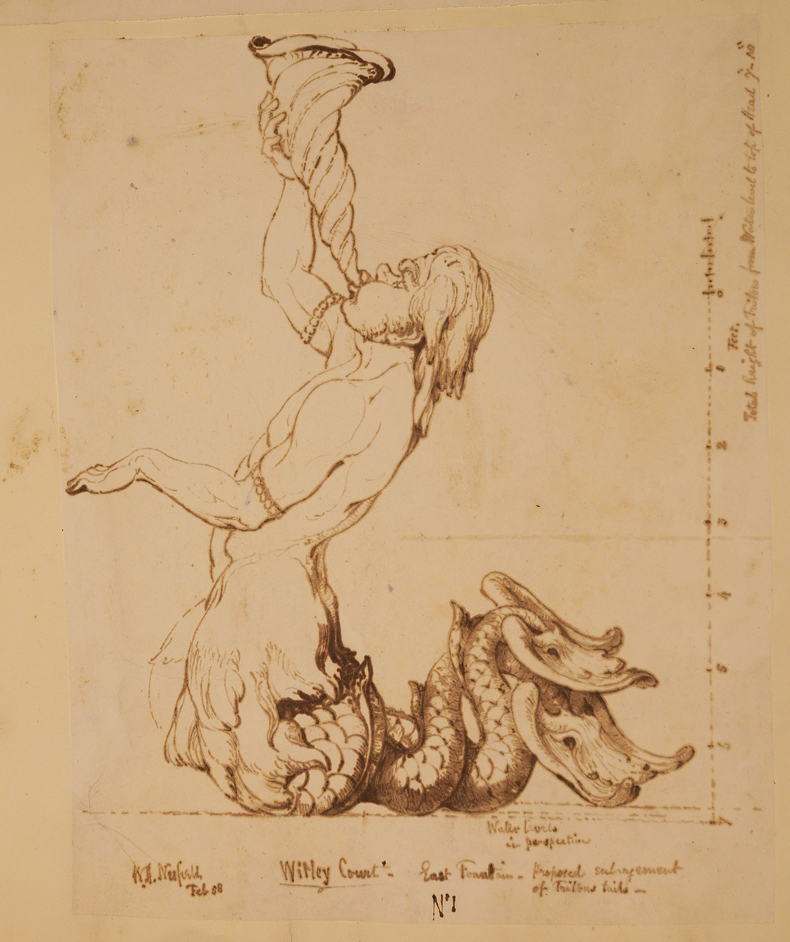

Study for Witley Court fountain (dated 1858) by William Andrews Nesfield. Image: Garden Museum, London

The fountain was the centrepiece of a design by the prolific landscape architect William Andrews Nesfield, a surname now more closely identified with his son the architect William Eden Nesfield, the partner and friend of Richard Norman Shaw. In a move that will in time re-establish his reputation, the Garden Museum has acquired Nesfield senior’s substantial archive, some 700 designs and plans as well as watercolours, sketches and notebooks. Nesfield dominated the Victorian horticultural scene for decades, with interventions in the major London parks as well as on private estates.

Study for Witley Court fountain by William Andrews Nesfield. Image: Garden Museum, London

He was born in County Durham in 1793; after serving as an officer in the Peninsular War, he defended Upper Canada from the American invasion of 1814. Resigning his commission in 1818 and picking up on an earlier interest that had been encouraged by his aunt, the Marchioness of Winchester, he took lessons in painting; he soon became accomplished in dramatic landscape scenes replete with cliffs and castles.

This was the 1820s, so he, along with many distinguished artist friends, visited the most picturesque of the rocky outcrops of Britain as well as the prettier parts of the Alps. He then returned to embark on a career which enabled him to convert his romantic landscapes into reality. This rapidly became possible because his cousin was Anthony Salvin, one of the most versatile of the generation of architects who survived the transition from amusing Regency eclecticism to the critically acceptable Gothic Revival. Nesfield and Salvin were close – they had once shared a house in Newman Street in London – and from the mid 1820s Salvin was working on the design of large country houses with landscaped estates. Nesfield seems to have helped with some of these, but in time he developed his own practice, devising the countless but now mostly vanished schemes that exemplify what people mean when they talk about Victorian formal gardens.

Some of Nesfield’s popular innovations are so long gone that it is hard to imagine what they were like. From early on his trademark was the parterre de broderie, a layout of colourful gravel bordered with low strips of box to resemble a pattern created in embroidery. These lay within geometrical outlines, with only a few isolated shrubs and statues rising to any height. Typically, borders of the garden as a whole would be defined with substantial balustrades, especially at look-out points, and fountains or conservatories. Variations of these were in full evidence in the largest of the schemes where he worked, which included the Regent’s Park broad walk and St James’s Park as well as on private estates such as Witley and Alton Towers. The architect J.M. Brydon later referred to him respectfully as ‘the major’ (he had actually risen as far as lieutenant) and noted that he had ‘a keen eye for architectural effects’; and there is a suggestion that he had a military manner that was well suited to organising great gardens, notably his facility with the axe. The later prominence in landscape history of the anti-Victorians, the Robinson-Jekyll school of clouds of irregular multi-coloured shrubbery, has pushed the reputation of a consummate master gardener like Nesfield into the shade.

Various parterre designs by William Andrews Nesfield. Image courtesy Garden Museum, London

Nesfield had developed his skill in the era of J.C. Loudon, the first great theorist of landscape architecture, and Loudon had been the first to promote his work. In his writing from the early century onwards Loudon had mirrored the positivist approach to the arts and sciences then emerging by seeing and writing about landscape design as if it was an entirely rational proposition. He launched himself with attacks on the picturesque ‘clumps’ of planting with which Humphry Repton and others had decorated the gardens of the great houses in imitation of Capability Brown; his own ideal landscape was the arboretum with its neat paths and instructive, organised trees and shrubs. And Loudon had condemned in particular the picturesque habit of hiding the business end of horticulture – the gardeners’ cottages, the sheds and the mounds – behind artistic planting; instead, the landowner should make these into attractive structures in their own right. This is the model that Nesfield drew on. Nothing in one of his gardens was anything other than what it looked like.

The Perseus and Andromeda fountain, designed in the 1850s by William Andrews Nesfield (1793–1881), at Witley Court, Great Witley. Photo: English Heritage

But a further, intriguing part of this story is the way in which Nesfield bequeathed to his son William Eden a disciplined sensitivity to rural settings and vernacular building. The two were very close and lived together for 30 years of the old man’s life – in a touching letter that recalled his father’s final moments, Nesfield junior described him as his ‘dear old Dad’. And William Eden launched his own career not only by assisting William Andrews with garden plans, but also by contributing the design of their memorably beautiful lodges. The best of these survives in Kew Gardens, on axis to the east with the Temperate House. Designed in 1866, this little red brick structure with its pilasters, tall roof and chimney and delicate ornament was the very first building of the revived ‘Queen Anne’ style, which in time Nesfield junior and Norman Shaw were to make famous as the precursor to the English free style. The Kew lodge assembled picturesque components of early houses, but it did it in a disciplined way that had both stylistic coherence and charm. And thus it was that the Nesfields between them forged the link between the world of George IV and the startling, beautiful houses that made late 19th-century British architecture famous around the world.

From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.