From the July/August 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

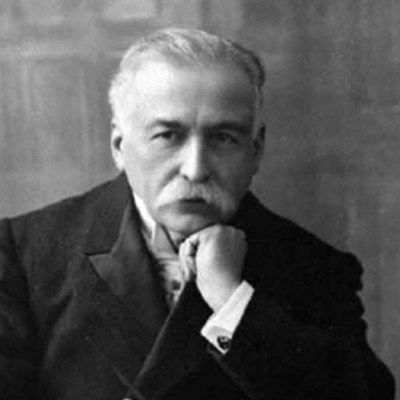

‘It is too little understood in England,’ wrote the art historian William Gaunt in 1927, ‘that the preparation of food is an art in itself.’ An exception was X. Marcel Boulestin (1878–1943), who had recently opened the Restaurant Boulestin near Covent Garden – a haven for the senses, as Gaunt described it, in which decoration enhanced dining in a manner quite new to London. The French dishes, whether classical or regional, were impeccably cooked; the yellow-silk curtains, with a print design by Raoul Dufy, ‘strictly eupeptic’.

Eighty years after his death, Boulestin is largely a forgotten figure. But during the 1920s and ’30s, his was a household name. His restaurant in the West End fed the great and the good, from Virginia Woolf to the Aga Khan, Lloyd George to Charlie Chaplin – and at prices as haughty as the clients themselves. But with his food journalism and cookery books, from Simple French Cooking for English Homes (1923) onwards, he reached an eager public in middle-class homes across Britain. In the early 1930s he published a primer on cooking eggs and another on potatoes.

Boulestin’s recipes and menus – unpretentious, often seasonal and mostly French – were not so much aspirational as achievable. He rarely specified quantities or cooking times, trusting his readers to make accommodation for the quality of their ingredients and equipment. ‘Do not be afraid to talk about food,’ he wrote. It was the easy, conversational tone of his writing, perhaps, that prompted first HMV to ask Boulestin to make gramophone records of his cookery lessons and then the Gas Company to engage him for a series of educational films, which were shown in cinemas around the country. In 1937 he became the first person to cook on television.

For Elizabeth David, X. Marcel Boulestin was a hero. She must have recognised something of herself in him, I think, when she wrote that he had helped to establish the kitchen ‘as part of the natural order of everyday living’. Boulestin had no professional training (he imported a chef from Paris to cook in his restaurant) and believed that ‘practically any dinner can be prepared easily with [a] few utensils’. He was ‘inspiriting and creative’, David wrote: ‘His special gift was to get us on the move.’

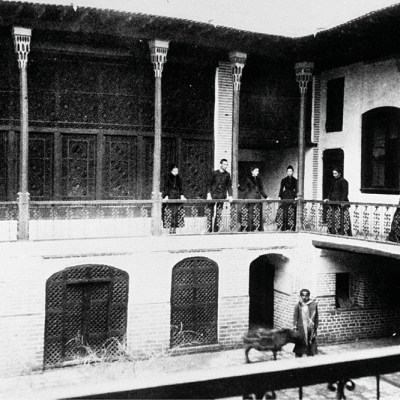

Part of the mural by Jean-Émile Laboureur (1877–1943) in Restaurant Boulestin in London. Photo: Print Collector/Getty Images

Boulestin’s knack for shaping taste, and his dedication to its practical application, had long been established before he became famous for food. Brought up in some affluence in Poitiers, he had drifted to Paris as a young music critic, becoming secretary to Colette’s husband Willy (Henry Gauthier-Villars). To read Boulestin’s autobiography Myself, My Two Countries (1936), is to encounter a Zelig-like figure of the fin de siècle, a spear carrier to the protagonists of both high culture and the avant-garde: he appeared on stage with Colette, took apéritifs with Walter Sickert at Dieppe, and translated a novella by Max Beerbohm, who returned the favour with a caricature.

It was in London, where Boulestin moved decisively in 1906, that he fully realised the persuasiveness of his own aesthetic judgement. Determining that ‘modern decoration was non-existent in England’, he set up shop in Elizabeth Street, Belgravia, in 1911, showing fabrics, wallpapers and objects in a domestic setting that would embolden patrons to emulate his example (a decade later, the precursor for his restaurant would be a supper club avant la lettre, run by Boulestin and his partner Robin Adair in their flat in London). ‘I had silks, linens, bibelots from Martine, André Groult and Iribe,’ he wrote, and ‘all sorts of unusual and amusing vases, china, glass from Paris.’

Decoration Moderne was one of the first dedicated interiors shops in London, its success marked not only through high takings but also in the model it provided early clients such as Syrie Wellcome (later Maugham) to later set up decorating businesses of their own. A second iteration of the shop after the First World War was less fruitful, with high-quality materials scarce and greater competition for customers besides. Boulestin chose to roll his sleeves up, as he later would to teach cookery. He put the business into liquidation and began making lampshades.

That he was both maker and tastemaker undoubtedly informed Boulestin’s openness to collaboration. In the Restaurant Boulestin that willingness found expression in the decoration by the designer André Groult, in the Dufy curtains, and in the mural paintings by Marie Laurencin and Jean Émile Laboureur, which transformed the restaurant’s anteroom into a modern Parisian circus. Cecil Beaton noted in his diary that it was ‘the prettiest restaurant in London’.

But Boulestin’s feeling for the aesthetic was never exclusionary or merely elitist. It extended to his books, many illustrated by his close friend Laboureur with energetic, cubism-inflected engravings. ‘It was uncommon in those days, and still is [in 1965], for publishers to commission artists of such quality to illustrate cookery books,’ noted David. Boulestin’s Herbs, Salads and Seasonings (1930; co-authored by Jason Hill) included 16 delicate line drawings by another friend, Cedric Morris: the forms of fennel, endive and pimentos established in white space, with no shading, through simple but decisive mark-making. In their way, these illustrations encapsulate Boulestin himself: more suggestive than prescriptive, refined but simple, and now too easily overlooked

From the July/August 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.