In The Young and Evil (1933), a novel by Parker Tyler and Charles Henri Ford, a loose plot drawn from the authors’ experience of the queer underground in depression-era New York is scrambled by modernist devices. Using experimental narrative techniques to describe cruising for sex around Times Square and the ball scene in Harlem, the book caused something of a stir; it was banned in Britain and the United States, praised by Gertrude Stein and is said to have been thrown into a fire by an appalled Edith Sitwell.

Tyler and Ford were part of a bohemian network of queer artists and writers based in New York around the middle of the 20th century whose work similarly blurred the lines between their artistic, social, and sexual lives. The Young and Evil: Queer Modernism in New York, 1930–1955, published this year by David Zwirner after an exhibition of the same name in 2019, sets out to map this milieu, which also included Ford’s partner, the Russian artist Pavel Tchelitchew; the painters Paul Cadmus, George Tooker and Margaret and Jared French; the photographer George Platt Lynes; the writer Glenway Wescott; as well as the publisher Monroe Wheeler and the impresario Lincoln Kirstein.

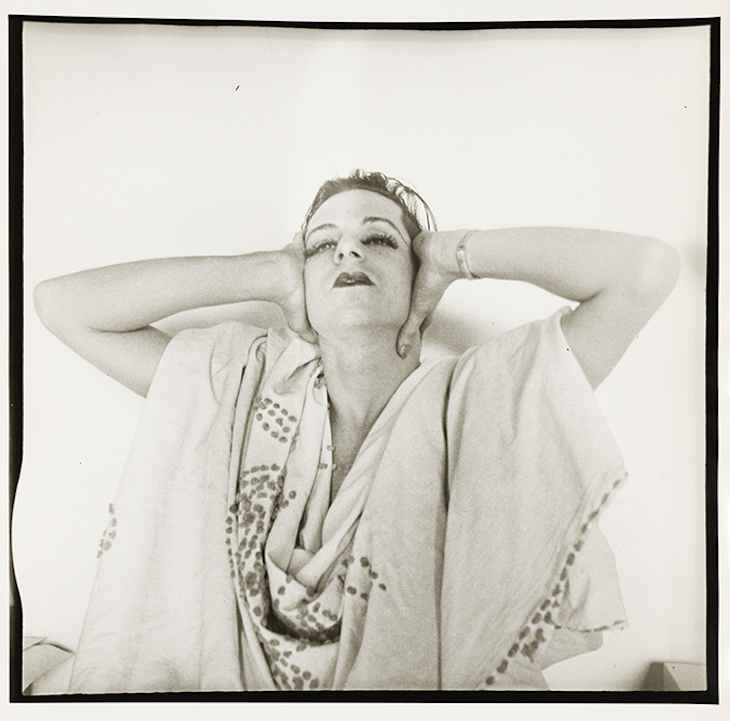

Parker Tyler in Drag (c. 1940–43), Charles Henri Ford

Presented as a kind of scrapbook, the book combines erotica produced by Pavel Tchelitchew and Paul Cadmus, and nude photographs by George Platt Lynes, with a family album of images made of and by the wider group. In his introduction, Jarrett Earnest describes how he explored the estates of these artists and their lovers, his attentions ‘dictated by the materials themselves’. It’s easy to see what interested him. One such search among the papers of Monroe Wheeler turned up a series of photographs taken by Lynes, who was one of his lovers, in the early 1930s. These soft-focus photos show Wheeler and Lynes in bed. In one, Wheeler’s penis is framed in close-up; in another it’s in Lynes’s mouth, and in a third they are face-to-face, posing with their eyes closed as if asleep in each other’s arms. Earnest draws a parallel between the survival of these snapshots and that of the homoerotic frescoes found on the walls of the Tomb of the Diver near Paestum in southern Italy, which, when they were unearthed in 1986, ‘jumped, as though by time travel, into the cultural consciousness of the late twentieth century’.

Histories of modernism in the mid 20th century have generally dismissed these artists and their work as passé when compared with the concurrent development of Abstract Expressionism. In the first of two essays in the book, however, the art historian Ann Reynolds describes how Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, and the magazine they edited, View, were at the centre of an alternative international avant-garde in New York around the time of the Second World War. Artists and writers from a ‘broad variety of literary, political, and artistic worlds’ were brought together on View’s strikingly designed pages, which at various times featured work by Marcel Duchamp and André Breton, and other Europeans riding out the war in New York, as well as North Americans such as Kirstein, Paul Bowles, Georgia O’Keeffe, Marshall McLuhan and Harold Rosenberg.

View published Parker Tyler’s essay ‘The Erotic Spectator’ (1944), in which he describes how works of art can alert viewers to the importance of their libido in their experience of reality. His understanding of the relationship between art and life was shared to some extent by his contemporaries; Reynolds argues that Tchelitchew, Lynes, and Cadmus, with their heightened and frequently erotic attention to the connection between bodies ‘on both sides of the picture plane’, aspired to a kind of image-making that ‘refashioned the world while recording it at the same time’.

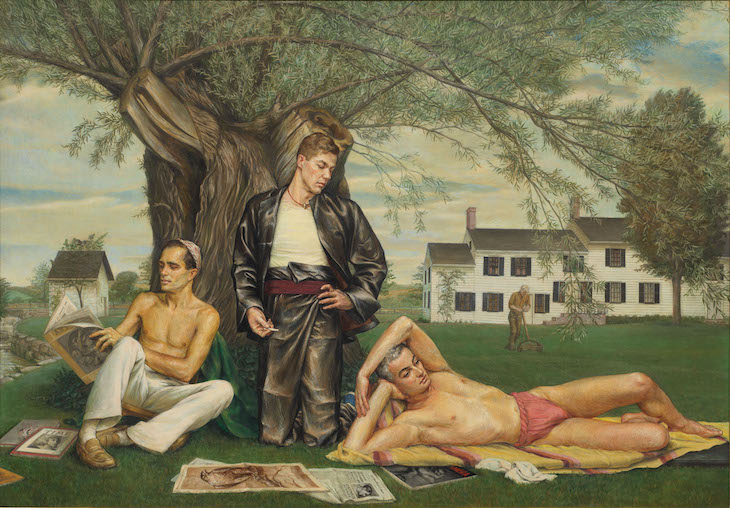

While The Young and Evil assembles an archive full of what art historian Kenneth E. Silver describes as the ecstatic ‘sucking and fucking’ of these artists’ erotica, the authors say little about the ways in which they depicted each other. Given that the majority of the works reproduced in the book function to varying degrees as portraits, this seems like a missed opportunity. Take, for example, the playful photographs shot by Cadmus and Jared and Margaret French, under their collective name PaJaMa. Though they operate on the one hand as holiday snapshots of their artist-friends, posing for the camera on the beaches of Fire Island and Provincetown, these highly choreographed images are also experiments with the dynamics of looking and being looked at. In Cadmus’s painting Stone Blossom (1939–40), another ménage à trois – Wheeler, Wescott and Lynes – lounge on the lawn in front of the eponymous country home they shared in New Jersey. In its queering of the 18th-century conversation piece genre, Stone Blossom epitomises the way in which these artists reimagined their own intertwined lives.

Stone Blossom: A Conversation Piece (1939–40), Paul Cadmus. © 2020 Estate of Paul Cadmus/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

The highly associative and intimate collection of images published in The Young and Evil provides a glimpse into the world of these queer moderns – a ‘picture of a crowd’ as Glenway Wescott described one of his own books in 1949. An elusive group of artists is given shape by the paintings, photographs and publications they made – works that are centred on the body, saturated with eroticism, and deserve further investigation.

The Young and Evil: Queer Modernism in New York, 1930–1955 by Jarrett Earnest (ed.) is published by David Zwirner Books.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)