From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

May’s auctions of 20th and 21st century art at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips in New York will be the biggest test of the art market so far this year. Last May nearly $2bn-worth of Impressionist, modern and contemporary art was sold in the city in just nine days.

The auction houses spent April busily promoting their star lots. These include a painting by Francis Bacon of his lover George Dyer, Portrait of George Dyer Crouching (1966; estimate $30m–$50m), at Sotheby’s, which was last seen in public in the Royal Academy’s exhibition ‘Francis Bacon: Man and Beast’ in 2022. Shortly after, Sotheby’s also announced the sale of a rare painting by Leonora Carrington, Les Distractions de Dagobert (1945; estimate $12m-$50m), a collaboration between Warhol and Basquiat and four paintings by Joan Mitchell.

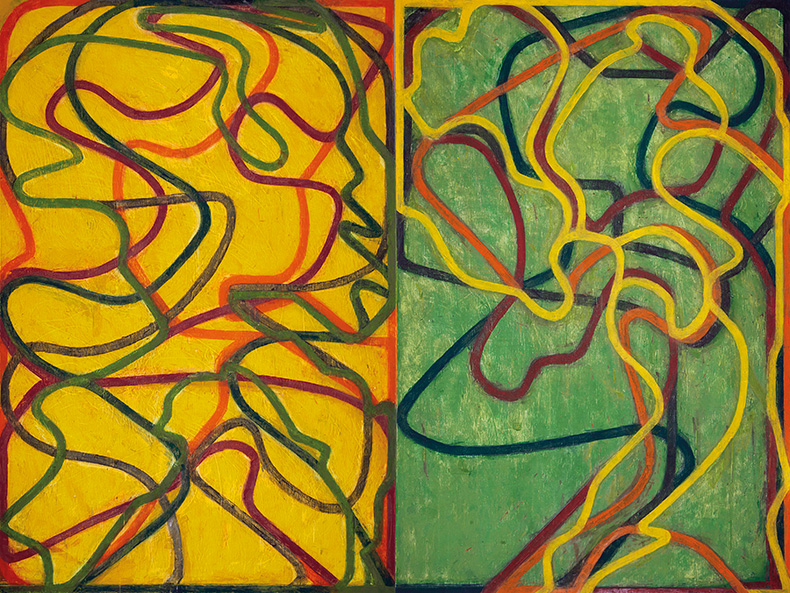

Christie’s has opted for a shimmering Monet riverscape, Moulin de Limetz (1888; estimate $18m–$25m) and a calligraphic Brice Marden diptych, Event (2004–07; estimate $30m–$50m) to lead its 20th and 21st-century sales respectively. The Marden is a late work, rather than one from the artist’s more famous minimalist period in the 1960s and ’70s, but a similar painting, Complements (2004–07), sold for $31m in 2020 – a record for a work by Marden.

Event (2004–07), Brice Marden. Photo: Christie’s Images Ltd, 2024

Phillips, meanwhile, is selling two paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (ELMAR) (1982; estimate $40m–$60m) and Untitled (Portrait of a Famous Ballplayer) (1981; estimate $6.5m–$8.5m). They were bought by Francesco Pellizzi, first husband of the co-founder of Dia Art Foundation Philippa de Menil, from Basquiat’s art dealer Annina Nosei in the early 1980s.

Despite the enthusiasm these works may drum up, other signs are less encouraging. Reports from art fairs earlier this year, including Frieze Los Angeles, TEFAF Maastricht and Art Basel Hong Kong, have been mixed at best.

A clearer, more verifiable picture has begun to emerge from international auctions in the first three months of the year. Fine art and luxury sales at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips are down by more than 18 per cent compared with the same period in 2023 – which in turn were almost 15 per cent lower than in 2022.

The most important of these sales – the Impressionist, modern and contemporary evening and day auctions in London in March – were down by 13 per cent overall. (Christie’s, it should be noted, bucked the overall trend. Seizing market share from the other two houses, its sales in London were up by almost 15 per cent.)

The art market bounced back in 2022 after two moribund years of lockdowns, leading some to predict a ‘new Roaring Twenties’. The political, military and economic crises of 2023 put a stop to that, but hopes were growing that an improving economic outlook would mean a healthier market in 2024. London’s sales were considered a bellwether, so a total of £372m (with fees) compared with £429m in 2023 and £549m in 2022 was something of a disappointment. The gloom deepened with Sotheby’s ‘The Now’ and modern and contemporary auctions in Hong Kong last month, which came in at £79m, down by more than 50 per cent from 2023 and under their low pre-sale estimates.

In May 2022 the New York auctions made $2.8bn, dropping to $1.8bn in May 2023. Any uplift this month will be seized upon by the art market with enthusiasm, even more so should totals exceed the $2.3bn made in the second big round of sales in November 2023. But what exactly should we be looking out for at this month’s New York auctions?

High-price lots

What is needed to boost the market are ‘important, unique, rare works of art’, says Philip Hoffman, founder of the art advisory and fund manager the Fine Art Group. ‘People will pay huge amounts of money for the very rarest – at least at the same level as two years ago or maybe even more.’ The difficulty is reassuring owners that now is a good time to sell.

In 2022 six works of art sold at auction for more than $100m each, the most expensive of which was Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (1964), which sold for $195m at Christie’s New York in May. Meanwhile, Magritte’s L’Empire des lumières (1951) sold for £59.4m at Sotheby’s in London that March. None of the works announced so far for New York have estimates close to these sums. In London, the number of lots hammering down at more than £1m was 58 in March 2024 compared with 71 in March 2022.

‘A lot of the froth has gone out of the market,’ Hoffman says. ‘Anything that’s B+ is probably selling at 20 per cent less than a year or two ago. The issue with London was that nothing terribly important came up and a lot of it just made the low estimate.’ At the London evening sales, two-thirds of works sold below their mid estimate and a quarter under the low estimate.

Portrait of George Dyer Crouching (1966), Francis Bacon. Photo: © Sotheby’s

Fewer withdrawals

Another sign to watch out for in New York will be the number of works withdrawn before, or even during, the sales. Laura Paulson, director of Gagosian Art Advisory and former global chairman of Christie’s, says that early in her career lot withdrawals were rare. It was ‘a worst-case scenario’ – a dispute over provenance or authenticity, for example – ‘but not because there was no interest’. This has started to change. As long ago as 2017 reporters started noticing big withdrawals – Egon Schiele’s Danaë (1909; estimate $30m–$40m) at Sotheby’s in May that year, is a case in point. The main reason for the uptick in withdrawals, as an art advisor told Artsy reporter Isaac Kaplan, was that a public failure to sell can be ‘damaging in the short term’ to its resale value.

Withdrawn works, unlike works that are offered but don’t sell, are struck from the public record. A total of 20 works (out of 191) were withdrawn from the marquee evening sales at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips in London in March, including paintings by George Condo, Wade Guyton and Francis Bacon. The auction houses are reluctant to discuss the reasons for the high number of withdrawals, but the consensus in the market is that pre-sale research indicated a lack of bidders for the works – at least at a price the consignor would accept.

‘We are very serious about trying to withdraw as little as possible,’ says Giovanna Bertazzoni, vice-chairman of 20th and 21st century art at Christie’s. ‘If an auction is a fair representation of the market and you start withdrawing, you are obfuscating the reality of things.’ But, she adds, auction houses have to protect their consignors. ‘A work of art is not like selling a plot of land or a car. It has a lot of emotional elements and at some point the owners may feel very naked, that it’s not the right time to sell any more.’

‘The issue is with consignors at the moment,’ Hoffman says. ‘Asia is holding back and European collectors are saying now is not a great time because interest rates are high. We’ve also got uncertainty in the Middle East – many important buyers and sellers, particularly with connections to Israel, are focused elsewhere.’

Major single-owner sales

At the time of writing no major single-owner sales have been announced for New York in May – bar the consignment of art owned by the late Miami collector Rosa de la Cruz (rumoured to be valued around $30m) and works of art owned by the late Iowa philanthropists John and Mary Pappajohn, both being sold at Christie’s.

‘What excites the market is when you have art from a David Solinger [former president of the Whitney Museum of American Art] or a Paul Allen collection: works that present rare opportunities,’ Paulson says. ‘We just haven’t yet seen something that is so extraordinarily blue-chip and fresh that it will tempt many of the major buyers that have emerged in the past 10 or 15 years,’ she told us early last month.

Untitled (ELMAR) (1982), Jean-Michel Basquiat. Courtesy Phillips

Fewer guarantees

When big collections do turn up, the lots are often guaranteed – a practice that has spread across the wider auction market. This is when a third party agrees to buy the work from the consignor for a pre-arranged minimum sum. If this isn’t reached by other bidders, the guarantor will take the work. But if the work does well, the guarantor and consignor will share the difference between the guarantee price and the final hammer price.

In a rising market consignors often do much better without guarantees, but the risk-averse often still take them. Guarantors, meanwhile, stand to make greater rewards as prices rise. In a weaker market, guarantees give consignors security but, unless they really want to keep the work, the position for guarantors is riskier. The fact that each deal is bespoke and private makes understanding guarantees a complicated process.

Anders Petterson, founder of art market analyst ArtTactic, says that the number of lots carrying guarantees can rise as the market weakens. But the total amount of money put down in guarantees follows the overall market trajectory. So, in 2022 total guarantees reached an estimated $3.7bn, or a high of 65 per cent of the value of the major marquee auctions based on low estimates. This dropped to 63 per cent in 2023 and, by the first quarter of 2024, to 58 per cent of the low value.

Petterson says that following guarantees offers a useful insight into the mood of the art trade. ‘If you are giving a guarantee, you have got to be able to understand and manage the risk, and you have got to be able to value the work. You have to know its worth, who might bid on it and where and how you might sell it,’ he says. ‘It means you have to be in the game. You might want to acquire the work [for resale] but you might also see the financing side as a good business opportunity.’ But returns are diminishing – Petterson estimates that these have dropped on average from a high of more than 20 per cent at the end of 2020 to around 6 per cent now – which suggests that the amount of money guarantors are prepared to risk is declining.

Either way, Paulson believes that guarantees are skewing the wider art market. In the major sales in New York in November 2008, no works were protected by a guarantee. In London in March this year 57 of the 134 works of art offered in the evening sales carried them. ‘There were so many works that had third-party guarantees [at what I believe] is full price, so we basically had a private sale in public,’ she says. ‘It means it doesn’t feel like a market.’ An art dealer who asked not to be named described the 31-lot, fully guaranteed sale of the art collector and Whitney Museum patron Emily Fisher Landau in November in New York, which was full of blue-chip works, as ‘boring’.

However this month’s New York auctions turn out, they are unlikely to be dismissed as dull. Experts say that there are still many wealthy buyers for good material. There are even hopes that increased activity in the lower price levels of the art market and the auction houses’ expansion into luxury goods may aid the emergence of new buyers. Sebastian Fahey, managing director of global fine art at Sotheby’s, says that in 2023 the auction house made a record $2.2bn on luxury and collectibles – which includes cars, baseball jerseys and sneakers – and that 28 per cent of these buyers also collect fine art.

But unless something changes radically between now and the sales themselves, it looks as though things will be much like the first three months of 2024. Far from disastrous, as it was in 2009 after the financial crash, but hardly full of the joys of spring.

Jane Morris is an independent editor, writer and commentator.

All data in this article was prepared for Apollo by art market research/analysts ArtTactic, unless otherwise stated.

From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)