Apollo’s regular insight into art market trends and highlights. Visit Apollo Collector Services for expert advice on navigating the art market.

It has been years since such a beautiful, scholarly dealer’s catalogue landed on my desk, and a century since any serious study addressed its subject. ‘Maiolica before Raphael’ (at Sam Fogg, London, from 8 May–16 June) features over 40 examples of late medieval and early Renaissance ceramics made in Italy from around 1275 to 1500 and uses its eponymous catalogue to set them in context – not least through the glorious paintings of both Italian and northern masters which represent them in ‘contemporary’ settings. In the 1470s, for instance, Antonello da Messina places the learned St Jerome in his study with maiolica bowls as plant pots, a pharmacy jar – albarello – and bottle on his bookshelves, and a whole floor of maiolica tiles below.

Inkstand with figures of the Virtues (c. 1480–90), probably Faenza. Courtesy Sam Fogg

While there has been a recent flurry of books on istoriato – the refined and elaborate maiolica wares decorated with biblical, historical and mythological scenes that began to be produced in Faenza after 1500 – these ‘primitive’ early wares have long remained unsung, even though at various periods they were more highly valued. It was in the 1870s that they began to be admired, just as ‘primitive’ painting had captured the imagination of Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites in England and the Nazarenes in Germany. In a sense, they are a painter’s pottery, and it comes as no surprise to discover that the first collectors in Britain were artists – William Holman-Hunt, Charles Fairfax Murray and Henry Wallis.

These bowls and vessels may seem rustic now but they were far from humble. The tin that came to be added to traditional lead glaze to create maiolica’s impermeable glassy white ground was imported from Cornwall, the cobalt blue from Persia. It is fascinating to see how the potters and painters working in Faenza, Pesaro, Deruta and beyond drew their inspiration not only from the costly Hispano-Moresque lustrewares imported from Valencia (the city’s copper lustre glaze was a closely guarded secret) but also from classical prototypes, Islamic metalwork, and Chinese porcelain. They were to fuse all of these formal and decorative influences to create a vocabulary of ornament and a rich palette of colour that were entirely new. An extended repertoire of vessels evolved in response to new social rituals of feasting.

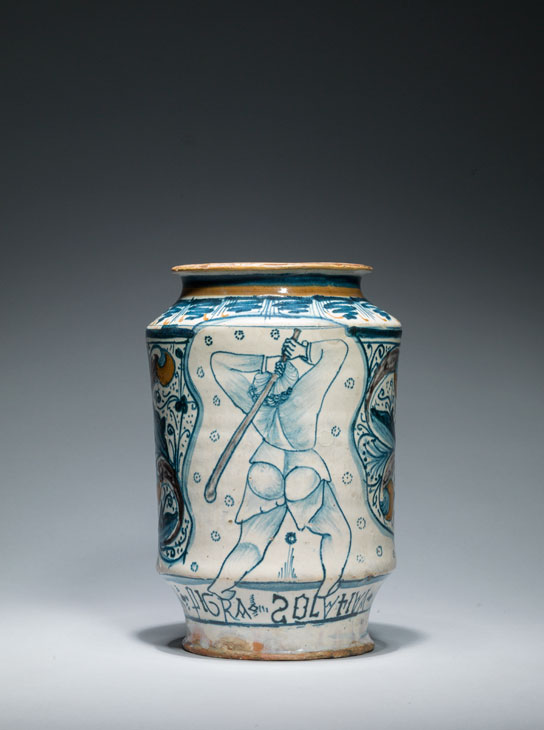

An albarello with man seen from behind. Courtesy Sam Fogg

Early maiolica has it all – even humour. An albarello here, made as its inscription reveals for the storage of purgatives, is ornamented by a man seen from behind and baring his bottom. This may be a business of mass production, but the particularity of some of these portraits suggests that they are specific likenesses. Similarly, the extraordinarily ambitious inkwell modelled with figures of the Virtues appears not to have been made using stock models. There is also a glorious, painterly – almost abstract – abandon in the splashes of cobalt and copper green in the palmettes and berries of an exceedingly rare and early tricolore jug of around 1420–40. These artisans showed considerable sophistication in their application of decoration to bulbous forms, but most of all it is the humanity that delights – the flourishes and thumb marks, the pooling of the glazes, or where the potter has punched out the cavity for a spout.

Unlike their counterparts in fresco, panel or canvas, these paintings on ceramics are as fresh today as they were when they left the workshop, even if the vessels are slightly worse for wear. Recent archaeological evidence has prompted new attributions to half the exhibits in this show, which was five years in the making, and one piece is hitherto unpublished. Prices range from £10,000–£100,000.

A three-colour jug showing a half-length figure in profile. (c. 1420–40), Florentine district, Montelupo or Bacchereto. Courtesy Sam Fogg

‘Maiolica Before Raphael’ is at Sam Fogg, London, from 8 May–16 June 2017.

Visit Apollo Collector Services for the best information and advice about managing an art collection.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)