Frieze London and the auctions that were scheduled to coincide with the fair revealed two contradictory directions for the art market last week. The fair was, undeniably, full of buzz and excitement. While it was busy, it didn’t have the manic over-crowded feel that certain collectors complained of in 2022. It seems that works were sold – Gagosian had pre-sold their entire stand of Damien Hirst’s flower pictures; the Tate snapped up an Andrew Cranston painting from Ingleby gallery – and private collectors seemed to be engaging with the artworks seriously.

For all the buzz in Regent’s Park, the auctions told a different story. Sotheby’s was the first auction house to hold its sales. As is becoming normal for the house, it separated its offer into more contemporary works gathered under the banner of the Now sale and a more traditional offering in their Contemporary sale. I suppose nomenclature becomes tricky when you’re set on indicating your relevance but have already used up the most present term available when categorising art.

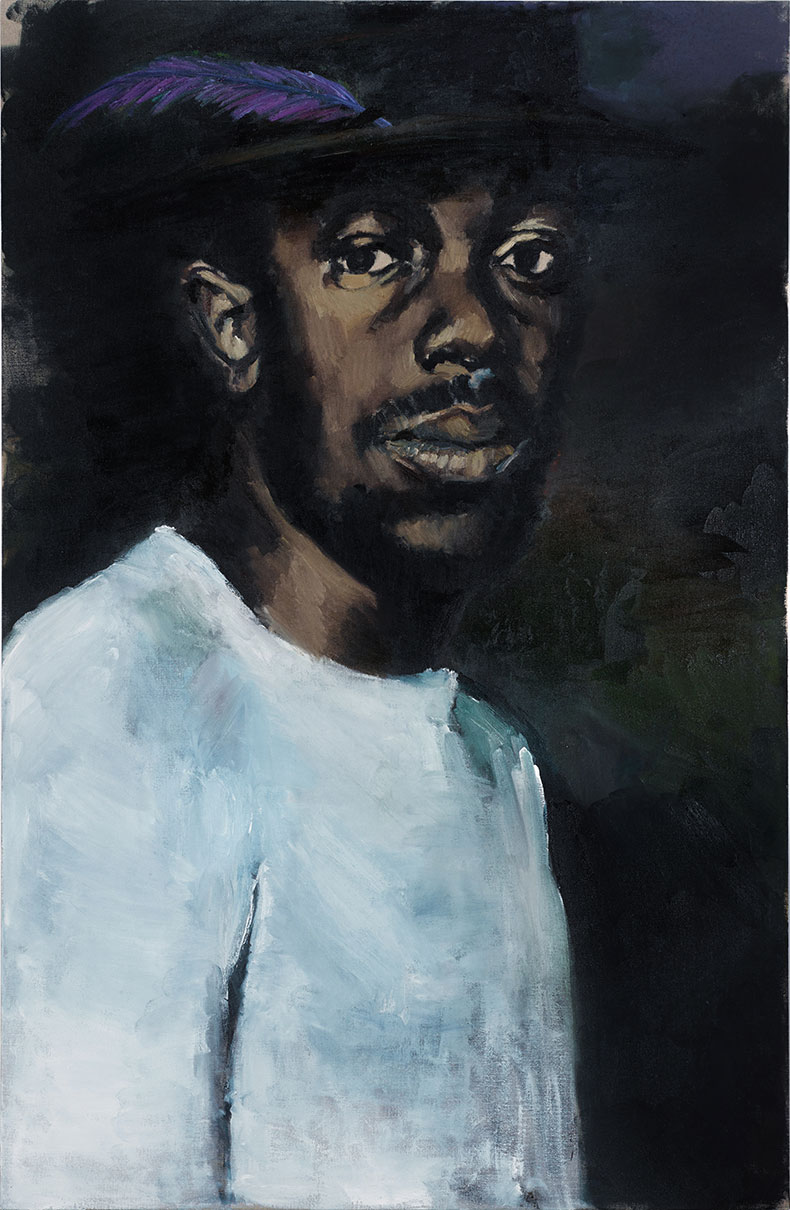

Six Birds in the Bush (2015), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Sotheby’s London, £2.95m

The Now sale was only 21 lots and had some successes. These included Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Six Birds in the Bush (2015), which sold for £2.95m against an estimate of £1.2m–£1.8m (estimates do not include fees, results do) and Cecily Brown’s Tricky (2001), which fetched £2.5m, also against an estimate of £1.2m–£1.8m. (Is the £2m to £3m bracket becoming the sweet spot for the London auction market?). Despite these works selling for well over their estimates, it was impossible to see what followed as anything other than a damp squib.

A spate of withdrawals saw the already small sale significantly reduced – but the greatest blow to Sotheby’s was the failure to sell Gerhard Richter’s Abstraktes Bild (1986), which had been estimated at £16m–£24m. The Now and Contemporary sales made a combined £45.6m: less than half of the £97.1m they managed to bring in this time last year.

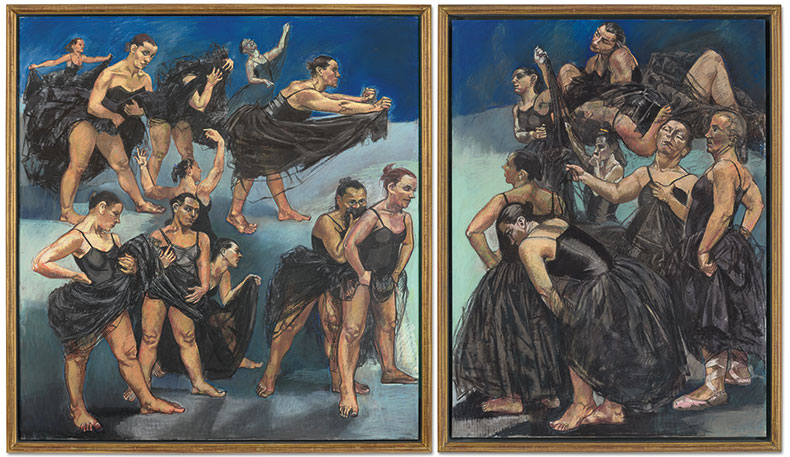

Dancing Ostriches from Walt Disney’s ‘Fantasia’ (1995), Paula Rego. Christie’s London, £3.1m.

Christie’s results tell a different story – but only slightly. Unlike its rival, the auction house did not try to capitalise on London’s reputation for cutting-edge art and, instead, presented a 20th/21st century auction, which included a Lucio Fontana among works by more contemporary artists such as Alvaro Barrington and Caroline Walker. The big successes of the evening were Paula Rego’s Dancing Ostriches from Walt Disney’s ‘Fantasia’ (1993) which realised a firmly mid-estimate £3.1m (that sweet spot again?) and Peter Doig’s House of Pictures (Haus der Bilder) (2000-02), which also came in plumply mid-estimate at £6.1m. The sale totalled £47.9m with 52 lots.

La Quiétude (1918), Kees van Dongen. Christie’s London, £10.8m

What buoyed the Christie’s results was the first part of the Sam Josefowitz collection (a name, perhaps, familiar to readers of Apollo, as his son was the magazine’s publisher). Josefowitz is renowned as one of the leading collectors of his generation. He assembled one of the great collections that ranged from Assyrian antiquities to exemplary Impressionist and Modern paintings. The first in a series of auctions dedicated to the collection made a total of £51.8m, with Kees van Dongen’s La Quiétude (1918) fetching £10.8m – over double its estimate of £3–£5m. This was enough to make Christie’s total appear a great deal more impressive than Sotheby’s, even though single-owner collections are not reliable indicators of the auction market, appearing irregularly and adding a lustre to lots that might otherwise not perform so well (though this was absolutely not the case with the Josefowitz collection).

At the same time that Frieze was making a big noise about all the collectors coming to London, the luxury conglomerate LVMH – whose presence at Frieze London through their champagne brand Ruinart is not exactly invisible, and who share many clients with Frieze – announced a slowing in their sales. Their shares dropped by seven per cent. The group which, like the auction houses, has relied on Chinese buyers to plug the gap when the US and European markets slumped, can no longer do this. The sale of the Long Collection at Sotheby’s Hong Kong suggests the same is true for auction houses. It was always assumed that while the air was thin at the top of the market, there were enough players internationally to keep it inflated. Against a background of geo-political uncertainty and economic difficulty it is becoming more apparent that there are fewer rich people anywhere in the world who are able to, or want to, sustain the market. The correction that so many people have been expecting is finally here. The question is whether the auction houses can manage things so as not to scare everyone off, or whether there’s going to be a panic that sees their supply dry up and perpetuate the bad atmosphere.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)