From the November 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I plan compulsively, feverishly. Everything from the structure of my books to my holiday packing. Is this a necessary quality, acquired as a working parent, or was I like this before? Perhaps. (I can no longer remember the before.) Sometimes, reading books with free-flowing structures and a flirtation with chaos, I envy the liberty – the confidence – to follow ideas as they loop and unfurl. To pursue the journey of words without a map.

I, the coward writer, work out of sight, in the discreet domain of the page. How much more nerve does it take to court chance on the open terrain of a large canvas?

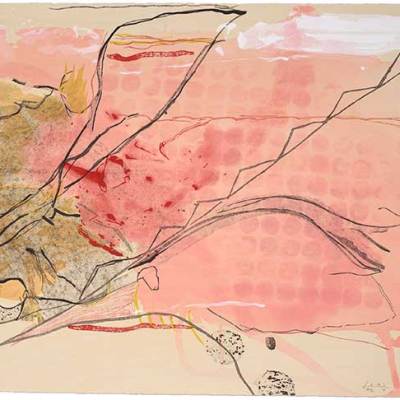

There’s a curatorial truism about the Abstract Expressionist Helen Frankenthaler: that she is an artist of whom a comprehensive survey is impossible. Each work takes up so much room that no museum would be large enough. She worked at a grand scale – habitually, three or four metres, often more – and the paintings themselves demand space in return. They will not be crowded. ‘Helen Frankenthaler: Painting Without Rules’ at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence nevertheless shows breadth, including sculpture, and sorties into gelatinous impasto in the 1980s. Across decades of experimentation and evolution, Frankenthaler returned regularly to the use of thinned paint, poured on to and soaking into the canvas.

Madrid (1984) is a concrete grey landscape stained with a river of puce in its foreground and a horizon formed from a lake of woodland green. Over these stains Frankenthaler incised graphic lines and loops in white, and a thick fleshy swipe of pink at the lower margin. In Tutti-Frutti (1966), great tongues of rich liquid colour plunge towards one another from opposite edges of the canvas – ultramarine, dusty mauve, yolk and tangerine – shimmering and tingeing at their edges but stopping just shy of flooding into one another. In the exquisite restraint of Driving East (2002), a thin strip of black hovers beneath a flooded sky of dark grey, revealing the barest hint of a pale blue understain as they meet: a flat nightscape viewed in the first stirrings toward dawn.

Helen Frankenthaler painting in her studio on East 83rd Street, New York, in 1964, with Fire on the floor and Small’s Paradise hanging on the wall. Photo: Alexander Liberman; © J. Paul Getty Trust (Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles); © 2024 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Frankenthaler painted on the floor (look closely and you will sometimes see a footprint). Thinking about the loose and unruly volume of that thinned acrylic paint puddling above the saturated canvas, I am moved by the courage required to make those first great pours, to tease colours ever closer toward their neighbours, to hold faith that a painting will emerge from the improvisation. Image was not required but, equally, Frankenthaler did not shy from the pictorial associations of a specific landscape, or season or time of day. Water, the night sky and the banded desert are carried within her paint.

Marlene Dumas has likewise courted chance, working with floods of thinned oils as first gestures towards the paintings in ‘Mourning Marsyas’ at Frith Street Gallery in London (until 16 November). Unlike Frankenthaler, Dumas deals in images, and the route from stain to painting involves the artist searching for the germs of form in her puddles and seeps. The show and its title work – in which streaks of sombre colour form tormented figures on a towering canvas – evoke the story of the satyr Marsyas. In the Metamorphoses, Ovid briefly tells of Marsyas’s audacity in playing his flute to rival Apollo’s lyre, of the satyr losing in musical competition against the god, and the cruel display of power that results, as he is flayed alive. This short passage is dominated by description not of the competition, but of pain – Marsyas’s ‘whole body […] a flaming wound’ – and the great lamentation that followed his death. When the satyr died, his music died with him. The lamentation was for the loss of that beauty as well as the horror of his death. Marsyas’s tale is a story of art and tyranny but also of bodies and their liquidity. Tears for Marsyas fell and stained the Earth in such volume that they pooled in deep caves and re-emerged as a fountain of clear water.

Utøya (2018–23), Marlene Dumas. Photo: Peter Cox; courtesy Marlene Dumas/Frith Street Gallery, London; © Marlene Dumas

Dumas’s paintings are dark and elegiac. The Widow (2021–24) towers, her liquid form dressed in weeds of thick shining oil paint, black on black, drowned in a veiling blue like the light of Frankenthaler’s dawn. In the same mournful palette, Utøya (2018–23) puddles with oily liquid. Thin stains and washes of palest grey create a watery illumination, like moonlight on sea, yet the moon in the painting is a black orb in a charcoal sky, and the reflection it casts on the water is inky. Utøya is a Norwegian island north-west of Oslo, its name now synonymous with a domestic terror attack in 2011 during which far-right extremist Anders Breivik opened fire at a summer camp. Like a photographic negative or solar eclipse, this black orb above the painted sea is ‘wrong’ – the world has been turned inside out.

Elsewhere, the stains lead Dumas towards a pair of bruising phalluses, each solid as a rubber cosh (Two Gods, 2021); a shaded face dissolving into smoke (Last Man Standing, 2023); and a smeared orange demon (The devil may care, 2024). As she examines her pours of paint like an augur, the horrors of our present moment manifest: violence, grief and cocksure bellicosity. In this fluid, improvised endeavour, Dumas’s role is less that of the bold Marsyas than of the Earth herself: to enact a metamorphosis and draw a clear fountain out from the muddied mass of tears.

From the November 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.