From the September 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Champagne is the only wine that leaves a woman beautiful after drinking it,’ Madame de Pompadour once declared. She would know, having – equally legendarily – lent her breast as a mould for the lead crystal shallow coupe, which has titillated connoisseurs for over three centuries.

As is the fate of many royal mistresses, she was both reviled for her power and admired for her taste. Intoxicating the court with her wit and champagne-drinking habit, she took an interest in art, philosophy and interiors. Among her passions was an unending collection of Vincennes (later known as Sèvres) porcelain that helped propel the house to become one of the greatest ceramic producers in history, with a surprising connection for the wine drinker.

Rosalind Savill’s recent book Everyday Rococo (see February 2022 issue of Apollo) details many of Mme de Pompadour’s purchases during her 19 years at court, between 1745 and 1764. Among these were specially commissioned porcelain wine labels – her vinicultural innovation – to clearly identify what was in the bottles (up to that point there was no way to tell what was distilled from barrels). The design was shield-shaped, with gilded grapes and holes for a silk string to tie the labels onto bottle necks. Six of these Sèvres wine labels can be found in the Ashmolean museum. Pompadour was also a keen enthusiast of new contemporary winery Moët et Cie (est. 1743), becoming its most loyal and highest spending client, reinforcing the breast mould story. One of her suppers at the Hôtel de Ville saw 1,800 bottles of champagne drunk.

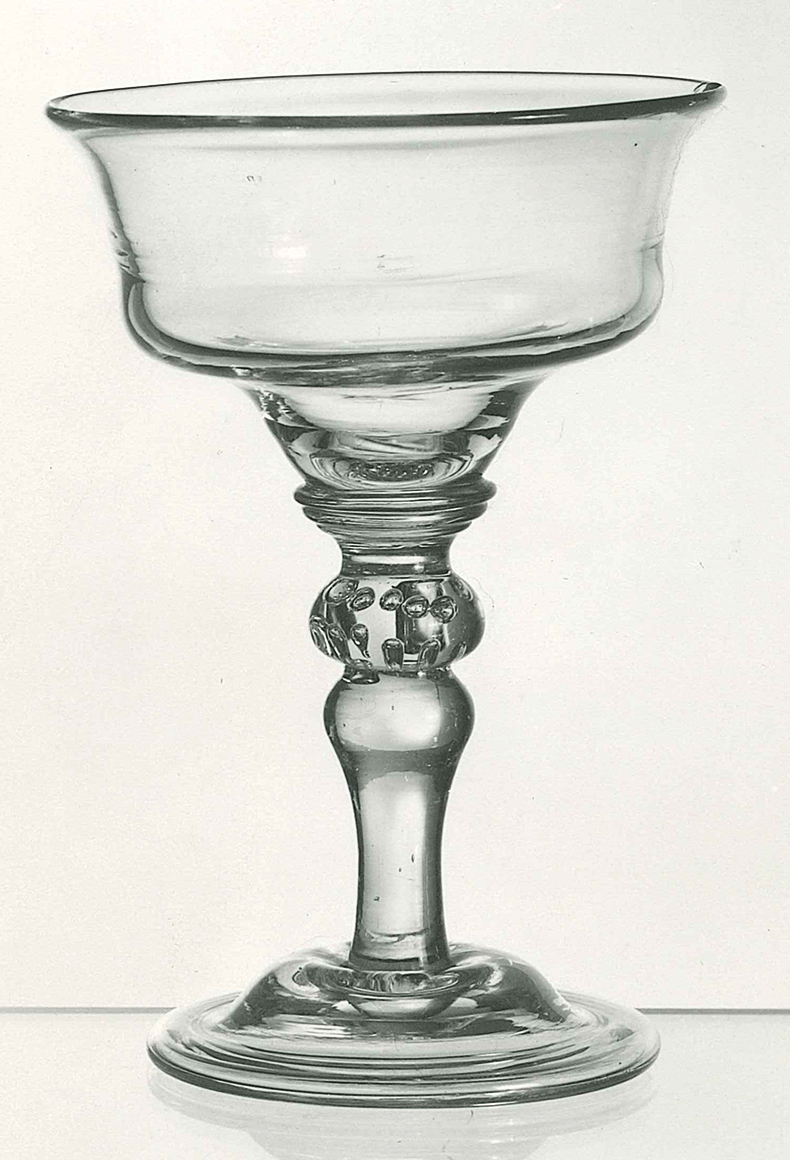

The coupe glass is said to have been modelled on the breast of Madame de Pompadour. Photo: courtesy Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio

So far, so good for creation myths. Sourcing exact origins of innovations related to viniculture are notoriously difficult – there are arguments that even ‘champagne’ was invented in England in the mid 17th century as ‘sparkling wine’ before France saw their first fermented bubble. A series of cold winters helped carbon ferment better, and initially, French tastes rejected mousseux wines as the bubbles were seen as a fault, whereas the English welcomed the effervescence.

But it seems that any maîtresse en titre worth her silks – and indeed her royal patronage – had to have a coupe glass attributed to her mammary throughout history. Long before Pompadour, a similar legend had been attributed to Diane de Poitiers (1499–1566), courtesan at the French court and the favourite of Henry II. It is said that she commissioned the royal glassblower of the Château d’Anet to make the glassware for the king to fulfil his stated fantasy: ‘To drink wine from her breasts.’

Marie Antoinette also had champagne glasses moulded in the shape of her left breast for all the court to toast to her good health. The glassware has not survived, but another drink- ing vessel which is variation on the same theme, the jatte-tétton (breast bowl) was designed by Jean-Jacques Lagreneé to honour the queen’s bosom. These jatte-tétons are now in the Musée National de Céramique de Sèvres in Paris.

Never one to miss out on stamping his foot on history, Napoleon is also said to have commissioned breast-shaped saucers based on Empress Joséphine’s body. More recently, in 2008, Karl Lagerfeld designed a coupe based on his muse Claudia Schiffer’s chest to celebrate the launch of Dom Pérignon 1995 vintage. And, in 2014, London restaurant 34 commissioned artist Jane McAdam Freud to design coupes based on the breasts of Kate Moss.

The allure of drinking from a breast- shaped cup predates any sparkling wine; mastos cups have been in existence since the 4th century BC in Greece. These ceramic conical-shaped vessels with handles and a nipple at the base were decorated with red-figure scenes of vines and celebrations. They were deployed in symposia and temple rites and held a ritualistic function in the worship of Demeter and Dionysus.

The Oyster Dinner (1735), Jean-François de Troy

The development of the coupe’s saucer shape is also tied to our changing tastes in how we drink wine, as well as status. Originally the round, shallow shape meant the drink would be knocked back, enhancing champagne’s reputation for excess. Court painter Jean-François de Troy’s The Oyster Dinner (1735) – the first work of art to feature a bottle of champagne – was commissioned by Louis XV for his private dining room. In it you can see noblemen enjoying a banquet while guzzling from coupes. Originally this glass shape was reserved for the nobility (the clergy drank cava in Bordeaux glasses). Early modern drinkers of sparkling wine did not care for strong bubbles, so the larger surface space allowed the bubbles to evaporate (even though this is not technically a concern when it comes to good quality vintage champagne).

By the late 1930s the shallow glass was no longer desirable as tastes shifted to welcome more effervescence. By this time the flute had become the preferred glass shape, allowing the carbon bubbles to rise towards the narrower surface level. Today, oenophiles have replaced the flute with the tulip for the appreciation of complex champagnes, as it combines a wider surface for extracting aromas, but tapers to preserve the carbonation of the wine.

The multiple legends that tell and retell how the coupe was modelled on a famous breast have just as many corresponding myth-busters. Given the frivolity and joy of drinking champagne, nobody wants to be scolded or denigrated if they choose to believe these stories, and there is certainly a breast (myth) for every type of drinker.

From the September 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze